Can Humanity Master Technology?

One of the great questions of our age is whether or not we as human beings will be able to master technology or will we continue to be mastered by it? Essentially, it is a moral question.

Technology. It is a difficult argument today to try and convince ourselves that we as human beings are still masters of our tools, machines and technology. Our lives are so shaped and governed by technology, and more importantly, by technical thinking, that we can scarcely see the fullness of its influence all around us. We are like fish swimming in water and do not realize we are wet.

There is no denying that there is immense power in the technical. It lays at the foundation of much of our lives today. It is integral to science, medicine, manufacturing, communications, transportation, administration and more. Many of us feel trapped by technology, but we know that letting go of technology means letting go of its power. It is not by accident that Tolkien wove our relationship to technology into his story about middle earth, tying it to the ring of power.

I have often used the analogy that the knowledge of technique and the technical are very much like the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil whose fruit was forbidden us by God. It is not by accident that city building and the use of tools was ascribed to the line of Cain. After Cain kills his brother, the main genealogy of Adam continues through their third son, Seth. Because of his crimes, Cain lives more deeply under the judgement of God. It is through this line that technology is introduced. Why raise this point? There is this interesting admonition from God that precedes Cain’s murder of his brother Abel:

“Why are you distressed,

And why is your face fallen?

Surely if you do right,

There is uplift.

But if you do not do right

Sin crouches at the door;

Its urge is towards you,

Yet you can be its master."

Translation from JPS Torah CommentaryAm I suggesting that the use of technology and technique are a form of sin and evil? No. But, that said, there is an aspect to technique, in that once it crosses a certain, point it has a devouring effect. There is that line, once transgressed, where the technical takes over our lives, our thinking and actions. It becomes our master.

The lure of technology is intense. Its main offerings are power and control, and through them the promise of money and a better life. The serpent tantalized Eve with offerings of wisdom and knowledge. Technology seduces us with the lure of power and control. The power to harness nature, unleashing and directing its energies. We are told that this will all be for the improvement and betterment of mankind. Better health, prosperity, the curing of social ills. Technique gives us the power to save mankind from itself. This is the promise of “progress.”

Technology also makes the implied promise that whatever problems come as a result of its implementation, they can be addressed by more technical progress. All through the 1990’s and 2000’s this was the message from the right against the left when it came to environmental problems. We don’t need to control or limit our market activity, our consumption, or change our lifestyle in any way. Science and technology will provide the solutions if we simply get out of the way and allow the marketplace to work. Innovation and technology will find a solution for us because there is money to be made in cleaning up the environment. This narrative gets applied again and again across the technical landscape. Your kids are watching porn on the computer you bought them? Buy content management software to control what they see. This software will empower you as a parent.

Much of our thinking on technology filters through two lenses. The first is that of progress. This is the bias towards what is new and novel over what is old, tried and true. “New and improved” has more cache than “proven and reliable.” There are plenty of people who make careers out of being change managers, but few can do the same being tradition curators. It is also a mindset which approaches the world with the attitude that we must always be “moving forward” by making small incremental changes that we believe are improvements over how we currently do things. Old is backwards. New is progress.

The second is that of philosophical materialism. Technology, like the universe, is just matter, just a thing. It has no inherent meaning or content of its own. As a result, there is this belief that technology is “neutral,” that is neither good nor bad. It obtains its moral quality from us, its users. If we use technique for good, then it is good. If we use it for evil, it will be evil. There is nothing inherent in the techniques themselves that make them good or bad. Its all in the way you use them.

Jacques Ellul has a very different understanding of technique. He argues that they are neither good nor bad, but rather, they are ambivalent. Techniques and technology simply do not care. The very use of them will have effects whether you want those effects or not. From this, Ellul develops four “laws” of technology and technique.

First, all technical progress has its price.

In other words, there is a cost to using technique and technology. You cannot opt out from paying the price when you use a technology. Every technique—plan method, system—every technology—machine, device, tool—will have positives, that is, good things that come from its implementation; and it will also have negatives, that is, bad or evil things that come as a result of its use. There is no escaping this two fold nature of technique. All technology has its positives and its negatives, its good and its bad. The technology does not care. When you use it, you will get both.

Second, at each stage it raises more and greater problems than it solves.

Every time you use technology and technique to solve a problem—usually one generated in the first place by technique—there will be positives for sure, but you will generate more problems than you solved. Those problems will grow with each new layer of technology. They will grow in number and complexity along a curve that is exponential. As society becomes more technically sophisticated, so too will its problems grow in direct relationship to the level of complexity.

Third, its harmful effects are inseparable from its beneficial effects.

This states more boldly and expands upon the first point. Bad effects will come from the use of every technology. There is nothing you can do in terms of design or planning to prevent the negative effects from coming because they are directly tied to the benefits you receive from its implementation.

Fourth, it has a great number of unforeseen effects.

Not only can you not gain benefits from technology without the accompanying harms, there are a whole lot of both good and bad effects that you cannot account for in advance. There is no amount of planning or testing that will reveal all of the effects of a technique, both good and bad.

So what does this mean for us in our relationship with technology? The long and short of it is this: the only way to adequately avoid the evils of any one technique or technology is to not use it or to stop using it once its evils reveal themselves. Because any attempt to fix the evils of one technique with more technique, or a different technique or a new technique will generate its own evils—at a greater rate than the technology it is intended to replace or fix—we have to recognize that a solution to technology will not come from within the technical system itself.

This creates an imperative upon us as human beings to master our use of the technical. We have to assert moral control over technology by choosing to not use it in the first place—the risks being too great—or to stop using it once implemented and its negative effects become apparent and the price paid becomes too high. Far too often, almost never, are we willing to give up the power and control that technology provides. In this sense, Tolkien saw more clearly than most that the ring of power cannot be wielded, it must be destroyed.

Does this demand some Butlerian Jihad? A Luddite rebellion? Perhaps. But probably not. Technology, like sin, is urging itself toward us, but we must master it. But what it does mean is that we place technology within clear boundaries. Like how the virtue of chastity, both outside and inside marriage, are intended to grapple with the powerful energies of human sexuality, so too we need a kind of technical chastity to deal with “the machine.” Is this likely? Probably not, at least not at this moment. But we need to begin the discussion of our relationship to the technical. We are helped greatly when our eyes are opened and we are able to see the world truly. It gives us opportunities to do things differently, to walk a different path when we can. Perhaps we can make a kind of peace with the technical, a form of stasis in which we know the benefits and the harms of the technologies we choose to use, and are comfortable with both the benefit gained and the price to be paid. That would be far better than running constantly pell mell into new, greater and more complex ills with every new technology, regardless of its perceived benefits.

Technique as Ideology

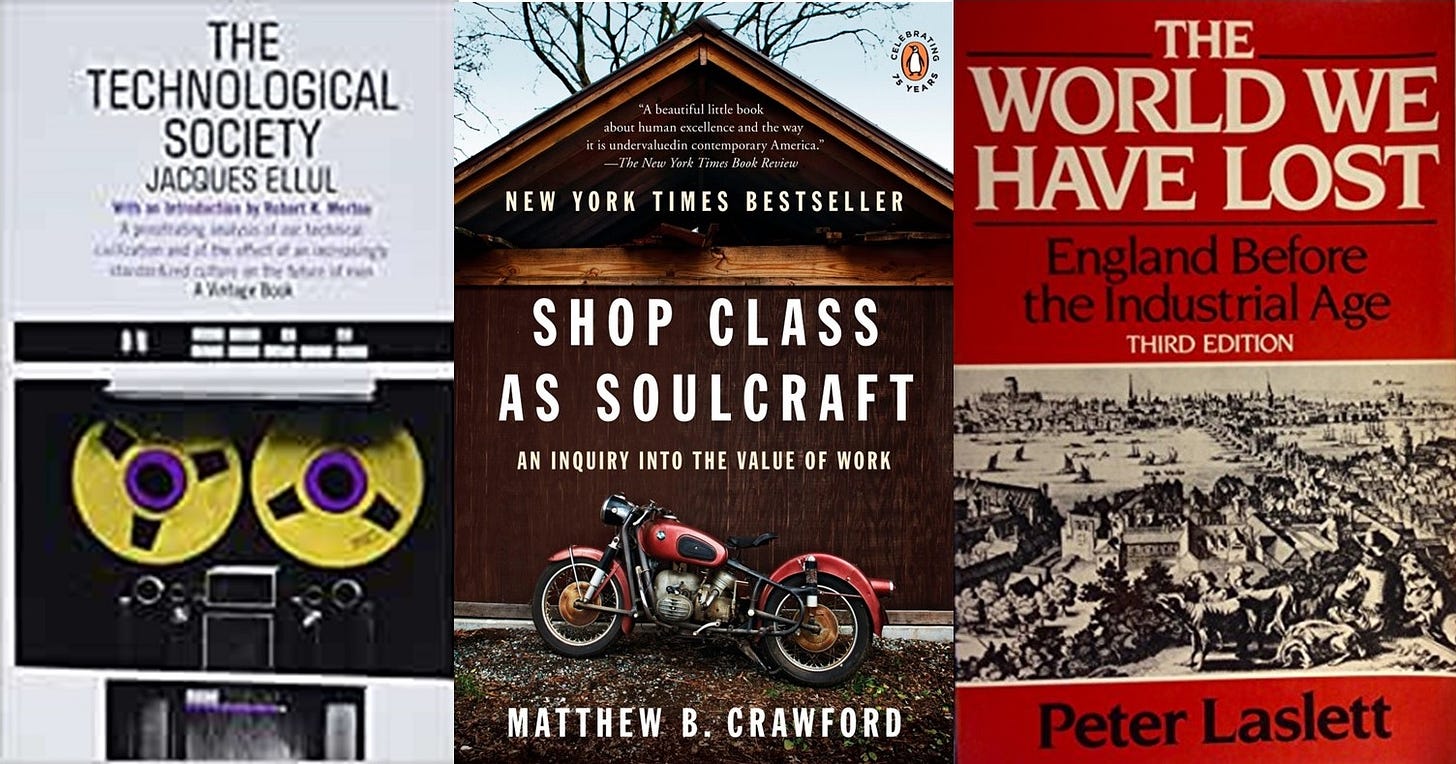

There is a lot of confusion about technology, the technical and technique. While devices and machines will always be an important part of the technical, far more important is the mindset and patterns of thinking that it engenders. Technology creates a technical mindset. Matthew Crawford, in his book “Shop Class as Soul Craft” talks about this technical mindset as applied to work in today’s world. Every task, no matter how rich in imbedded knowledge and personal skill, is taken apart, broken down and its essential bits are pulled out and transformed into an efficient, repeatable, rational process that can be applied to multiple contexts and is largely invariant in regards to the person. You can train anyone in this distilled method and you will be able to produce consistent repeatable results. All the depth and richness of a task, all the creativity and personal uniqueness applied to it is stripped away and it is transformed into a detailed process, a system, something machine like and ripe for automation. It is efficient, repeatable, productive, cost effective and quality controlled. There is tremendous power in this process. But there is no need for human creativity or an intelligent, engaged relationship to one’s work.

Technique is the way of thinking in which every problem has but one overarching solution, the technical approach. In this regard, technique elevates itself to a kind of ideology. It is as utopian as ideologies like Marxism or Fascism. It is the operating system upon which the managerial state runs. The mangers operate using the technical mindset. I often see people describe managerialism as “communist” or “socialist” but neither of them capture what is happening in the technical society. Technique has become the dominant ideology, dare we say, the dominant political ideology of our day. If you wish to battle the evils of managerialism, you will be unable to do so without coming to grips with the power of technique. The power of the mangers, the Professional Managerial Class, is built on the power of technique. Their power comes from the power of the technical. Countering the managers means countering the power of technique, the machine and the machine mindset. The ring of power must be cast into Mount Doom.

So what are the characteristics of “the machine” and machine thinking, of technique? Ellul outlines seven characteristics of the technological:

Rationality: technique is always the application of rationality. It is never organic. Any rationally conceived plan, solution, method, approach, system and so forth is technical in nature. Whether that is applied to building rockets, running the government or growing churches, these rational approaches are technical in nature.

Artificiality: technique is opposed to nature. At its heart it is ideological. Technique never emerges naturally or organically, it is always developed and imposed. It is the creation of an artificial system. Technique destroys, eliminates and subordinates the natural world and makes it impossible to enter into a truly symbiotic relationship with the created world.

Automatism: technique is always pursuing the “one best way” to do anything. Whether that is a political system, or running a fortune 500 company, or testing intelligence, or teaching students. There is always a “best way” or a “best practice” for everything. Technique is always trying to achieve the most efficient way of doing anything.

Self-Augmentation: technique now proliferates now almost without human intervention. One technique suggests the next. Modern man is so absorbed in technique, so convinced of its superiority that without exception he is oriented towards technical progress, which is social progress.

Technical progress is non-reversible.

Technical progress is always geometric in nature.

Monism: the technical phenomenon embraces all the separate techniques in order to form a single seamless technical whole. This is a process of self-augmentation, where techniques now depend upon and reinforce other techniques.

People often wonder why big business has gone woke. It is because both business and government, specifically the administrative state, run on the same operating system, that of technique. Peter Laslett’s “The World We Have Lost” which examines pre-industrial England in order to document what life was like prior to the Industrial Revolution, makes the observation that it was during the transition to and growth of factories that there was also a corresponding growth in government at the same time. Prior to this, most of life and work was done within the family structure which would broadly include husband, wife and children, but often apprentices, farm hands, maids and so forth for a stable family business. As the production of goods moved out of the family structure and into the factory, a combination of state and factory replaced the family.

Both the state and the industrial factory come to be dominated over time by the technical mindset, dominated by machine thinking. Standardization, rational processes, automatism, process thinking begins to take over and permeate both the factory and the government. This is why the political dichotomy between those parties that focus on the interests of business and those parties that focus on improving the social conditions of society are in many ways two manifestations of the same phenomenon. Both business and government run on technique. In many ways, business is more managerial than the government, more imbibed in the technical mindset than is the managerial state. This is why professionals can move seamlessly between government and business and why the two are increasingly similar in outlook. They are in fact not two phenomenon, but one. If anyone who is desirous of smaller government and clipping the wings of the administrative state and is yet pro-business: this is not a serious political stance. The desire to shrink the size and influence of government should be accompanied by a desire to shrink the size, scope and influence of business as well. You cannot oppose the administrative state without wanting or needing to resist its operating system as well. If you are set against technique as a political and social ideology, you should be more opposed to its presence in business than in government, as it has far more influence in that sphere than it does in government because of the power of technique to make money.

Seeing the Inflection Points

Having thought about this a long while, short of some kind of global cataclysm, technology and technical thinking are here to stay. I am convinced that Ellul is correct when he argues that it is impossible to solve the problems of technology with more technology. Because of the a-moral ambivalence of technique and technical thinking, it falls upon us to make moral decisions about our use of technology. We need to be able to say, “Thus far and no farther.” We need to be able to say, “Stop.”

These judgements require wisdom. Wisdom is often squishy and difficult to pin down. It often means making different decisions in different situations. I have written on this elsewhere:

Making a wise decision often means being able to see into a situation clearly and determine the essence of it. What are we looking at in the moment? A situation completely ruled by the technical; or one in which technique and machine are in service to the human? Is man the master or is the machine mastering the man? What I want to do next is present a number of continuums and contrasts in which, I suspect, somewhere there is a place in which human beings can work with tools and maintain their humanity.

Embedded Knowledge vs. Managerial Science

One of the things which the technical impulse desires to do is to break down every task into its component parts and rationalize the process. The goal is to create efficiencies, to standardize the work and make the outcomes more predictable and repeatable. Every effort in project management and quality control is driven by managerial science. Technique rules. The goal is to remove human variance from the processes and outcomes. The goal is to remove the need for any sort of intelligent interaction with the work. All work becomes like the assembly line.

Lest you think this is just for occupations like manufacturing, you can also find technique applied to such diverse areas as accounting, customer service, even teaching. Use the right methods, the right process, and you can guarantee consistent results.

You might be thinking, there was a lot of training involved in most skilled trades down through the ages, how is learning good teaching methods different from how someone learned to be a stone mason or a carpenter? The key question is this: to what degree are these skills embodied? There are always routines to doing certain things. There is always a right way and a wrong way to use a tool. What form does this knowledge take? Where is it located?

If the work in question is reliant upon policy and training manuals, extensive computer systems, if it is broken down and rationalized it is of the technical. The degree to which the knowledge lies outside the person, the more likely it is to be governed by the dictates of technique. The more that these disembodied processes are person invariant, the less dependent they are upon any one person, the more technical they are and the more dehumanizing they are.

It has been noted in various quarters that test scores are falling, that people don’t seem as intelligent as they once were. I would not be surprised if one of the factors contributing to this is the nature of work ruled by technique. Work that is not governed by rationalized processes, that is not ruled by strict routines remains rich and rewarding. Relying upon people solve problems on their own forces them to engage their own powers in a way that builds and enhances who they are as people.

When knowledge of a task is carried within a person and not in a manual or within computer coding, there is a greater risk of variance, less control and perhaps less efficiency. It also requires a more energy and effort to train someone one-on-one as an apprentice. I remind people regularly that some of the greatest buildings in western history, the gothic cathedrals, were built without engineering mathematics, without CAD programs and they did not use project management software. Everything about building a cathedral was largely intuitive and was organically embedded within the members of the mason’s guild. Years of training and practice, generations of trial and error, enabled them to reach to the heavens using stone as their medium.

The degree to which knowledge is organic and embedded with people is the degree to which it allows human mastery over technique. The degree to which work becomes rationalized, systematized and turned into processes that are person invariant, is the degree to which we are mastered and controlled by technique. If you want to begin the process of freeing your business from bondage to technique, take all the policy manuals and burn them. A few simple rules, broadly applied and easily remembered with a deep embodied tradition is the human way to go.

Creativity as Being Unleashed vs. Creativity as Mastery

In the world ruled by technique, do we have a proper understanding of creativity? In the world where humanity was not ruled by technology, creativity emerged as a byproduct of mastery. Every craft and discipline, from masonry, to furniture making, to painting, to playing the piano are learned through a submission to both reality and to the rules and constraints of the discipline. Take for example the playing of a musical instrument like a piano. One must submit oneself to the instrument, to the constraints of musicality and musical theory, as well as to the instruction of the master piano player. In some sense, to become a master piano player, one must be mastered by the instrument. Creativity emerges through this submission to the discipline, constraints and reality of the instrument. It is out of this submission that mastery emerges, and it is from mastery that creativity emerges. This is taking the idea of embodied knowledge we talked about above to the next level. To embody knowledge you have both master it and be mastered by it. It must live within you.

In contrast to this, there are two forces in today’s culture that undermine this mastery. One aspect of this flows out of the idea of personal genius as it grew up during the romantic period. The idea is that within each of us there is a well of creativity that is being held back by the constraints and restrictions of society. Creativity by this way of thinking means being unleashed from the constraints of rules and conventions so that we are free to do as we wish. The enemy of creativity is repression. We must be true to our inner selves. Creativity means breaking down the barriers to free personal expression. In this mode, the idea of mastering a discipline is a kind of offense against the expression of one’s true self, one’s true creativity. The rules must be challenged and broken down, they must be deconstructed, so that we can be freed for creative self-expression.

This would seem to run contrary to the impulse of the technical to rationalize every process, to create a set of repeatable rules and processes that can produce repeatable results. Technique would seem to be the enemy of this understanding of human creativity, and in some ways it is. But at the same time, because all of the routines and systems have been depersonalized, broken down and turned into repeatable processes that are as person invariant as possible, they require almost nothing from us. The technological world does not place any demands upon us. Choice becomes a substitute for mastery.

As Crawford notes, it is the difference between learning to play the piano and learning to use an iPod. With the latter, you simply select songs, make a playlist and hit play. The music will come for hours. Making music on a piano is hard, requiring years of instruction as well as hours upon hours of practice. Playing the piano, though, is grounded in physical realty and has a direct connection to the instrument, to the process, the discipline, the art of making music. The iPod is a mediated experience, disconnected, abstract and portable.

From an early age these real, visceral experiences are taken from us. We are robbed of the challenge of learning skills. We select and consume. We no longer make or craft. If you want to create a style for yourself, you look online, you go to the store, and you select and purchase from a plethora of options. You are not tasked with patterns or sewing or the rest of the tedium of actually making and creating an item of clothing. Instead of learning to sew and create a stuffed animal from scratch, you go down to Build-a-Bear and choose from their many pre-selected and curated options. Once all your selections are made, someone else finishes off the product while you wait. You have the simulacrum of being creative without actually having to create anything.

Crawford gives another example. These days when we want a customize a vehicle, we go the the dealer or a specialty shop, we look through the catalogues and select from a menu of bolt on performance parts that are then installed by the techs in the shop. No more learning how to do metal fabrication or use an English wheel. No need to learn the art of preparing a manifold so as to eek out an extra one or two horsepower.

We live in a remote control world. We live in a world of passive consumption. We live in a world where most of our choices are determined ahead of time for us by someone else. Freedom is characterized not as mastery, mastery of self, of the world; but rather as choice, that is consumer choice from a variety of pre-selected options.

If we were to set up another continuum, the degree to which an activity requires skill, mastery, and has a visceral connection with the world is the degree to which a person has mastery over the technical. The more that you as a human must apply your skill to overcome the limitations with your tools, the more that you are master of that tool. The more that you can use a small number of tools to accomplish a wide range of tasks by exercising your wit and ingenuity, the more you are a master of technology.

If you are encountering a technique or a technology where you are removed from actual physical processes, where all options and choices have been pre-determined for you, the technology or technique has become your master. If your interaction with the world is mediated through a series of interfaces, that technology is your master. If you are reduced to merely selecting choices in a menu, that process, technique or technology has mastery over you. In this sense, every time you go to the mall to shop you are demonstrating your slavery to the whole technical system which brought you those end user consumer choices. A seamless end-user experience is the mark of a successful enslavement.

Bodily, “Handed” Work vs. Abstract Work

We tend to bias work that deals in abstractions as the “smart set” jobs. Yet, Crawford notes that there is a lot of intelligence in our hands. He bring forward a quote from Anaxagoras:

“It is by having hands that man is the most intelligent of animals.”

There is a lot to this. Because of the abstract nature of so much work in the digital age, we have lost this idea of embodied intelligence. There is a sense that for a craftsman, an artist, someone like our aforementioned pianist, that much of their intelligence is in their hands. It resides in the subtle feel of the product, of knowing intuitively when something is right. Kneading dough is another example. We tend to discount making things with our hands vs. doing abstract work with words and numbers using computers. Again, we might ask: are we as a society less intelligent because we no longer work with our hands? Crawford quotes Heidegger:

“The nearest kind of association is not mere perceptual cognition, but rather handling, using and taking care of things which has its own kind of knowledge.”

Even in a society that is not ruled by technique, there is some need for abstract thinking; but it is fair to say that the more involved we are with our hands in our work, the greater likelihood that we will be masters of the technology we use. To know the world we must do things in the world, with our hands. This is why you will find a lot of wisdom among people who work with their hands and why it seems like smart academic types who deal in abstractions seem completely divorced from the real world. They are. To know the world, we must be in the world, meeting it with our hands.

Repairing and Conserving vs. Buying New

Our technical world, with its emphasis upon innovation, technical progress and this idea of always moving forward tends to be biased towards what is new and novel and against what is old. This creates a great disincentive to repair or restore what is old. Technique becomes another form of fashion. We develop new ways of doing things simply to say we are doing something new. Stasis is bad. The saying goes, '“If you are not moving forwards, you are going backwards.”

We tend to replace things rather than fix them. We are sold new things as better, largely because they are new. There is a strong incentive to emphasize things that are secondary to function, such as aesthetics or features. Our machines must be laden down with ever more frippery that are incidental or unnecessary to the core functions of the product. In addition, products are increasingly less fixable. Fixing something is often similar in cost to buying a replacement product.

What we lose in this is an attachment to a product, a machine, a device. When it can be repaired or tinkered with, we develop a bond with the machine. We learn its ways, its peculiarities. As we maintain it, we develop a mastery over the machine. We invest ourselves in it. It gains life, being.

When we dispose of things, they pass through our lives. There is no incentive to exercise our will over the device or the machine. There is no need for us to fine tune a technique. Next week, next month, next year there will be a new technique that promises better results and we will grab hold of and implement the new, rather than perfect the old. We will retire the old devices and replace them with newer.

Because this bias towards the new, novel and innovative is integral to technique itself, the degree to which we are willing to embrace machines that can be repaired, are comfortable with old, proven ways of doing things, will allow us, I believe, a better chance to become masters of our machines, masters of our techniques. It also allows us time to evaluate the effects of new technology. If we understand that its harms outweigh its benefits, a bias against novelty will help us make the moral choice to stop using it. To always be on the quest for the new and the novel is a sign that we have been taken captive by the technical mindset.

The Problem of Scale

This piece has grown long already and much more could be said, but one more point should be made in terms of being able to “see” the inflection point. As we noted earlier, Laslett made the observation that the growth of the administrative state occurred at the same time as the growth of the factory. Throughout the book there is an emphasis upon the understanding that society was, for the most part, organized around the family, the cottage, the farmstead, the manor house and the church. Even though the old nobility and the gentry were at the top of the social and political life in 1600-1700’s England, about 20% of the villages were, for all intents and purposes, largely gentry free. Much of the organization of society was around the household, large or small. It could be a small nuclear family. But often there were farm hands, serving girls, apprentices and journeymen attached to the household. If you were taken into the household of another, the head of that household could decide if you were ready for marriage or not. If there was not a stable match or he did not think you would be able to support yourselves as a couple, you would not be allowed to wed. This idea that people were marrying in their teens in those days was just false. The average age of marriage was 23-24 for girls and 24-26 for young men. The higher up the social ladder you were, the more likely you were to marry young. Remember, also, most girls and boys did not go through puberty until their late teens because of nutrition and overall health. Romeo and Juliet was just what it seems: fiction.

Laslett also notices that in the colonization of America, those below the line of the gentry were much more common than they were in England. Even though the gentry gets all the credit, he notes, America was built by commoners organized into tight family units, much like they were back in England.

It was industrialization that swept aside this family structure.

Ellul notes, as we saw above, that it is one of the drives of technique to universalize everything, to standardize everything and to come up with the one best way of doing something. Because of technique’s power to make money, there is immense pressure to scale up, to reach the point where you are operating on economies of scale. There is a constant push to be more efficient and more productive, driving most every concern to expand and grow.

Crawford notes, though, that there is a social quality to meaningful work. The technical does not just alienate us from the real world, it also alienates us from each other. There are some things that just cannot be scaled. The imbedded wisdom in a community that sees each others work, the products of hand and mind and is able to connect the results of that work to specific people and a specific place cannot be replaced by an algorithm. And once this value is removed from a community, it is very difficult to replace it or renew it. This is the difference between the corner store or the national chain, the local bank verses the banking conglomerate. All of this embedded work cannot be replaced by technology.

The degree to which almost every function of society is rooted in the local, in the family and the community, whether those are businesses, government, schooling, whatever, is the degree to which they will be able to master technique. Once you expand beyond the borders of these structures, once you scale up in size, you can only do this through ever greater degrees of technical control and sophistication. Becoming masters of technique means intentionally shrinking the size of our world down to the size of family and village. The closer we are to that scale, the better chance we have to be able to master technique and root it organically within the value structure of that community.

Once you take a bite of the apple of technology and technical thinking, once you allow it to grow in scale and scope, once it begins to metastasize, there are no easy solutions in mastering technique. It means a wholesale change in our lives. Lives that will be more work, more physically demanding, less financially prosperous. But they will also be lives in which human values are able to flourish. Do I think this likely? Not without some shock that forces real soul searching. Presently, we are too enamored with our toys. But make no bones about it, we are slaves to the technical world. We are slaves to its patterns of thinking and the machines it produces. Technique crouches at the door, its desire is for you, but you must master it.

It would be nice to give an explanation of that point since I'm not sure what this actually mean: "Technical progress is always geometric in nature."

Hey, Kruptos, as a subscriber, I would like the option to let Substack read your posts to me. My two cents. :-)