Why The Meritocracy Isn't Coming Back to Save America

It's true. The Meritocracy isn't coming back, but not for the reasons you think. It has nothing to do DEI, but rather with scale and complexity and the necessary transformations to make both happen.

My intellectual journey has brought me down a number of different paths, leading to places and vistas that certainly seem odd today. I was educated in the late 1980’s and a good part of the 1990’s. There were certain movements afoot at the time. This really was the peak period for “the consultant” and the “management guru.” It was a time when absorbing the works of management gurus was de rigueur, even for someone who ended up studying for the ministry. It was a time when “church growth” was on the ascendency. I got introduced to the whole field of “management consulting” through a book on managing the process church renewal, specifically to Tom Peters, who, even to this day, remains something of a patron saint for the whole field.

If you are going to read management books, the early Tom Peters material from the late 80’s and 90’s is better than his later works in the 2000’s forward, mostly because he buys into diversity hiring as a path for excellence. In other words, politics began to undermine his core themes revolving around “excellence.” At the time, I didn’t have the grounding in political theory that I do now, and so I really wasn’t able to see the deeper philosophical implications in what Peters was encountering in the business world of the day. From the perspective of managerial science and technique, it is top notch stuff. Peters really was at the height of the game in this regard. If this piece tempts you to read any of his works, go for the older books like: In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best-Run Companies (1982, with Robert Waterman); A Passion for Excellence: The Leadership Difference (1985, with Nancy Austin); Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution (1987); and Liberation Management: Necessary Disorganization for the Nanosecond Nineties (1992).

Peters is good for insights like the “Management Paradox” which can also apply to societies as well. In order to succeed, you have to do something well and understand the core of your identity. You need to plow a deep furrow. If you are always trying to change and adapt, you never get good at doing any one thing well. At the same time, every organization has to be able to adapt constantly to changing situations and times, otherwise they will get run over by changing technology, markets and social situations and they will get out competed by their rivals. His main concerns developed out of his work as a consultant. He was brought in to help large moribund corporations become more competitive in the marketplace. Basically, companies called Peters in to help them deal with the downside effects of managerialism. Basically, his response to managerialism was to develop mechanisms that would encourage “excellence.”

Before we dive into some of the relevant ideas from Peters that can help inform us today politically, we need to quickly understand how is it is that corporations and governments came to embrace managerialism and all its subsequent downside effects. The important point for us to understand is that managerialism and the administrative state are a necessary feature of scale. No one sets out to become a moribund corporation. And it’s also true that when people began to implement the professional bureaucracy, applying the tools of “scientific management” to government, they were looking more at the outcomes they were hoping to achieve than the administrative monster they would create.

Joseph Tainter argued in The Collapse of Complex Societies that one of the leading functions of a society is that it is a problem solving mechanism. At some point, as a society grows, it embraces greater complexity in order to solve certain problems which it is facing. It makes the necessary adaptations, introduces new ways of doing things and increases the level of societal complexity in the process. Tainter argues that initially, these increases in social complexity bring about huge gains. The outputs far exceed the inputs. But, as the society moves through its life cycle, every new problem adds new layers of complexity, usually accompanied by the growth of society, and, over time, these social systems begin to eat up ever greater amounts of the society’s resources. Eventually, a tipping point is reached where the inputs outstrip the outputs and this is when bad things happen for civilizations. Tainter outlines three basic paths for the civilization at this point: either a slow gradual decline, or a break up into smaller more more manageable pieces, or total collapse. For interest, he argues that America passed this tipping point somewhere in the 1970’s.

The key point to take away from Tainter for this piece is that introducing managerialism when the society is ascending is both beneficial and necessary for the society to properly scale up and realize itself as a society. But all the benefits of managerialism are accrued during the growth phase as society scales in complexity. This is similar for corporations, but on a smaller scale. For a business to grow from a “mom and pop” family business or some some “start up” to become a Fortune 500 behemoth requires that you make certain changes in management style, type and structure. You have to embrace the necessary changes that enable you to grow in scale.

At a certain point you have to become “managerial.” You have to find a way to abstract and rationalize the culture you have built as “command and control” owner, instantiating this in policy and “corporate culture” such that the combination of culture and policy will allow management decisions to be effectively carried out at scale across the whole company. In a sense, what is though of as “corporate culture” has the same function that “ideology” has in government organizations. Once you get to a certain level of scale, it is necessary to transition to this style of management. I suppose in theory it is possible that there is another way to do it, but the ubiquitous nature of “scientific management” globally is a good argument that this might be the only way to do it. There is a certain “necessity” to it demanded by scale. In other words, once your country or your company reaches a certain level of scale, it has no choice but to embrace some form of managerialism. While there is a certain necessity to this transformation, and there are huge benefits which come from their initial implementation through the growth phase, eventually you reach a point where the nature of administrative systems begin to become an anchor on the company or the nation.

There are two main reasons for this. The first, and more universal across time and different civilizations — that is, it includes those that never used “scientific” management techniques — is that once you implement certain social mechanisms of problem solving, these mechanisms themselves require maintenance. Inevitably, every solution will itself come with certain trade offs or reveal certain new problems that then now have to be managed with new solutions that add yet more complexity to the society’s social systems. And this complexity itself now also has to be managed. What begins to happen is that more and more of society’s energy, its people, its resources, goes towards maintaining the system itself. At a certain point, the very complexity of the civilization will begin to overwhelm the civilization, such that the burden of maintaining the civilization becomes too great for the civilization to bear. For example, it is generally assumed that we should be maintaining a growth rate of 2%. But Tainter argues that to sustain a long term growth rate of 2%, you need grow research and development expenditures at a rate of 4-5% every year. Either growth will at some point cease, or R&D expenditures will make up the whole of the economy. This is what is happening across the civilization. When you reach this point things begin to decline, the civilization breaks up and becomes less complex, or a rapid collapse happens.

The secondary reason comes from the nature of scientific management techniques themselves. The management techniques that are the cornerstone of almost every institution from business to government to non-profits is the way that they allow organizations to run effectively at scale and over time with consistent outcomes which are relatively person invariant. As we noted above, the policies regimes and the organizational culture and/or ideology allow organizations to reach a size and scale inconceivable by previous historical standards. Good policy. A good training regimen. Consistent quality protocols. The proper incentives. The right technological tools. All of these combine to create an environment that runs effectively and efficiently, producing consistent outcomes over time. Additionally, these systems elevate the floor in terms of reducing the low end variance of workers with less ability. You can expand the size of your workforce and increase its overall level of quality by using a combination of policy enforcement and training to offset deficiencies in intelligence, ability or personal judgement. Also from a personnel perspective, the structures allow smoother transitions from one manager to another manager over time, again ensuring consistent outcomes.

The downside cost of both the elevated floor of your personnel outcomes and consistent quality outcomes over time is that you give up your high end variances as well. By elevating those at the bottom above where they would have been otherwise, the price you pay for this is that you stifle your very best and brightest. The system actively resists their emergence. When a society, a business or even a non-profit is on the rise and begins to initiate and implement these systems, because of the returns gained from the added scale, the losses coming because of gradually reduced high end excellence are not nearly as apparent as when the organizational system is mature and you are both expending energy maintaining the system and are operating within a narrow band of consistent outcomes. Once the organization matures and the initial gains have been accrued, decline begins to set in naturally as the negative byproduct of past successes.

This is where a management guru like Tom Peters gets invited in to help. His role is to help revitalize the now moribund organization. A lot of what he did was look at the ways in which various organizations managed to overcome, sidestep, or do what needed to be done in order to spark excellence in an organization. I began thinking again about Tom Peters’ writings because it wasn’t until recently that I had read the necessary political philosophy to understand what he was trying to do, that is, the political implications of his managerial writing. Much of it is simple stuff. Doing things that get you outside of the organization’s policy framework to understand your people. Management By Walking Around, MBWA. Hiring good people. Protecting them from human resources and higher ups who would stifle them. You job as “the boss” is to get your people the resources they need and to protect them from the company’s bureaucratic system that would stifle their excellence.

Peters would highlight a “protected” operation within a larger company, such as Lockheed Martin’s “Skunk Works” that produced the SR-71 spy plane. As a concept, the idea is that you take the company’s best and brightest, put them in a special division that is not subject to the usual corporate rules and controls and you just let them loose to cook, create and otherwise be excellent. He highlighted various examples of companies that fostered pockets of creativity, outside of the ordinary rules, that could then feed the normal moribund system new products and methods. Give people time and resources to work on private projects. This is how Post-it Notes were invented. Get rid of committees and put people in charge of things and let them run them they way want. Treat your department like your own fief, ignore corporate and just pursue greatness as a unit. The other thing he often talked about was scale. If your company is big and cumbersome, break it up into units no bigger than 250 people. Spin the business units off and make them responsible for their own profit and loss statement.

Another example he highlights is businesses that run almost without organization. Where the organization is built around the project or event and then ceases to exist after the need for the event is over. You bring together people with key competencies around a specific task, all of whom know their job, know how to work with others, whose value is based entirely on reputation, and they come together, get what needs doing done at a high level, and then they go home when the project is complete or the event is over. There are many businesses that run like this, from event planning to construction, where they keep only a skeleton crew of full time staff. The rest are all hired on contract.

The interesting thing is, once you start looking at political theory, there are some interesting parallels. As an old time lord, you could maintain your own army or you could hire mercenaries when needed. A department head that protects his people from human resources and upper management and ensures that his staff have the resources they need is taking on aspects of the role of the “lesser magistrate.” When you spin off a bunch of independent business units to increase their effectiveness, merely expecting them to return a profit every year for head office, which is now little more than a holding company, the resemblances to feudalism start to jump out at you. The minor lord is given his fief, and as long as he pays the tithe to his lord, all is good.

But there are limits. Certain heavy industries only make sense when they are done at scale. A steel mill. An automotive assembly plant. An oil refinery. A chemical processing plant. This is especially true in the realm of the political. While it is possible to run a major corporation as a holding company that is a majority owner of 100 small independent business units raging in size from 50-250 employees, governments don’t really work this way. While is possible to run a major construction company with a minimum of capital investment and without a lot of full time staff, there are limits to how much you can do this in government. In many ways, businesses attain a lot more flexibility because they can pass off many necessary functions to the government, for example, they don’t have to build their own roads and utilities — this is true even when governments contract that work out — and they don’t have to work out with each participant anew the rules framework and enforcement mechanisms that make a modern business environment possible. Much of modern society and the modern economy which makes it happen, is build around standardization across the system and the centralization of power. “Just-in-time” global supply chains are possible because American carrier groups keep shipping lanes free from piracy. American carrier groups are possible because the American government runs a centralized administration that harnesses and organizes the resources of a whole continent, and the 350,000,000 people who live there. These people need to have a standardized culture that is maintained by propaganda across the system. A system of this scale requires scientific management techniques. Because of the nature of a highly integrated global business and governmental apparatus is it always working towards standardization across the system, of working towards the one best way of doing things.

The necessity of this system for the American global economic empire is that increasingly more of the system’s energy will be directed towards the maintenance of the system itself, away from other activities, like generating wealth for the imperial centre or the ability to project military strength globally.

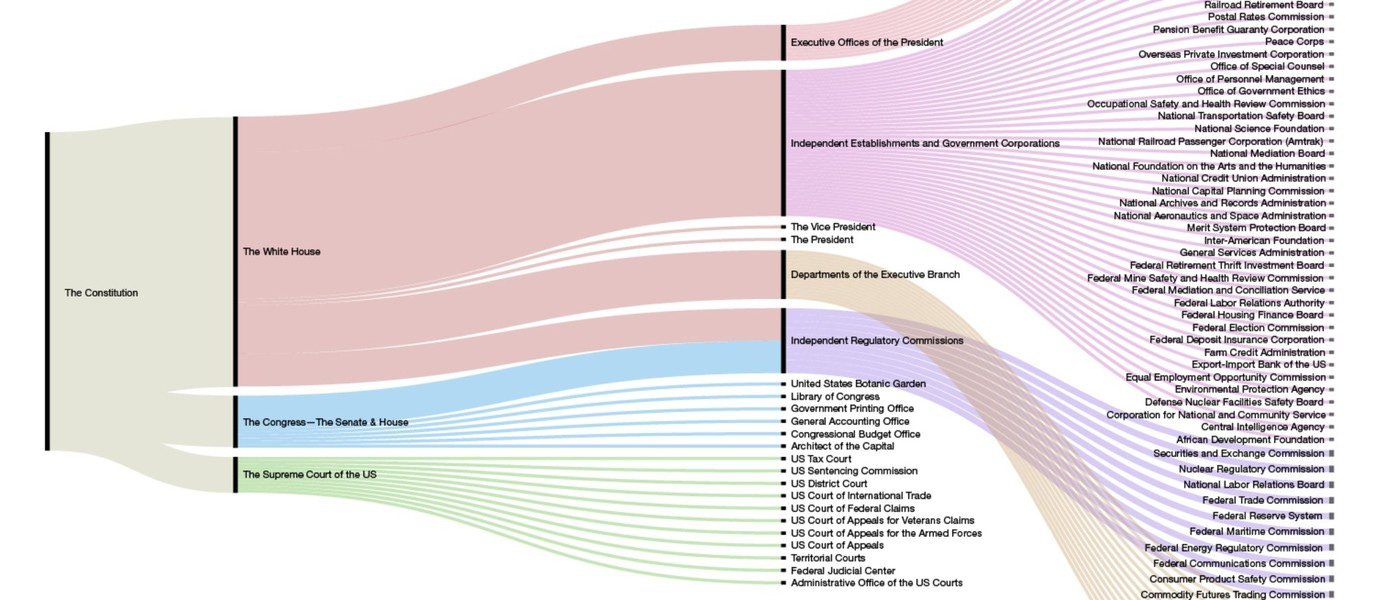

But why can’t the system be reformed? Why can’t we use the insights of a Tom Peters to spark excellence in the system? Why can’t we bring back the meritocracy? Lets says that you put together a group, a new independent agency. Let’s call it, for simplicity sake, the Department of Government Efficiency. It’s too big a job for one man of course. Just looking at the scale of the American government will tell you this.

So, you bring on board a top notch staff of efficiency experts whose sole task will be to monitor the efficiency of other government agencies. What have you just done? Well, you have added a new layer of complexity to the system. This layer of complexity will itself have to be managed. And, what you have done, in working to make the government leaner and more efficient, is actually grow the governmental system. And while there might be initial gains to be made from implementing the DOGE, it will not be long before the DOGE itself becomes an institutionalized locus of power and patronage and mediocrity.

You might be thinking, why can’t we just do like what Elon Musk did at Twitter? Fire 80% of the people? Get rid of departments wholesale. Devolve power back to the states, that sort of thing? Why can’t we do like the corporations, and make government like a kind of holding company and just run things like a bunch of 250 person IBUs? They did a version of this in the Middle Ages and it was called Feudalism. Remember, what makes the modern world what it is, what gives us the prosperity we enjoy, is the economic benefits that come from operating things at scale. Economies of scale are a thing. There is a reason why economic activity, and with it political power, wants to expand the scale at which it operates. It allows you to gain efficiencies which can only be unlocked by means of economies of scale. But the cost of operating at scale is that scale must be managed, and this management consumes societal resources, and the consistency necessary to operate at scale means mandating a uniform mediocrity across the system.

But this hasn’t answered the question of why you can’t do like Musk did, fire a bunch of people or just get rid of a department? You can. And this gets into the whole arena of risk management, the “Too Big to Fail” scenario. You have this complex system, a very complex system of government and business partnerships. In theory it is a good thing to allow a certain number of businesses fail during an economic downturn. It takes excess capital out of the system. It removes inefficient and underperforming players. You cut away the dead wood. Its painful, but you emerge on the other side a little battered, but ready now for new challenges. The business world likes consistency. A burdensome regulatory environment is, in some ways, almost preferable to removing all the rules and governing agencies and creating a wild west situation. You can fire 80% of the employees at Twitter. When you do this, you take a tremendous risk. You are gambling that you can keep everything running well, or even improve things doing so. But there are no hard guarantees that this will be the outcome. Maybe Elon Musk can make it happen. But how many others can make it happen successfully? Federal, state and local governments in the US employ about 22 million people. What happens when you put 17.5 million people out of work? What happens when you mostly get rid of the federal government and put everything back into the hands of the states? Now you have, in effect, created a continent with 50 independent countries. How do you manage trade and the economy between all these state entities? How do you manage the global shipping lanes? How is the continent defended? Do you end up doing something like the European Union? Oh. Wait. That’s the current federal government.

This does not get into the problem of the fragility of the system. What happens when you start messing with things. Closing down agencies, this sort of thing. Do you inadvertently initiate cascading instabilities across the system? Do you bail the banks out and make a few very rich people even richer, or do you let their banks fail, and then watch as a cascading series of bank and business failures happens across the system because of a lack of liquidity, sending the global economy into a deep recession? It might not happen. Maybe, like the employees of Twitter, people find new jobs, pick up the pieces and after some initial pain, everything bounces back. That is kind of the theory, right? When the Home State Savings Bank of Cincinnati, Ohio fails, how bad can get? And what if its ends up being more than 10% of a nation’s banks failing? This is what you run up against.

As you begin to think about the work of someone like a Tom Peters and his efforts to inspire companies to pursue excellence, you begin to realize that the kinds of things he is suggesting largely involve implementing techniques or creating situations which allow people to ignore or operate outside of the requirements of the system of scientific administration at scale. You can create administration-less organizations in certain industries or in specific situations, but you cannot run an entire economy at scale this way. You can break companies up and the turn head office into a holding company, but in governance you can’t really do that and run a global economic empire. A military where everyone goes home after the battle is done and are called up again the next time they are needed and all the soldiers maintain their own weapons, well, that’s more or less how feudalism worked and it was superseded first by centralizing monarchies and then the modern state because these were a more efficient and effect means of harnessing military and economic power at scale. Over time, the most proven means of doing this is scientific management techniques. These systems provide enormous ability to harness resources and people at scale, they are effective and increase the overall efficiency of the system — people always knock on these bureaucracies for being inefficient, and they can seem that way, but when compared to any alternatives, they are remarkably efficient and effective — and they create consistent, predictable outcomes, while creating a reasonably high performance floor. The downside cost of these systems is that they institutionalize mediocrity, irrespective of any policies of diversity, equity and inclusion. Eliminating DEI might raise the overall performance of the system, but it is not thereby going to make it all about achieving excellence again. You will still have mediocrity, just a mediocrity that is marginally better than the old mediocrity.

You will always be able to created targeted pockets of excellence where real meritocracy is allowed to blossom. And doing so is a good thing. But excellence doesn’t scale. There are only so many truly exceptional people. You can gather them all into a governing oligarchy, but this too can only be scaled up so far before you run out of excellent people. You can work to raise the overall excellence of your people through education and the inculcation of virtue. But again, there are limits. The only way to make something like excellence scale is through the use of administrative technique. And the cost of this is to institutionalize mediocrity across the system. You can break the system up. But now you lose all the benefits of managing things at scale. And there are certain activities that can only be done at scale, like being a global sea power. The other potential risk of breaking things up is that you create cascading failures in the current system.

And so we end up back again grappling with Tainter’s conclusions, that once a society introduces complexity into its social systems to solve problems, you put that same society on the road to its eventual downfall. It may have a good, long run of success before that happens. This thing that we romanticize as “the meritocracy” was really the product of a unique period in the life cycle of our current civilization on its ascent where men of excellence were able to take advantage of the power of administrative systems at scale, reaping those benefits before the downside costs of those same systems began to manifest themselves. But you can’t go back. You might be able to prolong things by creating targeted pockets of excellence here or there, but to do so across the system would largely mean blowing the whole system up. There are three options for the end of a civilization. One option is a slow steady decline where the civilization retreats back to a more manageable scale. The British Empire might be a good example of this. But it also benefited by the rise of America. The second option is a total collapse, where, within a matter of decades, the civilization is more or less just gone. The third is that the empire breaks up into its various constituent parts. Things are worse, but they allow the parts to regroup and perhaps some of the parts can begin their own societal rise again. This third option, is, in many ways what a Tom Peters “A Passion for Excellence,” “Thriving on Chaos,” or “Liberation Management” type process would entail if you were to pursue it civilization wide. You can’t both keep your moribund late stage civilization and make it great again at the same time. The meritocracy isn’t coming back. It simply can’t do this while keeping America more or less what it is today. Its a political illusion.

I find that you raise valid risk assessment concerns in regard to the mission of DOGE.

Vivek Ramaswamy appears enthusiastic when I've heard him talk about scaling down the bureaucracy. He puts me in mind of the Javier Milei video where he says "Afuera! Afuera! Afuera!"

As for Elon Musk, you had only to draw our attention to the 80% job terminations at Twitter to ask what of the knock-on effects if this same measure is applied at scale.

There are preparations in the works for a sweetheart deal for many in the administrative state. I heard about it last night while watching America This Week.

At one point Matt Taibbi and Walter Kirn talked about plans in the works to concoct a new kind of legal category - a sort of pre-immunity but sheltered under the name "pardon". There are generous offers from unnamed patrons for high paying positions after leaving the public sector (the high pay is all Trump's fault because these workers have to anticipate the need for funding large legal expenses). Walter Kirn suggested that they were essentially being paid off by people on the side of l'acien regime in whose interest it is that these bureaucrats go away quietly.

While this doesn't address your larger concern of cascade effects, I thought you would be interested to know that DOGE will face no resistance in some corners.

I wonder if retreat from empire, the third option, is what is on offer in the incoming Trump administration. It goes along with "America First" and with President Trump's basic rejection of supranational organizations.

It would have been a bit of a hard sell, I suppose, to have campaigned on end of empire explicitly. Alhough, I do believe many, if not most Americans, would be happy to see exactly that. There is a strong appetite for laying aside the role of policing the world and healing our own country. Personally, I'd be thrilled with walking away from NATO completely as a start.

Granted, this would introduce an element of instability globally, as various nations jockyed for regional position. However, it is clearly American empire itself that is currently the source of great dangers to peace and stability in the world.

Obviously, a strong national defense would be necessary as a deterrent against opportunism at a time of perceived weakness. Also, there are very powerful vested interests who will push back hard.

There is so much to consider in the dilemmas you present here. As a high level starting point, though, do you think a retreat from empire is soon in the offing?