Why the Administrative State Renders the Idea of Elite Replacement Theory a Non-Starter

One popular idea in dissident right circles is that what is needed is to oust the existing elites and replace them with new set of elites. I wish it could work, but unfortunately, it won't.

“What radicalized you?” This is one of the questions that gets asked fairly regularly in dissident right circles. Everyone here has an “origin story.” One day you are card carrying Republican who reads National Review and talks a lot about “the free market” and warns people about the dangers of “socialism;” next thing you know, you have a anonymous Twitter account, the pictures on your phone are filled with frog memes and you are a regular listener of Auron MacIntyre’s YouTube channel. You have jested in contrast to the leftist refrain that “real Marxism has never been tried” that “real Fascism has also never been tried.” You are firmly a member of the “dissident right,” whatever that means at this particular moment.

You have been helped along on this journey by ingesting various books like James Burnham’s “The Suicide of the West,” “The Managerial Revolution,” and “The Machiavellians.” You found your way to Mencius Moldbug’s “Unqualified Reservations.” You might even try your hand at reading the works of Carl Schmitt. You dig into the past to read older authors like Georges Sorel. Sam Francis’ “Leviathan and Its Enemies” finds its way into your hands. You probably spent some time dabbling with the “Intellectual Dark Web” before moving on to real dissident thinkers. You know what NrX is and @0x49fa98 means something to you. You dig into the various theories of what is wrong and what can be done. “The Cathedral” is part of your regular vocabulary. You talk about “the exception” as meaningful term. Doomerism is a serious philosophy. You have read the Foundationalist Manifesto. In amongst all this dissident right discussion, one idea regularly bandied about is that of “Elite Replacement Theory.”

It is a simple idea, really. As James Burnham pointed out in The Machiavellians,

“…no societies are governed by the people, by a majority; all societies, including societies called democratic, are ruled by a minority”

Burnham here is picking up the idea of the “Iron Law of Oligarchy” which argues that all sociological groups, from the small community or organization, up to the scale of the nation state, are always, regardless of the stated means of legitimizing power, including democracy, run by a small group of elites. Elite replacement theory argues that rather than focusing on winning elections, that what is needed is to replace these oligarchic elites with your own elites. They must be developed and cultivated and made ready for the task. Some argue that replacement happens in regular cycles.

One of the corollaries to this is the effort to identify who these elites are and the means by which they network and build the bonds necessary to nurture and sustain their power. Family networks. Schooling like the Ivy League universities: Harvard, Yale, Princeton and others. Organizations like The World Economic Forum come under scrutiny. You follow the money. In Canada they even have a name: The Laurentian Elite. The argument is that we need to identify these people, their networks and the places where they hold power and pull the strings behind the scenes, and we need to oust them and replace them with our own leadership elite.

I will not argue that these people and their networks are without power. That would be foolish. They wield tremendous wealth and influence. While this oligarchy is real, they are not the decisive reality. There is no cabal of “Illuminati” behind the scenes pulling the strings. That said, this group has situated itself within the decisive reality and are adept at navigating and using it to maintain their position and accumulate the wealth which comes from being the key managers of the decisive power reality. These elites are the technicians who navigate and manipulate the vast network that we call the “managerial state.”

It would seem natural to think that our problem is that these elite technicians of the current system have bad ideas and are wielding this system towards ends which are terrible and undermine the ability of our society to flourish. The thought goes that if we can replace them with our people who have good ideas and thus put the system towards good ends that this will allow society to once again flourish. Others would argue that if we take away their toys, that is shut down, or vastly scale back, or break up the managerial state, that this will reduce their power and allow the people to flourish on their own once the state is off their backs. Or better, we do both at the same time. Unfortunately, both plans are misguided because they fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the managerial state and how its technicians operate within it. It also fails to recognize that the managerial state in its many forms cannot be reformed or controlled. It is fundamentally a creation of liberalism for liberalism.

The first mistake is to think of administrative state like an empty vessel, a neutral entity, empty of content, merely waiting to be filled with the substance of policies by whomever is in control of the vessel. This understanding stems from the general view of technology which thinks of it as “neutral.” Technology is inert, just waiting for you to use it. What matters is the uses towards which you put it. You can do good things with technology or bad things with technology. It is up to us to choose how to use the tools we have at our disposal. Technology itself is an inert thing, merely waiting to be wielded by people towards ends chosen by its operators. This, argues a thinker like Jacques Ellul, or a Marshall McLuhan, is a fundamentally mistaken view of technology.

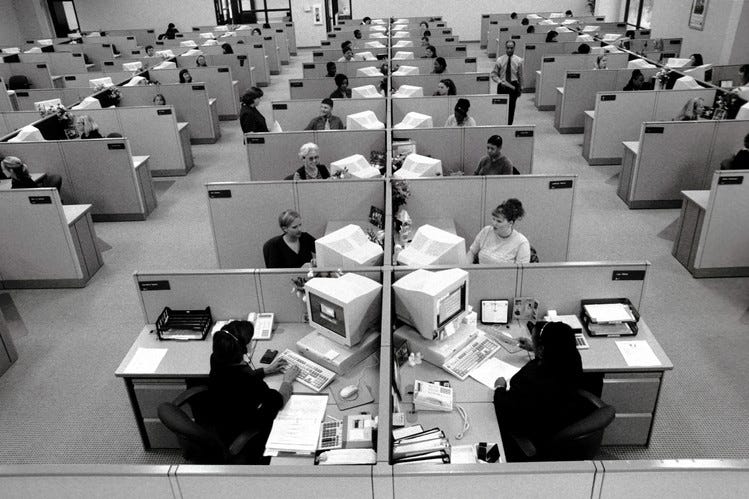

Before we look at the nature of technology and how this affects our understanding of the administrative state, we first need to grasp that technology is more than merely the machines, tools and devices that we use. Technology is fundamentally a way of thinking about the world. Ellul calls this “technique.” Technique, the technical way of thinking, he argues, looks to take human activities, break them down, abstract them, rationalize them and then systematize them. The goal is to improve consistency and efficiency, thereby producing repeatable results. The idea is to separate any and every human task or organization from its fallible, variable, organically embedded context in persons, memory or community, abstracting it out of its particular human context to rationalize it, universalize it, thus making it portable and reproducible. Then, once the system has been developed, people are then trained and inserted back into the system.

Technique has been immensely powerful and is responsible for much of the prosperity and success of the modern world. It is everywhere. We see it in the assembly line, in quality control processes, accounting standards, teaching methods, customer service methods, administrative systems and more. It is used everywhere. It is the idea that drives the policy manual. You can figure out every potential situation and can develop a plan or procedure to account for it. You can take human variance out of the equation. You don’t have to worry about people’s intelligence or capabilities, as long as you have the right systems and processes in place. Additionally, you can use technology to augment or replace people. The machines often exceed human capacity. Primarily, though, at its heart, technique is a way of thinking, a way to approach problems.

This way of thinking, argues Ellul, has a number of identifiable characteristics:

Rationality. Technique is always the application of rationality. It is never organic. Any rationally conceived plan, solution, method, approach, system and so forth is thus technical in nature, regardless of its outward form or its place in the historical progression of technical development. Thus, something like the American constitutional plan, because of its inherent rationality (i.e. It did not emerge organically. A group of men met together and developed the system. A planning committee.) is essentially a technique based solution. Whether this rationality is applied to building rockets, running the government or growing churches, these approaches are technical in nature.

Artificiality. At its heart, technique is opposed to nature. It is ideological. Technique never emerges naturally or organically. It is always developed and imposed. It is the creation of an artificial system. Technique destroys, eliminates and subordinates the natural world and makes it impossible to enter into a truly symbiotic relationship with it.

Automatism. Technique is always pursuing the “one best way” to do anything. Whether that is a political system, or running a fortune 500 company, or testing intelligence, or teaching students, there is always a single “best way” or a “best practice” for everything. If this single best way has not been yet found, the quest is to continually refine existing techniques until it is. The goal of technique is always working to achieve the most efficient way of doing anything.

Self-Augmentation. Once it reaches a tipping point, which we passed long ago, technique will proliferate almost without human intervention. One technique suggests the next. It become the default way to approach every problem, every new situation. Modern man is so absorbed in technique, so convinced of its superiority, that without exception he is oriented towards technical progress. Technical progress is equated with human progress.

Technical progress is non-reversible. What this means is that there is an axiomatic nature to technique. Technique and the technical are seen as a sign of progress. Non-technical means are seen at best seen as quaint, but generally as backwards or retrograde. To reject technique is to reject the very idea of human progress. All flaws in technique thus must be fixed by new and supposedly better techniques.

Technical progress is always geometric in nature. As the technical system proliferates, its complexity and sophistication grows exponentially. Thus the problems which accompanies it will also grow exponentially. But because of the abstract, rationalized nature of technique, the whole system becomes increasingly abstract in nature.

Monism. The technical phenomenon embraces all the separate techniques in order to form a single seamless technical whole. This is a process of self-augmentation, where techniques now depend upon and reinforce other techniques. It is a single grand entity which encompasses much of life and strives to include all things within its purview. Everything must be subjected to technical rationalization and control. In this sense, technique, as an ideology is inherently totalitarian in nature. It desires to subordinate all things to its exigencies. More than this, it insists that all thinking be in accord with the demands of technique.

Why is this important for understanding the nature of the administrative state? Just as Carl Schmitt made the argument in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy that the parliamentary system of governance based on such ideas as “the marketplace of ideas” are not content neutral but are, in reality, built for, and sustained by, liberalism, so too, and perhaps more so, the administrative state is built for, and sustained by, technique. The structures, tools, systems and policies of the administrative state are artifacts of technique. Almost the entirety of modern administration is technique based. An argument could be made that technique is akin to “unification theory” in physics. Technique is the ideological operating system upon which, not just the west runs, but all technological societies. It is the way in which almost every situation and problem is approached. Anywhere where you find an org chart, quality control, a policy manual or you do things like a SWOT analysis, you are dealing with technique. Whether it is in business, education, non-profits, churches and para-church organizations, and, yes, government bureaucracy, they all run using technique in various forms and levels of sophistication. Technique is fundamentally about control, efficiency and consistent results. It is a society wide approach to almost every situation and every problem. The administrative regime is everywhere. Once the system has produced a “best practice,” such as “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion,” it quickly becomes ubiquitous.

N.S. Lyons, in his recent piece, The China Convergence,

also makes the argument that managerialism is fundamentally an ideology with definite characteristics:

Technocratic Scientism. This is the belief that everything including society can be fully understood and controlled and managed by technical means. They look at the world as a grand machine that can be understood by human reason, abstracted, rationalized and then engineered to be continually improved.

Utopianism. The belief that through the application of reason and technique that we can perfect society. This is the idea of “progress,” that we as a society are moving “forward” towards a better future. Thus history itself takes on a moral character. The embrace of the traditional takes on a character of immorality, in that it desires what is “backwards,” thus holding back the better future ahead.

Meliorism. This is the belief that all human problems can be solved through the application of technique. Every problem has a technical solution that can be instantiated through management, policy and systems.

Liberationism. The axiomatic understanding of history, with its directionality towards utopia through the means of technique, biases thinking towards one of liberating people from past practices, ways of organizing society, customs, habits, and morality. The past must be dispensed with so as to make ready for the better future technological systems will bring us. We must constantly break down the barriers which restrain us from moving forward.

Hedonistic Materialism. The idea that we can achieve happiness through the fulfilment of material needs and psychological desires. If we have a desire, there should be some “solution” that can satisfy this desire. Consumption is a moral good. The restraint or repression of desire is a bad thing from which you need liberation.

Homogenizing Cosmopolitan Universalism. This is the “monad” applied writ large. All cultural uniqueness and particularity is erased or ignored. Human beings are fungible cogs who can be trained to fit into, operate and manage “the system” anywhere equally in any place. Move people around where they are needed as needed. Any forms of localism, particularism or federalism is inefficient and backwards, an obstacle to progress and thus immoral. The quest is always for the single universal system. Globalism, world government, the multinational corporation are all good things. Economies of scale are desirable in every situation. Every system that is good must be scalable and therefore must be scaled up to include all things.

Abstraction and Dematerialization. The belief that what is abstract and virtual is more real and better than actual physical reality. Physical reality is messy. Once we are liberated from the demands of the physical, we can remake the world. The world must conform to the system, to the plan, to progress.

What we must see when looking at technology in the forms of devices and machines as well as in the nature of management systems is that none of them merely inert artifacts. They do not gain their moral intent from how they are used. Managerial techniques and institutions are the products, the artifacts of an ideological framework, a way of thinking about the world that is itself not neutral. The administrative state must be seen as an artifact of the ideological system which produced it. Laying beneath political doctrines like “progressive liberalism” and “free market conservatism” or even doctrines like “constitutionalism” is that all of them run on the same root operating system: that of technique.

Let’s say that you are willing to accept this reality, that the world runs on technique. Can’t we develop better techniques than the current ones? Isn’t part of the problem that the systems are being designed and managed towards terrible ends? There is truth in this. But unfortunately, given the nature of technique, the solution cannot be to replace bad techniques with good techniques. Ellul examines this question in his book The Technological Bluff, making the case that technology is not neutral. Nor can techniques be classified as “good” or “bad.” The idea that we can replace bad technical systems designed towards bad ends, like the current regime of “diversity, equity and inclusion,” with good systems designed towards ends which will help society flourish, is fundamentally misguided and misunderstands the nature of technique.

Technique is neither, neutral, good, nor bad, says Ellul. Rather, technique is ambivalent. It does not care. With this, he is able to acknowledge that many techniques, technical systems, processes, policies, machines, oversight regimes, organizational structures, all of it in any of its forms are often introduced with good intentions. People introduce techniques and technologies because they think that by doing so they are making the world better. But, says Ellul, by understanding technique as ambivalent, we are better able to grasp its effects over time.

He argues that this ambivalence has four distinct characteristics:

First, all technical progress has its price.

In other words, there is a cost to using technique and technology. You cannot opt out from paying the price when you use a technology. Every technique—plan method, system—every technology—machine, device, tool—will have positives, that is, good things that come from its implementation; and it will also have negatives, that is, bad or evil things that come as a result of its use. There is no escaping this two fold nature of technique. All technology has its positives and its negatives, its good and its bad. The technology does not care. When you use it, you will get both.

Second, at each stage it raises more and greater problems than it solves.

Every time you use technology and technique to solve a problem—usually one generated in the first place by technique—there will be positives for sure, but you will generate more problems than you solved. Those problems will grow with each new layer of technology. They will grow in number, complexity and abstraction along a curve that is exponential. As society becomes more technically sophisticated, so too will its problems grow in direct relationship to the level of complexity.

Third, its harmful effects are inseparable from its beneficial effects.

This states more boldly and expands upon the first point. Bad effects will come from the use of every technology. There is nothing you can do in terms of design or planning to prevent the negative effects from coming because they are directly tied to the benefits you receive from its implementation.

Fourth, it has a great number of unforeseen effects.

Not only can you not gain benefits from technology without the accompanying harms, there are a whole lot of both good and bad effects that you cannot account for in advance. There is no amount of planning or testing that will reveal all of the effects of a technique, both good and bad.

What this means in practice is that replacing, say, a DEI policy regimen, with a conservative policy plan will do good (just as the DEI policy regimen does do some good) but with it will also come certain costs, certain negative effects (just as the DEI regime comes with certain costs, certain ills). These cannot be avoided, and many of them cannot be predicted. This is the nature of technical solutions. You might make things better in one way, but those benefits will always come with a price, a set of unavoidable negatives or evils that accompany the goods they generate.

Marshall McLuhan observed something similar with his dictum, “The medium is the message.” He argued that the fact of the use of a technology was more important than the content. For example, a significant impact of the automobile is how it changes the nature of mobility rather the content of any one trip you might make. The real significance of the lightbulb is the fact of the lightbulb and not any one particular room you might light up. The real significance of the television is the effect of watching it and its place and role in our lives rather than any one show you might watch. It is obviously better to watch wholesome programming as opposed to porn, but in either case you are being shaped by the “fact” of the television. So too, the real significance of the administrative state is the “fact” of the administrative state, not any one set of policies. So while you may prefer the wholesome policy recommendations of a Chris Rufo to the hardcore pornography of woke DEI policies, both are not the real “message.” The true message is the “fact” of the administrative state through which both policy programs are implemented. The fact of the administrative state, as a technical system, is subject to Ellul’s four rules of technical ambivalence we discussed above. Getting your people in to control the programing does not change the fact that you are using the same system. This system is more decisive than any one policy. The technical system, including the administrative state in all its forms, for the reasons we discussed above, is inherently liberal in orientation.

At a deeper level, there really is no such thing as a “conservative” policy regime when discussing the administrative state. All policy regimes use the same basic operating system, that of technique. Thus they conform to the seven characteristics of technique talked about above. Because this technical orientation is, as McLuhan says, the true “content,” the policies and the management systems take on technical characteristics, that is, they are defined by the medium of technique. This is why all bureaucracies whether small or large, public or private, end up looking and functioning much the same. The system as a whole is driven by an ideological bent: that of technique which is fundamentally in harmony with liberalism as the two share most of the same characteristics. The system of the technical administrative state was built by liberals for liberalism. If you ever wondered why Conquest’s second law — “Any organization not explicitly and constitutionally right-wing will sooner or later become left-wing” — is true, this is why. Once you embrace technical and administrative systems, once you embrace technique, you begin a battle against the natural ideological inclinations of technical thinking. This is true for government, business and non-profits, even seemingly tradition bound organizations like churches.

But what if you are willing to accept the system as is? Maybe you look at the cost of bringing down the whole system and think to yourself that the ends do not justify the means. Can’t we try to reform the system and control it the best we can? Maybe the best we can do is the governmental equivalent of couch potatoes watching wholesome TV? The challenge is that once you go down the road of using technique in governance, the end outcome is that you effectively lose control of the government. The bureaucracy becomes the ruling sovereign.

“The idea that the citizen should control the state rests on the assumption that, within the state, parliament effectively directs the administrative organs, and the technicians. But this is just a political illusion.”

In truth, argues Ellul, the politicians whose stated role is to exercise oversight over the government become the vehicle through which the plans of the experts who staff the bureaucracy acquire legitimacy.

“The organs of representative democracy no longer have any other purpose than to endorse decisions prepared by experts and pressure groups.”

Every cabinet member and all of his key political appointees are nothing without the bureaucratic infrastructure. They need it more than the infrastructure needs the cabinet members. We must understand that the modern state is not a centralized command and control hierarchy. Rather, it is an extensive decentralized network of political organs. Part of the problem is the sheer scale of the bureaucracy.

The idea that a cabinet member can issue an order, make a decision, and this will be able to fundamentally change the nature of the bureaucracy is pure fantasy. Once an order is issued by a minister, it escapes his control. The matter takes on an independent life. It will circulate within the various branches of the ministry and eventually the bureau will decide what it wants to do with the directive. It is entirely possible that orders will emerge in line with the initial decision, but more frequently nothing will emerge. The decision will simply evaporate in numerous administrative channels and never see the light of day. Often this is done on purpose when the politicians and the bureaus are not ideologically aligned.

It has gotten to the point that the bureaus can effect actions independently, in their own interests, and are able to curtail and sanction the activity of the politicians. We have come to call this activity the work of the “deep state.” But it is merely the action of the administrative state demonstrating its power in such a way as to curb the influence of the elected officials.

We must understand that the complexity of the bureaucracy precludes any single decision being able to affect the whole of the administration. There is no single center. It is impossible to get the whole government onto a single page. The diversified inter-related network of decision making nodes are not responsible to anyone, not the politicians and certainly not the citizenry. No one person, or even a small handful of persons, are in charge. This is the state. This is the power that runs the modern nation state. This is the power that runs the increasingly globalized administration. This administrative network is not limited and confined to government, but extends across the entire administrative system in business and non-profits. This is more true the larger and more bureaucratic an organization becomes.

We should not talk about the administrative state as an organism, as it does not obey organic rules. An administration is a technical abstraction. While there are people that staff the bureaucracy and they have personal strengths, motivations, flaws and their own agendas; while there are identifiable channels of communication, both formal and informal; while there can be a culture to an organization with its own habits and peculiarities; while there are power struggles within an organization with status issues and rivalries and class divisions, all of this is secondary. To focus on the people and personalities who staff the bureaucracies, however high up on the org chart they might be is to be looking at the trees and so miss seeing the forest. We must remember that whatever “human” elements there are to an administrative state, these happen within the confines and limitation of a techno-rational system.

Within this system, no one person is ever able to influence the whole of the bureaucracy. Ellul notes that there is no differences in bureaucratic administrations. There is no difference between a “democratic” administrative state or the communist administrative state. Nor is there a difference between public administrations and private corporate administrations. They are all techno-rational systems. This is why corporate entities seem to be mimicking public sector entities. This is why American technocrats look favorably upon the work of Chinese technocrats and their administrative state —and why N.S. Lyons noted in his excellent piece that they are becoming increasingly more alike. An administrative state is an administrative entity no matter what context it finds itself in. It obeys its own rules. The technical imperative of techno-rational administrative entities is always expanding and reinforcing its unity so as to create a singular technical system running all things. All bureaucracy is bureaucracy.

The politician, on the other hand, is divided. He must gain and keep power. He cannot give his full attention to enacting administrative reforms unless he first gains and keeps power. In addition, the skillset necessary for the gaining and keeping of political office are quite different from those that make one an effective administrator. Because of the politician’s need to gain and keep power—even the dictator, the Caesar, must attend himself to gaining and keeping power—he will never be an expert administrator. He will never have the expert’s grasp of the administration. He will always be an amateur with an amateur’s grasp of the bureaus. Thus, the politician’s power over the bureaucracy is always theoretical because he is not first of all an expert administrator and the bureaucrats know this.

Yet, the politician must put his faith in the bureaucracy. The truth of the matter is that the vast majority of legislation originates in and among the experts that staff the administrative state. He will often sign into law legislation that he has never read, does not know and cannot know.

The larger the bureaucracy the more impossible it is for the politician to even have effective knowledge of the state, much less have power over it, to direct its course. Scale is a significant part of the problem. The administrative state makes large scale government control possible. Even if a politician can assert control over the administrative state, this will be a temporary situation. The experts will return soon enough and balance will be restored. It is true that the dedicated politician can effect the system. He can improve methods, controls, chains of command, internal coordination and efficiency. But these reforms do not make the administrative state more accountable. The better it runs, the more autonomous it becomes. The more that the administrative state is reformed, the more powerful and independent it will be. And the more independent the bureaus become, the harder they will be to reform in the future. A bureaucracy is always moving in the direction of greater size, scope and independence. As the administrative state penetrates the political machine and starts to affect and direct the decision making process of politicians, is the degree to which the bureaucracy becomes the state.

If you want to challenge the bureaus that make up the administrative state, you need a staff of policy experts and management specialists. You need your own elite mangers. This idea is all the rage now on the right. We need to foster our own expert class to counter the expert class of the left. This is an illusory effort doomed to failure from the start. It does not matter and will do little or nothing. By developing its own cadre of experts, the party is in effect developing its own bureaucracy to challenge the bureaucracy of the state. At best you will end up with two battling bureaucracies. But because all bureaucracies are dictated by the techno-rational imperative, the two battling bureaucracies will in the end more resemble each other than they will represent two meaningful alternatives. They do not result in less bureaucracy or better bureaucracy. It always leads to more bureaucracy. More rule by experts. This is the inevitable result of any efforts to develop policy centers or think tanks or one’s own reformist set of experts. They all in the end add to the total web of bureaucratic expertise. The whole system become Kafkaesque.

No longer do people interact with government through their elected officials, through the voting box. The citizen’s relationship with government is through the bureaucracy. And because the idea that the individual person can in any meaningful way influence the administrative state diminishes as the bureaucracy grows, the impotence of the citizen grows as the administrative state grows. The bureaucracy slowly becomes an omnipotent force in society.

Our bureaucratic state is authoritarian not because of any one political decision or any political ideology. Rather, it becomes so because every day thousands of decisions are made over which no one has any oversight nor any recourse against. Most of these decisions are routine and mundane.

Stakeholder groups are no better than the parties. The moment a group starts organizing in order to influence the state it will begin to take on and form its own bureaucracy of experts. Eventually this group will be asked to “advise” the government, at which point it simply becomes and extension of the administrative state itself. This goes for all unions and NGOs as well as think tanks. They all eventually become extensions of the bureaucracy. Once their interests become bureaucratic, these so-called activist groups will then start to resist input from the masses. The more influential a group becomes the more their function is not to bring the input of the citizen to government, but to keep the people in line.

Eventually the state will get the better of all groups organized to reform or counter the state. Once these local and intermediary powers are co-opted or eliminated, the field is open for increased administrative state authoritarianism. The more you organize to oppose or reform the state, the larger and more influential the state becomes.

This is why Ellul argues in Autopsy of Revolution that “the state,” that is the totality of administrative systems in the public, private and non-profit sectors, is the enemy. He also makes the argument that what made revolutions what they are, different from a mere revolt, is that the revolutionaries had a plan. Revolutions require managers to take the ideas of the revolt, and turn them into a concrete plan that can then be institutionalized. In this sense, your response to current system cannot be to have a “plan,” because this plan, conceived of rationally in advance, will be a thing of technique. It cannot be otherwise. Any revolution against the system that proposes a new system, for this is what a revolution is, will simply replace the current technical system with a new technical system. I talk more about this in my recent series on Autopsy of Revolution:

Ellul makes the case that what is needed is a revolution against revolutions. That is a polite way of saying, “burn it all down.” He recognizes that this is a utopian position that will basically result in the destruction of modern life as we know it. In a sense, the only way out is that billions must die. I go into his argument in more detail in part six of the above series. In the end, I cannot make the calculation that the ends justify the means. This means finding another path: building a parallel polity founded on a different set of values other than that of technique. So what are these values?

I have argued it must be rooted in strong, spiritually vibrant traditional Christianity. Beyond that, it must value the person, their abilities and their flourishing over technique. It means giving up consistency and efficiency and the power of technique. It means a smaller world organized organically around communities. It likely means an economy organized around household enterprises and a relationship with machines and technology that fosters and encourages this smaller scale. Knowledge will be embedded in the people and not in abstract systems, techniques and machines. They will not need policies because their way of life is taught person to person culturally. These communities also have to be prepared to provide a reward system that is fundamentally different than the wealth generating machine that is the modern capitalist administrative state. Yes, you have to be able to feed, clothe, house and likely arm the people. But they will have to endure some level of hardship. The leaders of these communities will have to be able to inspire people such that they are able to reject the rewards and comforts of the regime for the hardships of being a community of resistance.

We began by talking about elite competition and replacement theory. The argument I have been making is that the idea that we can raise up a counter-elite who can seize control of the current mechanisms of governance, the administrative state, is a futile endeavor. This system was built by the bourgeoisie managers for the bourgeoisie mangers. It runs on the ideology of technique, the root ideology of the modern era. You cannot step in and make it anything other than what it is. There was a time when leadership what rooted in persons and the person was decisive in regards to governance and the wielding of power. A theory of elite replacement made sense within those older, pre-revolutionary, pre-industrial, pre-technical, pre-administrative state realities. But in today’s techno-rational administrative system, it really is the system that is now in control. The people and persons that fill the system are on one level necessary. You need warm bodies of a certain level of competency to operate the machine. But by and large our leaders are not really leaders. They may be better described as machine operators. We do not need a replacement set of machine operators to man the machine, even if they are of a better quality than the old. But we could use leaders who are capable of calling out of this vast globe spanning technical system a new people, a people that can live in the world, but not be of the world, so to speak.

So who are these men? And they will be men. First of all they are men deeply immersed in the presence of God: a new Abraham, Moses, David, Josiah, Ezra, Nehemiah, or Paul, Peter or John. Beyond this, I found Carl Schmitt’s characteristics of a dedicated ruling elite to be a compelling starting point, in part because his list focused on the quality of the persons rather than their technical skills or other abilities. Here are his characteristics of a dedicated administrative and leadership class from Legality and Legitimacy:

They are incorruptible.

They are separated from the pursuit of money and profit.

They have a superior education.

They feel a strong sense of duty and loyalty towards the state and its effective operation.

They cannot be co-opted by interest groups.

They are a stable class of people. Entry to this class is not open to the whole of society.

They have a high personal and moral quality.

The elite self-recruits and decides for itself who will and will not be a member.

What it seems that Schmitt is grasping at is the hope for a new nobility capable of providing a distinct contrast to the current administrative class. This is essentially it, I think, even if one would argue with the characteristics he lists. We need men who can help form and shape a community of contrast to the regime that runs on its own exigencies, its own motivating and organizing principles separate from the regime.

Eventually a point of confrontation will come and if we are victorious it will mean an end to modernity with all its ills and benefits together.

I suppose one could argue that this is elite replacement theory let in through the back door. Perhaps, if you squint hard enough, that is what is happening. But it cannot be another long march through the current institutions or some grand coup or another revolution, all of which will, in the end, strengthen the system. It is time to begin thinking outside of the box that is the modern western world, to embrace the idea of post-modernity. Who are the men who can lead us out of our captivity to the techno-rationalist system of managerialism?

While these fine men lead an alternative system, I'd like to see us women organize to thoroughly ridicule the current matriarchal system. Women are best equipped to take down these devouring mothers. It's amazing how sensitive bureaucrats are to mockery. Most of them reached their positions without merit, and deep inside they know it.

Your piece is not actually arguing against replacing the new elite with better elites. It demonstrates instead that whatever elite replaces the current one must be be a qualitatively different elite. We don't need new *managers,* as the two arms of Capital (the market and the bio-political state) are the problem. But we do need better leaders, and we should cultivate the new elite.