What is America?

This question, and its corollary, "Who is an American?" seems like a minefield. Any answer you produce feels like it will blow up in your face. But answering it is vital to the moment.

“What is America?” Now, who am I, a Canadian of Dutch descent who merely spent a good chuck of his 20’s in the US for grad school doing opining on the nature of America? I am not a native. I am not an expert. But that aside, this seems to me to be a pressing question for the moment. I am not sure the answers are as easy or as obvious as they might seem. They are complex, and this is part of the problem. There is no easy answer. And in some ways, Americans themselves are too close to their own situation to get enough detachment to really answer this question properly. I am of the mind that the contradictions and conflicts in the possible answers hinder the nation’s leaders in their decision making. It also holds back the dissident right in its response to the regime. I am also of the opinion that this question lies in the background to the rise of Christian Nationalism. There seems to be a hunger to know the answer, and Christian Nationalism is one such attempt to plant a flag and say, “This is who we are.” So, we wade in to see if we can make a contribution.

The recent Hamas attacks in Israel got me thinking about this question again, in large part because of the intensity of the discourse. Politicians and political hopefuls are running to get in front of cameras and onto social media to make histrionic assertions like “Israel’s interests are American interests.” I was like, “What? Why?” I suppose that could be the case. But the least you could do is make the argument as to why this is so. A couple of examples, should suffice. A Lindsay Graham tweet:

This gem from Nikki Haley:

But, it seems that the opinions of Graham and Haley are not shared by everyone. Recent immigration over the past few decades has brought a sizable population of Arabs and Palestinians to American soil as landed immigrants and citizens. Their sentiments are quite different. They support the Palestinians and Hamas. And strangely enough, these differing groups both typically vote for the same party, the Democrats. This led to demonstrations and counter-demonstrations in New York City’s Times Square.

That got me thinking about the commitment in American foreign policy to support Israel. I put my thoughts together in a thread, making the argument that it is an odd combination of coming to grips with the Holocaust combined with the Dispensational Premillennialism common to many American Christians. With ethnic Jews voting Democrat and Christians voting Republican, this ensured a relatively strong bi-partisan support for the nation of Israel. You can read the whole argument here:

Is America an Ethnicity or a Land of Immigrants?

Looking at the table below from Wikipedia, it affirms what everyone pretty much knows: other than a notable number of ethnic Germans and Dutch, the population was predominantly made up of peoples from the British Isles. English, Scotch, Irish, Welsh. The other significant group was African slaves, about 20% of the population as a whole at the time of Independence.

The percentage of Blacks in the population fell from that point until the 1920’s when the numbers bottomed out around 9%. The percentage of European whites rose to about about 90% of the population, depending on how you counted Spanish speakers. Things have changed rapidly since then with the largest growth coming in the category of “Latino,” who now make up just under 20% of the population.

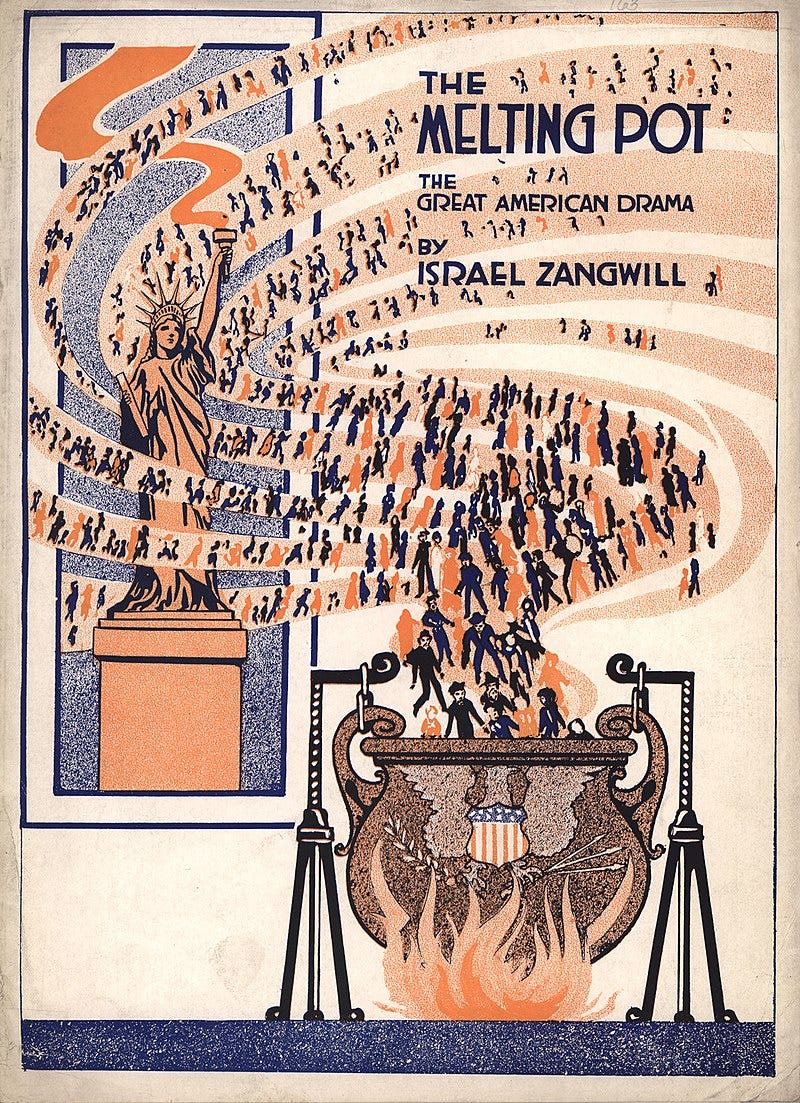

This predominantly British culture began to change in the early years of the 1900’s. Although, a term in use since the 1700’s, the idea of America as an ethnic “melting pot” took off in the early 20th century after a play of the same name.

America would be formed out the crucible of all these peoples coming and intermarrying. To some extent this did happen. But many ethnic and racial groups remain distinct, including the black population. Many rural areas still have stable populations of Swedish, German, and Dutch ethnic communities, for example.

But this idea, and another going back to the same period, when the poem “The New Colossus” was written, helped shape this idea of “America as a land of immigrants.”

"Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

This idea came to dominate so much that it even shifted the meaning of the Statue of Liberty, it becoming a symbol of the hopes of the immigrant coming to America.William M Briggs recently wrote that one of the reasons America gets itself entangled in so many conflicts is because of immigration. The drumbeat, constantly, is that America is a nation of immigrants.

This mantra, alongside “diversity is our strength,” is used beat down any objections anyone might have to immigrants, legal or illegal. We are all “hyphenated.” In the 20th century, there is some truth to this claim. But people don’t easily give up their ethnic ties and attachments to the “homeland.” Interests from “back home” do end up shifting and shaping American foreign policy.

Yet, at the same time, there are those with deep ties to the early settlers, a chain of lineage. There is such a thing as an ethnic American. When your family has been in a place continuously for 400 years (I mean, think about it: the end of the Roman era was in the 400’s for Gaul. By the 800’s it was firmly a Frankish kingdom), at what point do you become ethnically “American.” It is an interesting question and many Americans feel this sense of attachment to their family heritage. But at the same time, many blacks have family histories almost as long. Are they also ethnic Americans? Why or why not?

While this does hint at part of an answer, one that runs very deep for some, it is also a point of conflict and tension with those who claim America to be a nation of hyphenated people, an immigrant nation. How many generations does it take to become an American? The Founders seem to indicate a mere two generations is what it takes. If you come, your children born on American soil are as much American as someone whose family has been here since the colonies, or so we are told. They can run for the office of President. So what is the cut off? Two generations? Three? Five? Ten? I have argued elsewhere that people bond at a level that is “spiritual” in nature. How long does it take for a community to become bonded? How long does it take for you to become an integral part of an established community. It is quite possible to be the “new people” in a community 20 or 30 or more years after moving to a new place.

Once the process of intensive immigration began in the 20th century, though, this question, in some ways, for better or for worse, over the objections of the “old stock” families, became largely moot. The “nation of immigrants” was the ascendant idea. But that said, because of the divisions over this issue, we cannot make it the core part of the answer to the question: “What is America?”

Is America a Place?

As with the previous question, it might be tempting to give a resounding “yes” to this answer. America is the “New World.” There was a time when Americans thought of themselves not first of all as belonging to These United States of America, but rather to a loose federation of individual states. The common example given is that of the Virginians whose self-image was very much that of a “Virginian” and not that of an “American.” This type of understanding recognizes that it is hard to be shaped by the geography of the whole of the New World, when this place is a continent wide zone with multiple geographies, having an obviously different cultural effect on peoples of different places. The land of California helps shape its people, as does the plains of Texas, Oklahoma and Wyoming. Florida is very different from New York. New England again has its own geographic influences. The Bayou is quite a bit different from Chicago or Detroit. Cities and suburbs are more cosmopolitan, less rooted and less attached to one particular place. Cities, while different from each other, are again more different from rural places. Suburbs seem the same almost everywhere, but differences do occur.

There is one complex of mythic stories that does seem to capture the imagination of all Americans, that of the establishment of the colonies, celebrated in the rituals of Thanksgiving. There are also the stories that surround the settlement of the west. The wagon trains. The cowboy towns. The Indian Wars. There is something very Faustian about the drive to conquer and settle the west. Pressing to the horizons. But these notions of colonization and settlement are very different from that of immigration. The former brave an untamed land and out of this wildness, they impose their will upon it, shaping it and making it their own. The immigrant, on the other hand, comes and reaps the benefits of the hard work done by others who came before him. For those who are from old colonial and settler stock, long attached to a place built by the generations who went before them, they can easily feel an understandable resentment towards newcomers who don’t appreciate the price paid for today’s life.

The other meaningful geographic division is between that of the North and the South. Loosely categorized, Northern industry dominated a largely Southern agrarian population. When the South wanted to go its own way, the North forbade them and went to war to prevent the succession of the South. Much of the dynamics and character of that geographic split, even with a century of intensive immigration, still shapes the character of the nation, but not in a way that creates unity.

Further, immigration brings a dynamic were people, even several generations later, retain a spiritual connection to their homeland, even when born in America. This is true for me. A second generation immigrant from the Netherlands who loves the geography of the north and the winter weather, still feels more at home in the Netherlands. Immigration, I would argue, creates a wound that, for many, does not heal even one or two generations later. These connections and attachments mess with foreign policy, as noted correctly in the piece above by William M Briggs. One of the dynamics that skews Canadian foreign relations with the Ukraine is the large Ukrainian immigrant population, leading to the awkward moment wherein a Ukrainian “patriot” was celebrated for his past resistance to the Russians in WW2. They neglected to mention that he expressed his love for his homeland and people by joining a Waffen SS unit.

We have seen this immigration dynamic play out this week in the bifurcated response to Palestinian aggression and atrocities in Israel. On the one hand, there are ethnic Jews who support Israel, many of whom are lobbying for an American military response. Others of Palestinian descent, many recent immigrants, are demonstrating and lobbying for the Americans to take the side of the Palestinians against the oppression of Israel. Does this confusion happen if America were a unified ethnic community? Would this even be an issue?

Is America an Idea?

Because of the uncertainty with the above characterizations, Americans in the 20th century have embraced this notion that America is a set of principles above all else. I have argued elsewhere that this is not really a new thing, but is foundational in the abstractions used to turn the revolutionary impulse into a concrete plan and a functioning set of institutions that would instantiate the revolutionary plan. It was very much rational, abstract plan, a set of ideas, cooked up in back rooms by members of the bourgeoisie managerial class.

"We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

America began as a rational plan, a more perfect plan, a kind of policy manual for the new nation. Ideas have been a part of America from the very beginning. They were the cutting edge ideas of the day. Democracy. The marketplace of ideas. Rights and freedoms. The rule of law. Equality before the law. The balance of powers as instantiated in the three branches of government: the executive, the judiciary and the legislative, each having their role and jealously guarding their powers.

There were other ideas as well. The manifest destiny. The land of the free. The land of opportunity. The beacon on a hill. Religious freedom was a core part of what America would be. Many came to America to establish a certain kind of Christian community.

But this idea has been carried so far that I have heard the argument made that anyone who embraces American principles of democracy, no matter where they live are in fact “Americans.” You merely have to embrace American ideas and you too will be an American. This ideological basis of America was contrasted with the Marxism and Communism of the Soviet Union in the middle part of the 20th century. We are for freedom, especially the freedom of the market. We oppose socialism and communism. This is who we are, this is what makes us American. The idea of small government and limited regulations were contrasted to the central planning of the Russians. American freedom against Russian state control. As much as people resist this idea, especially those with a deep ethnic heritage and attachment to the land, to the living traditions of America, there really is something to this notion of America as an idea.

There are two particular constellations of ideas that seem decisive to me.

Is America a Commercial Enterprise?

German writer Carl Schmitt made the argument in “The Concept of the Political” that America really isn’t a people at all. Walking through the arguments above, you can see that he has a point. Schmitt’s argument was that the state exists as an expression of a unified people, to guard, nurture and protect the interests of the people. In contrast to this, Schmitt argued that American individualism, the emphasis on the protection of private property, as well as one’s personal rights, was an effort by the bourgeoisie merchant class to guard their property and business interests from being encroached upon by the government.

“The bourgeois is an individual who does not want to leave the apolitical riskless private sphere. He rests in the possession of his private property, and under the justification of his possessive individualism he acts as an individual agent against the totality. He is a man who finds his compensation for his political nullity in the fruits of freedom and enrichment and above all in the total security of its use. Consequently, he wants to be spared bravery and exempted from the danger of a violent death.”

Schmitt argued that American individualism and rights made it a kind of anti-state. The idea of America was to protect your personal, individual interests, generally business interests, from society. He called America an economic co-operative masquerading as a state. This dovetails into the idea of America as the land of opportunity. The independent businessman is still seen in many ways as an American archetype.

When America was largely a nation of shopkeepers, tradesmen, small business owners and farmers, this idea made a lot of sense. But as industrialization took hold and the power of rational management grew, the power of the monied classes grew. The power of the corporation grew. Big business was a thing. But who was looking out for the people? Who was protecting the people from the power of business? The people came second, largely because the idea of “rights” was not so much designed to secure the welfare of the people as a whole, but to ensure the success of the commercial ventures of individuals. This commercial emphasis goes back to the very beginning, to the reasons for the American Revolution itself. The revolution was driven primarily by commercial interests, questions of taxes, trade and regulation. The colonies wanted to manage their own business relations.

As American influence expanded, naturally commercial and business interests expanded at the same time as America grew into a global power. But it has struck me for a long time that America has used soft and indirect power to expand an empire that is mostly commercial in nature. Why did it not capture resources and turn remote regions into provinces directly governed by the American state apparatus? America certainly had the military power to conquer and impose direct control over these lands as provinces. Why the use of soft power? This brings me to final piece of the puzzle.

America: “The Good Guys”

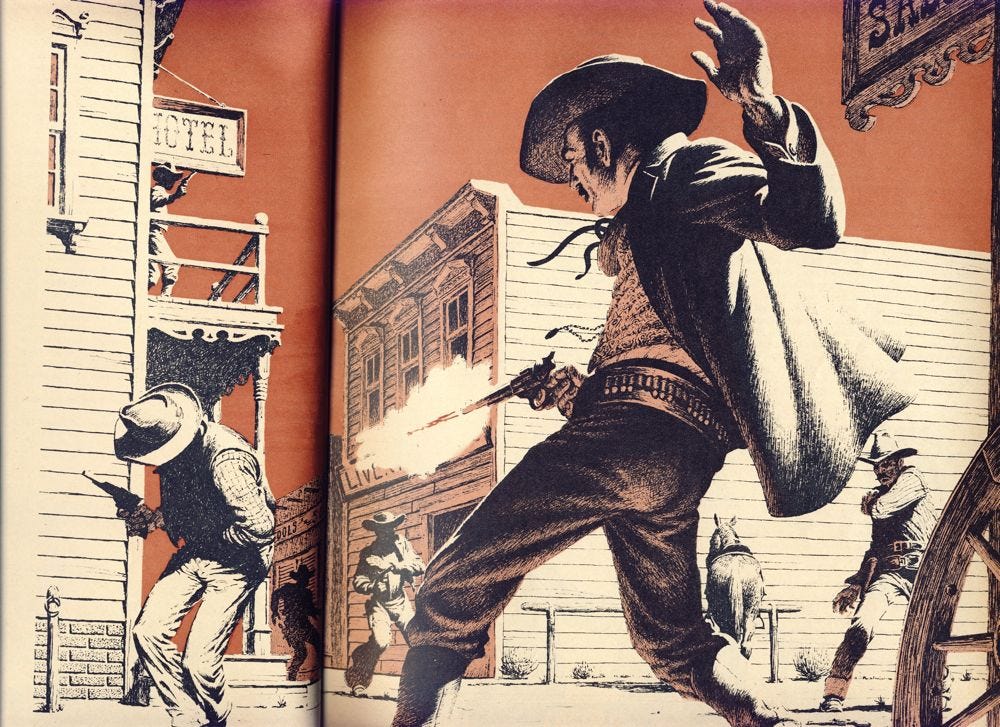

This to me is the decisive self image. Americans see themselves as the “good guys.” Look at the myth making of American movies. The gun slinging sheriff who rides into town, rounds up the bad guys and restores law and order to the frontier town.

We want superheroes. Captain America. We see things through the lens of good vs. evil. America must always be on the side of good. America can not simply have “interests.” The American state cannot simply act because it is good for the American people and will benefit them, regardless of how it is perceived by other nations. This does seem to be an affectation of all western states, but as the standard bearers of “The West,” it seems to be a particularly strong current in American identity and culture.

This does undermine the idea of America as a commercial empire. The good guys don’t simply seize the Middle East for its oil. No, the good guys respect the sovereignty of other nations. It can promote “democracy” and “rights” because these are good things. Being the “good guys” also aligns well with the idea that American society is a world leader in “human progress.” America must us its position as the global superpower to lead the way in stopping climate change, ending racism, and promoting transgender rights. The American state seems to operate indirectly, rather than directly. It facilitates trade deals for business interests that are only loosely connected to America as a nation, a people or a place. In some ways, this keeps the hands of the state clean and allows them to always be the “good guys.”

Only recently did the US Navy give up its tag line: “A Global Force for Good.” Its cringe. The tag line was cringe when it first came out, and its cringe today. But this kind of advertising campaign does not get generated in a vacuum. On a deep level people believe this about themselves. You are not really supposed to say such things out loud about yourself. It opens you up to charges of hypocrisy. But it exemplifies something deep in the American self-image.

We were the good guys when fighting the Germans and the Japanese, even when dropping nuclear weapons or carpet bombing cities. We were the good guys when battling the Russians during the Cold War. Ronald Reagan and his “Axis of Evil” brought the Soviet “bad guys” down. After 9/11 we were definitely the “good guys” in Afghanistan and Iraq. We are certainly the good guys in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, right?

This “good guy” image is reinforced even when movies present stories of disillusionment. The same with the real disillusionment and betrayal many felt over the Global War on Terror. Twenty plus years. So little to show for it. So many compromises made. How does one get disillusioned, anyways? You discover that the world is a lot murkier than you were told it was. You discover that perhaps, in spite of all the propaganda, you are not the good guys after all. But you wanted to be the good guy. You thought you were the good guys. You were told that you were one of the good guys. To discover that is not the case, changes how you feel about yourself and your country. Something was taken from you and you were used. It’s not a good feeling. Friends lost their lives. We were supposed to be fighting for something important, something good.

Yet, in spite of recent stresses to this self image, it persists. American progressives see themselves as carrying the mantle of the good guy image and would be even better if not held back by retrograde Christians and other traditionalists. There is an almost religious conviction surrounding this good guy image for progressives as they struggle to end racism, bigotry and inequality. Additionally, many Christian leaders struggle with the idea of a Christian “realpolitik” because, if the now secular leftist state styles itself as the “good guys,” Christians need to show Americans, and the world, that they are the “really good, super duper, extra good guys.” There can be no hint of the “bad guy” among Christian politicians. Christians always take the high road. Christians always condemn bad people. This leaves them vulnerable to manipulation and accusations of hypocrisy, weakening their public position.

Republicans and Democrats often channel the same impulse. Once a clear bad guy-good guy binary has been established, American foreign policy can be directed to aid the “good guys” and punish the “bad guys” often through economic sanctions. When there is military action, it often happens through proxies. Its much easier to remain the good guys when others are doing your dirty work for you. When Americans do get involved militarily, the rules of engagement are often such that they hinder the task of actually winning the conflict. You can only win decisively if it can be done without tarnishing the good guy image. Being the good guys means that you must build nations and promote democracy, freedom and the rule of law. Being the good guys means that we cannot dominate. We must apologize for our failings and own our mistakes. We are the good guys because we are enlightened and progressive and acknowledge our own failings, our racist past. We must open our borders. Only bad guys would refuse to share the prosperity we enjoy with others. We must make ourselves less so that others might be elevated and all people can be equal. We are so good that we would argue that there is nothing inherently good about America. After all, are the good guys.

So, what is America? America is the land of the good guys. This image will be harder to maintain as the empire recedes and as resource scarcity becomes more of a thing. America will have to exert more direct power to secure resources. It will be less and less able to act everywhere as the global sheriff, always riding into town to defeat the bad guy. Choices will have to be made. This means abandoning allies. It will mean the decisive use of direct power, no matter how harsh, how bad. Can Americans shed this desire, this need, to be seen as the good guy in order to maintain the commercial empire it has built? I am not convinced that it can, which will reinforce the general sense that America is weak, not up to doing what need to be done. Nor am I convinced that it can resolve the contradictions between being a commercial empire and being the “good guy.” Will hard power be asserted to secure commercial interests, or will they be slowly abandoned as America clings to its good guy image?

Thus far, the easy abundance which the dynamism of the the American managerial class has secured through technique and technology has reached its peak and is now starting to wane. That abundance made possible America’s role as the global policeman. It’s good guy image depended upon the material prosperity it could provide. What happens to that image when it can no longer provide global prosperity? Can prosperity for Americans as a people be maintained by shedding that image? But the problem there is that America, especially in the 20th century, has not really existed for its own people, but rather for its commercial interests and the maintenance of its good guy image. Of one thing we can certain, much uncertainty is ahead. America, and Americans with it, are facing an existential crisis. I am increasingly coming to the opinion that Americans must grapple with themselves and who they are, that coming through the current crisis will mean shedding the “good guy” image, finding something else around which build their identity as a people, as a nation and as an empire.

A commendable inquiry.

America did not succeed because of its diversity. It succeeded in spite of it.

Diversity, the world over, ruins nations. Somehow, These United States muddle through with an astonishing lack of contention and bloodshed. Will it last?