What Is a Man? Introducing the Idea of "Contest"

It takes little work to demonstrate that men are in trouble. The very idea of the "incel" cries out that something is wrong. To help understand this idea of "man" I turn to the writing of Walter Ong.

If there ever was such a thing as a self-evident truth, the current trouble in which men find themselves in our society today would qualify. Much ink has been spilt trying to figure out what is wrong with men folk these days. Rather than adding yet another piece to that discussion, I thought it would be more helpful to try to understand what a man is, what a woman is, and what makes them different. To facilitate this inquiry, I went back to a book I read once, way back in my undergraduate studies, some 30 years ago now, from a course in philosophical anthropology: Walter Ong’s “Fighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality and Consciousness.” Ong is, unfortunately, a writer who is criminally under read today. His insights would help inform many of the discussions we have in regards to the current state of things. Some of you may be familiar with Ong from his books, “Orality and Literacy” or “The Presence of the Word,” both of which are excellent at helping the reader understand the difference between an oral culture and one where writing and later the printing press has been introduced. Those two works are tremendously helpful in understanding the differences between ancient patterns of thinking and the ways in which we understand things today. This knowledge can be indispensable when interpreting the scriptures. In those works he tends to approach the subject by looking at the changes in human thinking and consciousness over time examining the effect the introduction of writing and later print. He does something similar here, but looks at how cultural changes over time have affected men, women and how they think and interrelate. Although he discusses both men and women, the question “What is a man?” seems to loom much larger throughout the work than that of “What is a woman?” for reasons that we become apparent as we work through Ong’s presentation. The key concept that he uses to unpack the nature of men and women and the differences between us is that of “contest.”

“Contest is a part of human life everywhere that human life is found. In war and in games, in work and in play, physically, intellectually and morally, human beings match themselves with or against one another.”

Ong argues that while contest can be hostile and combative, contests can also be used to sublimate and dissolve hostilities, building friendships and cooperation. Contest is part of a larger phenomenon that Ong labels “adversativeness.” The very idea that you are a human being, that you have integrity as a being, means that you are something while also at the same time not everything else. You are set off or set against your environment. You are distinct from everything else around you. Being set against something can be destructive, as when you collided with something else. Yet, this idea of of being set off and set against your environment can also be supportive. We have all had those terrifying dreams of falling and falling and falling. We never think much of the ground and the meaning of having our feet planted on the ground. The ground is in an “adversative” relationship to you, set against you. The friction between you and the ground keeps you in place.

So too, in order to know myself, I learn who I am in part by being set off from, or set against other persons. How am I different from or the same as this other person? How am I set off from them, or even set against them, psychologically or physically? To have an identity, you must have boundaries. One of the consequences of the drive within liberalism to always be breaking down barriers is that people lose their identity, their sense of self. They become an undifferentiated nothing with no existence at all. A big part of formation within community is that we learn the boundaries set for us. They are imposed on us. We find them. We push against them and even transgress them. But as these boundaries are established within us, and not just morality, but identity as well, they frame our sense of self, our behaviour. These boundaries are at first defined for us until they are interiorized and they shape everything from our sense of self to our behaviour. Without boundaries we are lost. We cannot establish ourselves, our identity or even how to behave. This is the danger of libertarian individualism. In a quest to be ourselves and establish ourselves without any involuntary influence from others, we end up with no identity at all. This puts us in the dangerous position of being vulnerable to whomever will tell us who we are. Today this is the propagandist. While community feels stifling with people always in your business telling you how to live your life, having this structure to push against actually allows you to better form yourself. Because of this, those who live in relatively well functioning real communities these days — such as growing up in an established church community — actually makes you more resistant — but not immune — to the influence of propaganda. Why? Because you have an identity formed in and through your adversative relationship with your community. It grounds you and sets the boundaries of who you are. This process shapes a real sense of self that cannot be easily undermined by the propagandist.

Ong makes the observation that we discover adversative pairings and adversative relationships everywhere, especially in philosophical and religious traditions. There is the pairing of Mother Earth and Father Sky. There is Yin and Yang. There is Li and Ch’i. There is Matter and Form. There is Thesis and Antithesis. There is also Male and Female. Even within the person, Carl Jung observed adversative pairings. One characteristic would be dominant, practiced and developed, while the other would remain primitive, unformed, the shadow side to the dominant characteristic. Jung noted pairings like Introvert and Extrovert. Sensate and Intuitive. Feeling and Thinking. Ong argues that the deepest truths are all found in paired opposites, seeming contradictions that exist side by side as valid. He makes the argument that total explicitness is impossible. And this is the rationalist conceit, that we can remove all contradictions through reasoned and scientific inquiry.

“The truly profound and meaningful principles and conclusions concerning matters of deep philosophical or cultural import are, I believe, invariably aphoristic and gnomic, and paradoxical. Their meaning is both clear and mysterious, and dialectically structured.”

The significance of this is that the deepest truths are revealed in and through the conflict of opposites. Many of the most profound truths are what Ong calls, “duplexes.” They are paired ideas that remain in tension and conflict. This has implications for knowledge itself:

“The dialectical structure of deep truth suggests why adversativeness has proved so crucial in the development of knowledge and of consciousness itself.”

He argues that this conflict, the contest, is at the heart of knowing itself. Contest can be lethal and hostile, but also, it can be life-giving. There is always a price to be paid with conflict and contest, but if we are willing to pay the price, the reward is that we can potentially come closer to grasping the truth as it is and not as we want it to be.

“Total explicitness, total clarity, total explanation is impossible.”

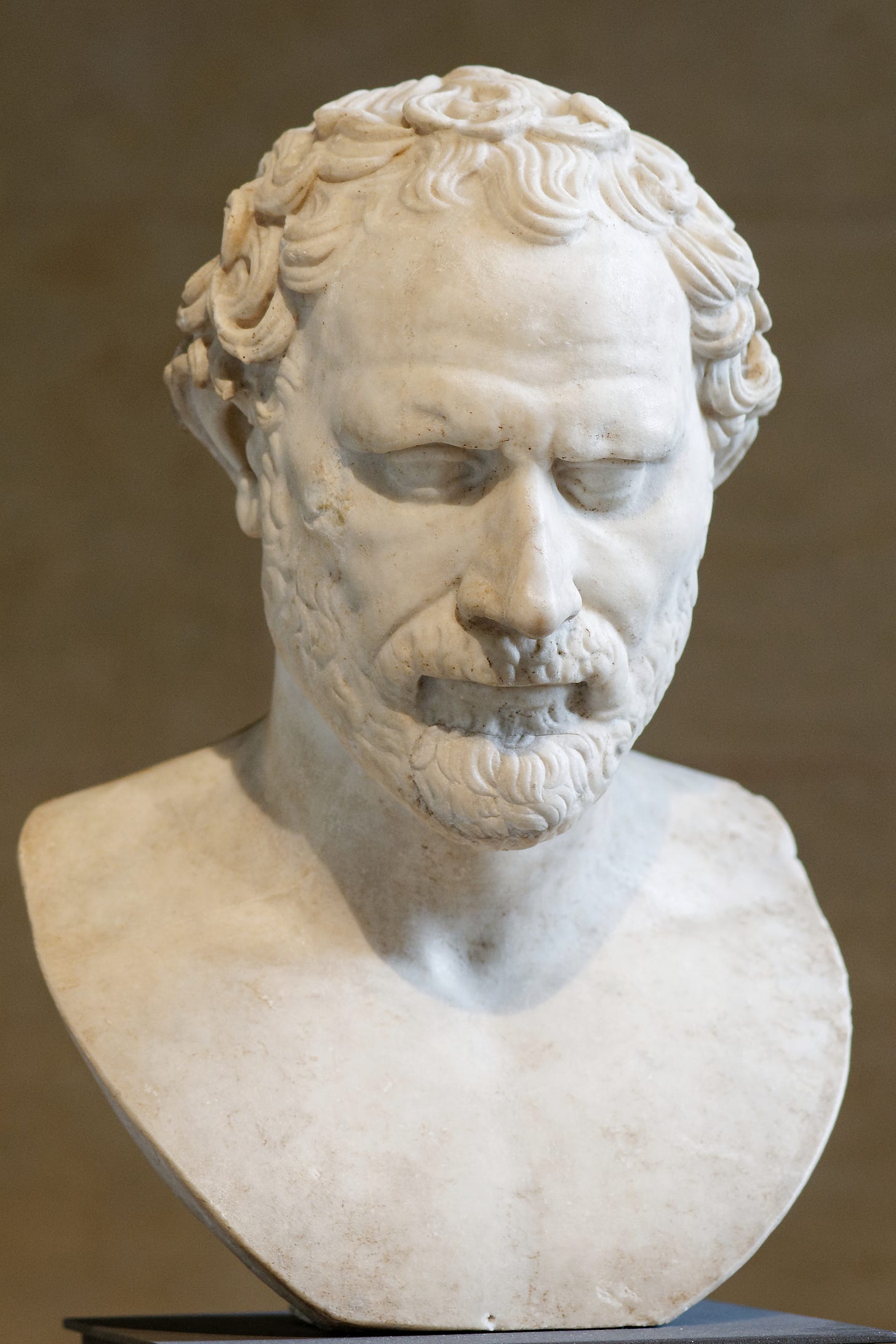

One of the central characteristics of Greek culture, Ong argues, a feature that that helped make it great, was that it placed struggle at the centre of their way of life. The quest for ἀρετή, excellence of any kind, and the glory and fame resulting from its achievement through personal action meant the setting of person against person, testing themselves against the adversary who could provide resistance and then overcoming it. Logic, one of the great achievements of the Greeks, a development which changed the world, did not appear in a context of dispassionate thought. Rather, it was developed out of a need for winning verbal arguments. Logic provided an iron clad means for besting ones opponent in an verbal intellectual contest. Chinese culture, while sophisticated, emphasized conformity over individual difference and personal excellence, and thus did not develop their own system of logic because it was not needed. Logic deals in setting up hard oppositions in which one argument defeats the other. More generalized rhetoric, on the other hand, deals in soft oppositions which are often open to negotiation. Both can be employed agonistically as necessary to win a contest. In contrast,

“Present day culture puts very little effort into deliberately creating and living out stress situations. We are unabashed irenicists, so unabashed that we have been unaware of how irenic we are by contrast with this earlier world.”

Ong attributes this shift from contest and conflict as an integral part of day-to-day life, to one in which we often strive to avoid conflict as much as possible, to the way that our culture has developed over time, especially in regards to the influence of writing and the printing press as well as the rise of the merchant class and the process of industrialization. Ong argues that the more oral a culture is, the more likely it will show a high degree of agonistic behaviors. With the introduction of writing, this makes reflexive thinking and logic possible. But because of its expense and the difficulty in producing written works, society still retains a high degree of oral adversativeness. Once the printing press is introduced and the printed word spreads widely, words can now be a private thing, interior, which as we will see, encourages a more feminine, irenic impulse. You see with the coming of print the introduction of things like “creative writing” where the goal is to express with words ones imaginative inner space. The more oral a culture, typically the more you will find agonistic behaviours. Writing, and then print, tend to push society to be more irenic. It is also not accidental that with the widespread introduction of the printed word there is also a concurrent growth in the female influence in society.

“The abandonment of ceremonial contest as a means (indeed, historically, a basic means) of transmitting conceptualized knowledge from one generation to the next is not unrelated to women’s liberation movements.”

Because of where we are situated in time and history, we tend not to notice this, but historically, speech has been one of the most conspicuous forms of conflict. From simple name calling and insults all the way up to highly reasoned oratory, one of the most prevalent forms of ritualized combat is found in verbal jousting. Speech itself is one of the primary forms of contest and conflict. Often the situations are highly ritualized or bound by social convention, but just because they do not draw blood, does not make them any less combative or adversative.

“In distant ages, speech, together with thought, was a highly combative activity, especially in more public manifestations — much more combative than we in our present day technological world are likely to assume or are even willing to believe.”

The notion of contest is built around the idea of aggression. Aggression is the movement from your space into the space of another. Most mammals have or maintain a buffer zone, a territory. They distance themselves from one another socially. Aggression is the act of moving into another’s territory, invading their space. Defense, while it may be vigorous and even violent cannot be aggressive because it does not initiate the action of moving into another’s territory. There are a number of good things that come from aggression. Constant, mutual acts of aggression create and establish the distribution of territory or space. Aggression, from a selection point of view, lends itself to sorting out the strongest, those who can successfully initiate the taking and holding of territory. Third, this acquisition and defense of space is part of the actions required for the defense of and provision for the young. That provision insures survival over the generations. Aggression is typically a male behaviour. It can also imply an insecurity, the need to take territory to assure safety.

On the other hand, the feminine absorbs the aggression of the male. The female occupies the space created by male aggression. She does this to establish a home and create a safe place for the raising of children. Male and female anatomy mirrors this dynamic. The act of procreation involves the woman taking male aggression into herself and embracing it for the conceiving of children. Ong highlights a Chinese proverb to illustrate the point:

“The female always overcomes because of her quietness.”

So what exactly is a “contest?” This word draws into itself a whole complex of terms including polemic, combat, fight, struggle, and competition. Contest is the binding that draws these related terms together.

“We can understand contest, in a way consonant with ordinary usage, as a struggle, earnest, possibly, but not necessarily lethal or even unfriendly, between sentient beings, conscious intelligent beings, entered into to determine dominance of one sort or another.”

This notion of dominance is key to understanding both contest and the generally male psyche. But a contest is not just any conflict. Etymologically, a contest is an agonistic situation between two persons in which a third person observes. This observation is important. The victory and the loss must be witnessed for a contest to obtain its true purpose. It was originally a legal thing, belonging to the realm of fairness in a environment controlled by rules, whether spoken or unspoken. It is a confrontation that strives for truth. It is trial by combat, even when the weapon is words. A contest is a witnessed struggle for dominance, witnessed by a conscious sentient being.

A contest cannot be computerized, for it is a thing which lives within human consciousness whose terms are known and understood but are not necessarily stated or explicated, nor can they be. They must be intuited. This is also why beating a computer game by yourself is never as satisfying as beating another human opponent and having that victory witnessed and acknowledged by a third party.

Conflict is what generates intellectual structures, the very structures of science itself. This constant pushing of the boundaries of what is known, pressing the contradictions within knowledge, establishes the boundaries, the space within which knowing happens. Fighting over this space creates it, determines it. The boundaries between schools of ideas. The exposing of flaws and contradictions. One set of arguments beating and overcoming another set of arguments.

When we as human beings enter into and take part in a contest, we do so, whether we want to or not, with the whole of our being. A half hearted effort, whether in winning or losing, has its effects upon us just as much as when consciously throw ourselves in fully. The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. This is the essence of the contest. There is a dread to having to answer that question, “How do you feel when you lose?”

Up next: “Boys Will Be Boys: The Making of a Man”

I really love the deep dives you do on authors. I feel like I get all of the key points and none of the fluff. Looking forward to the next Ong article

A tangent, if you'll permit me. You stated "To have an identity you must have boundaries." I have often wondered why God created the universe, but perhaps the answer is contained within the idea of (self-imposed) boundaries. God can only fully be God when there's "non-God" around. He is who He is, but it's a lot easier to be Yourself when You have something to compare Yourself to. Food for thought. Thanks for the article!