The Loss of ᾰ̓ρετή: Why Technology Makes You Dumber and Less Capable While Making You Feel More Powerful

We have this idea that because of technology we are becoming more and more powerful. In a way, as extensions of ourselves, it does do just that. But power is not the whole story.

Today we are surrounded by the amazing power of technology. It enables us to do, make and control things that would otherwise be beyond us. There is no denying this. As an extensions of ourselves, this great technical system within which we live brings us greater power by orders of magnitude. But this power comes with a price: the loss of our ᾰ̓ρετή (aretḗ). So what is this thing? It is a quality of character. If we had to boil the essence of the Greek culture as whole down to one word, it would be the pursuit of ᾰ̓ρετή. Liddell & Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon (yes, I own a copy) offers the following constellation of meanings:

goodness, excellence, especially of manly qualities, prowess, glorious deeds, wonders, miracles, moral virtue, good nature, kindness, productive, prosperity, reward of excellence, character, distinction, glory, fame, dignity, praise, good service.

We look to the Greeks as an inspiring model for high culture. The pursuit of manly virtues, art, poetry, drama, philosophy and even the sciences. They certainly seemed capable of making the leap from theory to practical technical application in order to produce the equivalent of the modern technological world. So why didn’t they? Jacques Ellul, in The Technological Society, says this, and I quote the whole section:

“In the fifth century B.C., Greece experienced rapid technical development, although later it came to an abrupt halt.

“In their golden age, the Greeks could have deduced the technical consequences of their scientific activity. But they did not wish to. Walter asks: ‘Did the Greeks, obsessed with harmony, check themselves at the very point at which inquiry ran the risk of going to excess and threatened to introduce a monstrosity into their civilization?’

“This was the result of a variety of factors, most of which were philosophical in nature. For one thing, theirs was a conception of life which scorned material needs and the improvement of practical life, discredited manual labor (because of the practice of slavery), held contemplation to be the goal of intellectual activity, refused the use of power, respected natural things. The Greeks were suspicious of technical activity because it represented an aspect of brute force and implied a want of moderation. Man, however his technical equipment, has from the very beginning played the role of sorcerer’s apprentice in relation to the machine. This feeling on the part of the Greeks was not a reflection of a primitive man’s fear in the face of something he does not understand (the explanation given today when certain persons take fright at our techniques). Rather, it was the result, perfectly mastered and perfectly measured, of a certain conception of life. It represented an apex of civilization and intelligence.

“Here we find the supreme Greek virtue, ἐγκράτεια (enkráteia) (self-control) [Liddell & Scott: mastery over, self-control, force oneself, master of oneself]. The rejection of technique was a deliberate, positive activity involving self-mastery, recognition of destiny, and the application of a given conception of life. Only the most modest techniques were permitted—those which would respond directly to material goods in such a way that these needs did not get the upper hand.

“In Greece a conscious effort was made to economize on means and to reduce the sphere of influence of technique. No one sought to apply scientific technically, because scientific thought corresponded to a certain conception of life, to wisdom. The great preoccupation of the Greeks was balance, harmony and moderation; hence they fiercely resisted the unrestrained force inherent in technique, and rejected it because of its potentialities. For these same reasons, magic had relatively little importance to the Greeks.”

As noted in the opening paragraph, there is no denying that technology is able to extend and magnify the power of mankind exponentially. The Greeks looked at this power potential and understood that it would destroy their whole conception of life based on human excellence and self-mastery. We in the West made the other choice. We embraced the power of technique in order to extend our ability to dominate the natural world, control it, and order it largely for the production of material prosperity. In this, we have been wildly successful. But the above quote implies that this power comes with a price tag: the loss of excellence and self-mastery. We gave up ᾰ̓ρετή and ἐγκράτεια for the dynamism of the machine.

You might be asking yourself, “Does this have to be the case? Is this really an either-or choice?” There are some things that machines can do that people cannot. You cannot make a steam engine without having first having a metal cylinder that is smooth and round beyond the capabilities of what a human can manage with hand tools. You need a lathe. To make the inside of a metal cylinder round and smooth enough to create an adequate seal with a piston, you have to be able to machine it to tolerances which a person cannot manage on their own. Here the lathe expands the capabilities of human beings to build things they would not be otherwise able and enable them to harness forces that they otherwise could not. There are many such examples like this where machines, where technique, extends man’s power and capabilities.

Human beings have been tool users for as long as we have a historical record. We have always had technique with us. To use a tool properly, you must become skilled in its use. Was there a difference in the way tools were used the preindustrial period? Yes. For one, there were far fewer tools. Today, if you have a task in mind, there is probably a tool designed specifically for that application. In the past, you had a handful of tools, some of which you made yourself, and these few tools were used for a wide range of circumstances. Although the tool was necessary, the most important thing was the skill of the craftsman. The value was not in the tool but in the mastery with which the person demonstrated in their use of the tool. Even the language used to talk about the use of tools underscored this. You had master carpenters. Master stone masons. Master tailors. Mastery was valuable and elevated you as a person. A “master” was of greater status than the “journeyman” who was not yet a “master.” The “apprentice” was not yet a “journeyman.”

Much of the knowledge surrounding the use of these tools was closely guarded within villages, within guilds, within families. The knowledge was embedded within the life of the person and the collective culture of the community. It would be passed down orally and through careful demonstration and correction. You learned the techniques, but they were not abstracted from the environment in which they lived. Technique and tools would vary slightly from place to place. You would find a particular tool used in one place, but not another. There they might use a different tool to accomplish the same task. The important thing was not the tool per se, but the skill, craftsmanship and wisdom of those who used the tools.

This same theme applied itself across society. We have laws, regulations and detailed policy manuals which try to account for every possible situation. Before the rise of technique, many of the laws and rules of society were simple enough that most people had the essence of their society’s legal code in their memory. Embedded, organic rules existed, but this simple code would guide decisions across a wide range of situations. They did not need to consult a policy manual. They used their own wisdom and if that failed them, there was always the village wise man, or woman, or the counsel of elders.

With the rise of technical society, all processes get subjected to rationalization and abstraction. This happens in a number of ways, and for multiple reasons. One is variability. Another is efficiency, which is also related to productivity. As the technical mindset takes root in society, it is constantly questing to find the one best way to do everything. This is the “best practices” approach to everything. We must find or establish the “best practice” in our business, in our organization; that is, the one, single, best way to do anything.

At one time, while crafting furniture you would flatten a tabletop, applying your skill using these tools:

Today the skills associated with this kind of woodwork are often done using these kinds of machines:

All the skill of the craftsman has been passed off to a very powerful, efficient machine. But what happens to the abilities of the wood worker? It withers as the power of the machine grows.

So how do we arrive at such a thing? Every skill, every task, every process must be broken down into its constitutive parts, studied and then developed into a rationalized system. This is the essence of Frederick Taylor’s “time and motion” studies. The idea is that once the task has been rationalized and turned into a reproducible process, you can then train people into the process and produce consistent repeatable outcomes, regardless of the person plugged into the system. The important thing is the “system” or the “method” or the “process.” The person becomes irrelevant. Anyone can do it with enough training.

What is the difference between this and the old way? The process exists outside of and separate from the person. It is its own thing. It is abstract, rational and portable into any situation. You can make anyone a competent teacher if they just follow the prescribed methodologies. You can produce consistent outcomes. You can make anyone good at customer service, or sales, or management. Your company can use the right management processes and can be a well run company. The emphasis is on the processes and not the people. The people can be directed and managed by the right policies. They can be augmented and replaced by machines which can be designed and programed to do the same tasks. Human skill, inventiveness, creativity, knowledge is passed off to policies, methods and machines. In this way we can produce more consistent outcomes. We can do so with greater control and efficiency. Machines can keep going when people would tire and begin making mistakes. We can increase productivity.

Little by little, all throughout society, tasks are increasingly passed off to machines. Spell check and Grammarly may improve the end product of your writing, but are they making you a better writer? Are you learning and interiorizing the skill of writing? AI writing aids may make your writing more consistently better, but are they improving your skills as a writer? A spread sheet may allow you to make complex calculations quickly and accurately for larger data sets. They may increase the power of your work output. But are they increasing your skill at doing mathematical calculations? The more you rely on the machines, on techniques, on methodologies and on policy manuals, the more you undermine and erode your ability to do the same tasks. You may produce more consistent outcomes, more efficiently and thus increase power and productivity, but you do so at the price of your diminished skills as a human being.

We as a society are now wrapped in technique such that we interact with reality less and less. Technology and technical, systematic methodologies encompass all that we do today such that it is very difficult for us to relate to the world directly without that experience being mediated to us through technique and technology. Heidegger called this “enframing.” We can not longer spell. We can no longer make things with our hands. We cannot give a customer a refund, because our manager is not here and the computer will not allow us to do that. We must check the policy manual. We value “good process” over “results.” Nobody thinks for themselves. Events are not real unless we see them on the news. We cannot do or decide something without first consulting the “experts.” We must be monitored in all that we do, for “quality control” and “training purposes.” Everything is mediated to us through the technical system. We do not allow ourselves to experience unmediated reality. We no longer have direct contact with reality. In many cases we don’t even touch the machines. We certainly never touch the materials being processed by the machines. You can’t get in touch with decision makers. You must navigate a bureaucratic maze of policy and structures. But before that you must take your chances navigating the dreaded “phone tree.” Or you can take a chance with the AI customer service bot on their website and hope that real service will happen as a result.

In this reality, more and more of us live and work within these systems and we increasingly become looked upon as replaceable cogs in a grand machine. Even the “professions” are becoming affected. We can import people and plug them into any kind of work as long as they follow “the system.” We can replace people with machines. People get reduced to being nothing more than “hands.” The more that “value added” is moved from people to machines and systems, the more replaceable, redundant and less valuable they become. Highly skilled people with well guarded, embedded organic knowledge have power and are valuable and can command both social standing and compensation commensurate with that skill. As skill is passed off to machines and methodologies, the person loses power and value. The value is in the device. The power is in the technique. The person? Replaceable and valueless. Work has value when it demand competency and skill. Work enframed within the technical system means turning yourself into part of the machine, alienating yourself from your own potential as a human being in return for a pay cheque, living with the anxiety that you might just be replaced with the next round of technical or methodological improvements. At times it seems that only with our hobbies are we allowed any contact at all with tangible reality.

Recently, AI optimist and advocate Marc Andreesen put out this piece:

He makes some interesting claims in his piece First is that we are “teaching” computers. He seems to know better, but it is interesting that he begins by anthropomorphizing these powerful computers. You can program them with sophisticated algorithms. You can provided them with massive quantities of data, but they do not themselves “learn.” This is important to remember. These are powerful tools but the computers themselves are not sentient and they are not, as a result, “learning.” I write more on this here:

Andreesen leans into the idea that machines are merely tools which always extend the power of mankind. He argues that smarter people have better outcomes in almost every domain of activity. I don’t disagree with this. He asserts that we have leveraged that intelligence through machines to raise our standard of living. There is no denying this as well. This is the great argument for technical society. And he then asserts that these algorithms have the potential to further magnify these positive outcomes. That may be true. He argues that these large data algorithms will be nearly ubiquitous. We will see algorithmic teachers, assistants, collaborators and these will increase productivity and prosperity across the board. One does wonder though, what will happen to all of the human assistants, teachers and collaborators? One gets the sense that this is a technology which Marc Andreesen sees as being very good for Marc Andreesen and people like him. One also suspects he has not fully thought through the effect that these machines will have on many others.

He then boils down the essential lure of technology:

“Anything that people do with their natural intelligence today can be done much better with AI.”

Looking above to all the tasks that used to require tremendous human skill to accomplish, which are now being done faster and more efficiently with machines, or producing more consistent results through the abstraction and systemization of techniques, it seems that Andreesen is making the argument that we as human beings should be willing to pass the last few remaining skills we possess ourselves off to the algorithms and that this will increase our power as human beings.

“Perhaps the most underestimated quality of AI is how humanizing it can be.”

This, to me, is just frightening. We are going to abstract every last human skill you have and pass them off to algorithms which are trained to look and feel like human beings, and you will thus feel like your humanity is being enhanced? Call me skeptical.

“It is a moral obligation that we have to ourselves.”

Any objection you might have is just “backwards” moral panic. This is the future of progress, of human evolution. Andreesen then proceeds to raise and knock down numerous objections, one of which is that people fear these algorithms because they fear it will take their jobs. It will. But Andreesen recycles the same arguments that people have been using since the advent of globalization, the offshoring of production and the influx of cheap immigrant labor, that it will create jobs! Your incomes will all go up! Again, call me skeptical at the idea that passing off ever more human skill to machines will increase our material value to employers and society. In the end, he argues that we must do this things as fast as possible because our enemies are doing the same. We need more! We need it faster!

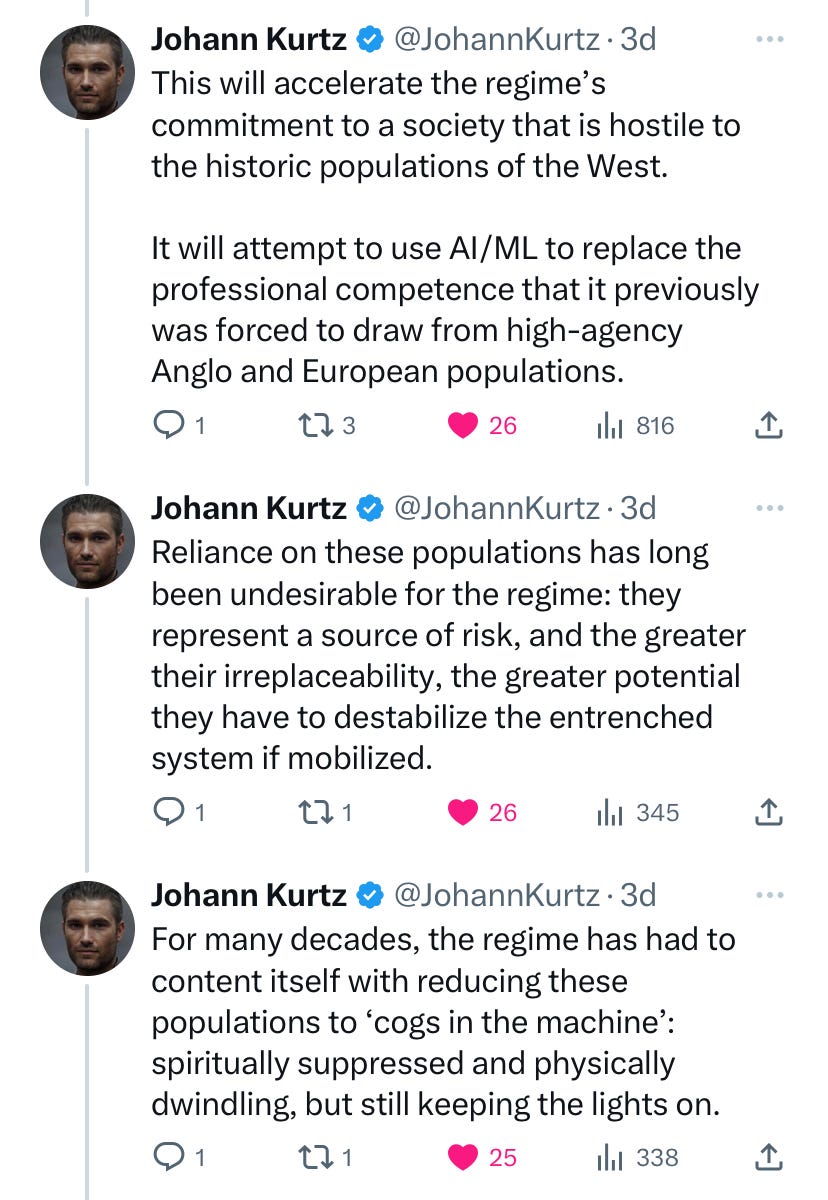

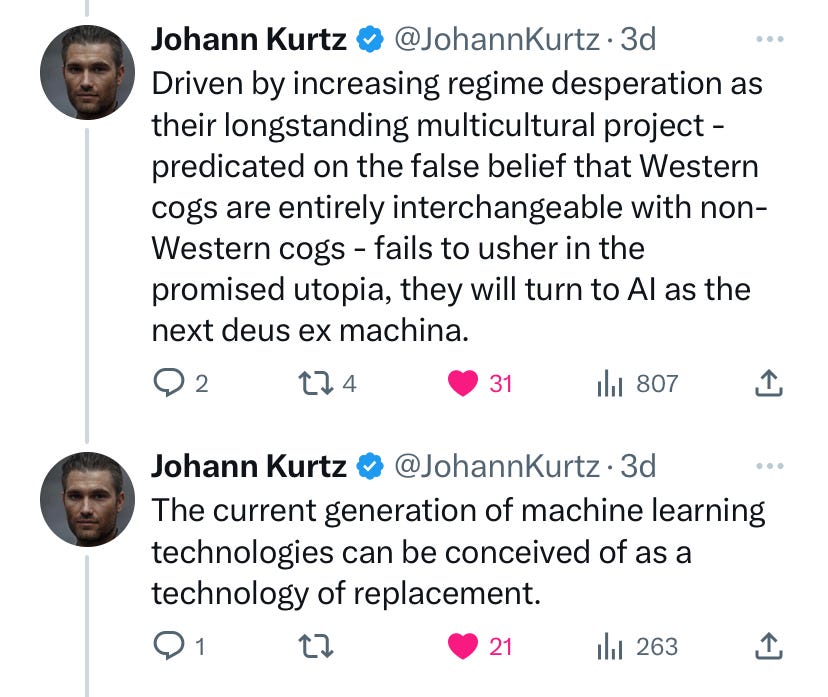

Johann Kurtz of the Substack “Becoming Noble” recently wrote a Twitter thread responding to Andreesen’s claims about so-called artificial intelligence technology, within which he makes the following argument:

When I saw this thread, I right away knew that I was on the right track with the arguments I have been making. Johann makes the point that highly skilled people are a destabilizing threat to any regime. They organize into guilds and associations which have real political power. They can oppose the regime. They can make demands of the regime. They can direct its policies in ways that the regime itself would not choose. Technology represents a real political assault upon the skilled labor classes, reducing their own power in favor of those who own and employ the machines, techniques and methodologies. If there is real power and value in a skill, then there is also real power in owning abstracted techniques: that is, in what is known as “intellectual property.” Power is transferred from the skilled classes, abstracted, turned into “property” that is then employed against the people, turning them into replaceable cogs without power or agency.

With the advent of AI technologies, the real possibility exists for a whole host of tasks and processes, those formerly in the possession of professionals of various kinds, that will now be abstracted, systematized, and turned into digital assistants for the few remaining people with real intellectual value. As Kurtz argues, contra the assertion of Andreesen, the regime has always coveted the idea of being able to replace workers with machines. Machines are powerful. They are run tirelessly 24/7, and they are not politically risky.

And then, if you are thinking that the regime really can’t be trying to rid themselves of vast swaths of humanity, up steps Yuval Noah Harari and the World Economic Forum with this piece:

Harari and the WEF seem to channel the regime’s id, its generally powerful but unspoken desires. They seem a cartoonish bunch, but Harari is obviously smart, even if his ideas are clownish. But he does tap into a current that has run deep and long among the bourgeoisie elites in regards to the problematic nature of much of the blue and white collar working classes:

“Harari gloated last year that “we just don’t need the vast majority of the population” in today’s world.

According to Harari, most of the general public has now become “redundant” and will be of little use to the global elite in the future.

Harari argues that modern technologies like artificial intelligence “make it possible to replace the people.”

“If you go back to the middle of the 20th century — and it doesn’t matter if you’re in the United States with Roosevelt, or if you’re in Germany with Hitler, or even in the USSR with Stalin — and you think about building the future, then your building materials are those millions of people who are working hard in the factories, in the farms, the soldiers,” Harari said.

“You need them.

“Now, fast forward to the early 21st century when we just don’t need the vast majority of the population,” he added.”

Our elites understand implicitly the point and purpose of much of technology. For the average man they are billed as cool toys or for our convenience. They tickle us with their novelty and their power. Faster. Bigger. More powerful. But they all, in little or small ways, give us some something, while at the same time taking something from us as well. The “something” is often tied up to our ᾰ̓ρετή.

So what do we do? Is there a way for us to reclaim our excellence? It does seem that we are facing a decision point in regards to our humanity. We have to ask ourselves, what is our goal as human beings? Is it to increase our power at all costs? Because, if that is the case, then the full spectrum of technique is the speed run for extending our power. The price we pay for that power, though, is our gradually reduced capacity as human beings.

If on the other hand, we wish human beings as human beings to flourish, if we want to maximize our human capacity, we need to say “No” to technique. At the very least, we should be judicious in its use. Do we have to go the route of the Greeks? When push comes to shove, the answer to that is most likely a resounding, “Yes.”

I think this is something which Tolkien saw as well. The “ring of power” and the two towers of Mordor and Isengard encapsulate the human drive for knowledge and power. The power to control and dominate. The power of technique and the machine. There are two paths that one can walk. One can grasp at the power of the ring and it will consume you. You could be Isiledur, Boromir or Gollum. Or, worse, you could be one of the Nazgul, the Ring Wraiths. Hollowed out by power. Are we a society of ring wraiths?

So how can I reclaim my own ᾰ̓ρετή? How can we as a people?

It is hard on one’s own. But as we have talked about in other pieces, the path forward is to create a space within a parallel community, which I argue should be the community of Christian believers, which represents a clear contrast to the world around us. When we go out into the world, it may be a place of technique and machine. But within the church community we can be not only a place of rest, but also a place where people can reclaim their humanity, their excellence, their agency. We can cultivate mastery and skill in as many areas as possible. A people who cultivate ᾰ̓ρετή through the exercise of ἐγκρᾰ́τειᾰ are a people to be feared, a people of power and strength.

In Paul’s letter to the Philippian church, he makes these remarks, urging people to be Christ like in their manner and conduct:

5 In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

6 Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

7 rather, he emptied himself

by taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

8 And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross! Philippians 2:5-8

That word “emptied” — kenosis, κένωσις — is of profound relevance to this discussion. The problem of technique robbing us of our excellence, making us like ring wraiths, is that in so doing it has stolen from us the ability to empty ourselves, to sacrifice ourselves for others. Jesus, when he came, emptied himself of his power and glory, his excellence, so as to sacrifice himself for us. But for us to be able to imitate Christ, we must first have something to sacrifice. And far too often we are empty shells, hollowed out by machine culture.

But we also know too that the way back for us is not a path of self-salvation. We begin with the grace of God. He has promised to us his Spirit, his power. All we have to ask:

13 “If you then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!” Luke 11:13

But what God gives, we need to embrace and make our own. We need to cultivate, not just spiritual mastery, but mastery across the fullness of our humanity. You may never be asked to make that kind of sacrifice. Yours might be smaller. But either way, how can you sacrifice what you do not have. And why would you give it away, hollowing yourself out, for some false promise, some false bargain? This is a big part of the of the role of the church community, to live lives that by their very living, exposes the poverty of the world, its emptiness. This is the kind of resistance that the regime truly fears.

Nice post. The pursuit of technology is a catch 22, like most things in life. A blind focus on technological progress provides power advantages over others, therefore all nations and leaders pursue it; but it comes with it a loss of humanity, a loss of individual privacy and control and freedom and birthrates, the decline of mankind down to that of a widgit, to be used and discarded by the establishment at their will.

Serious religious communities like the Amish, Orthodox Jews, and seriously religious Muslims are much more resistant to these processes as reflected by their much higher birthrates (Mormon birthrates are plummeting as they succumb to globohomo; it seems like all other Christian communities have declining birthrates as well...), but their natural growth rates are swamped by vastly increased illegal immigration rates.

The question of whether or not technology could be harnessed to improve humanity instead of improve the power of elites is an interesting one; it would certainly take a different kind of elites, ones with noblesse oblige instead of noblesse malice and ones with time horizons and motivations beyond just their continued control and punishment of the masses, if it is possible at all...

I enjoy your section on writing aids. Hemingway is a nice tool but I hate how it neuters my writing style, voice, and rhetoric.

This thought process is also a massive theme in the Dune series. Developing the power of the human mind vs. handing it off to a machine.