The Floundering Church: Trying to Be Something It Is Not

Many have tried to tackle the question of why the Christian church dwindled in the modern age. One answer is that perhaps it is trying to become "modern," but modernity does modern better.

There are many theories and explanations for why church attendance and the importance of Christianity in western society has been falling off now for some time. There is even a whole field called “secularization studies,” or something like that. People chalk it up to our relative prosperity. Some would point to the disastrous effects that industrialization and urbanization have had on the family. Others point to the corrosive philosophical ideas promulgated since the beginning of the modern era. All of them have merit and do add something to the discussion. But I am increasingly becoming convinced that the waning influence of the church and of the Christian faith is due in part, perhaps in large part, to the same reason we don’t have kings and noblemen anymore. They just weren’t “effective” enough in a world that values material effectiveness above all else. “Does it work? And if it doesn’t work, give me what will.”

What got me thinking about this was a quote from Carl Schmitt’s The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy. I actually first came across this passage before reading the book in an article titled, “Farewell to Bourgeois Kings.” by Malcom Kyeyune on his old WordPress blog:

“In the history of political ideas, there are epochs of great energy and times becalmed, times of motionless status quo. Thus the epoch of monarchy is at an end when a sense of the principle of kingship, of honor, has been lost, if bourgeois kings appear who seek to prove their usefulness and utility instead of their devotion and honor. The external apparatus of monarchical institutions can remain standing very much longer after that. But in spite of it monarchy’s hour has tolled. The convictions inherent in this and no other institution then appear antiquated; practical justifications for it will not be lacking, but it is only an empirical question whether men or organizations come forward who can prove themselves just as useful or even more so than these kings and through this simple fact brush aside monarchy. The same holds true of the ‘social-technical’ justifications for parliament. If parliament should change from an institution of evident truth into simply practical-technical means, then it only has to be shown … through some kind of experience, not even an open self-declared dictatorship, that things could be otherwise, parliament is then finished.”

You will find the first half of the above paragraph in Kyeyune’s article. The rest is from Crisis and fills out the quote somewhat and further extends the same principle to the very parliamentary democracy that replaced monarchical institutions.

So what is going on here? What is the point that Schmitt is trying to make?

His argument is that a mode of governance rests on a justifying narrative. This narrative explains both why we need a certain governance model and why the rule of the people who populate those structures is legitimate. The rule of kings and nobles was based on the embrace of an underlying cosmology. The king was put where he was by God and his rule helped support and maintain the order of God in society. Kyeyune details the concern that was taken over whether the king in certain situations was acting as an ordinary human or whether he was representing the metaphysical order. The difference mattered in evaluating the legitimacy of the actions of the king. This whole metaphysical architecture was supported by vows of loyalty and mutual obligation that were in turn underpinned by one’s honor before God and man. This metaphysical and moral order held society together and provided its logic while it also devalued other things. While wealth was important, one’s honor was more important. Loyalty and maintaining one’s oaths was of higher worth than how effective an administrator you may or may not be.

But if those metaphysical underpinnings shift or change, they will change with it the legitimating story for governance and leadership. When “effectiveness” comes to be valued more than honor, it justifies a power structure where the effective rise above the honorable. If those who had occupied positions of leadership based on the previous metaphysical arrangement try to pivot and themselves become effective, they have, argues Schmitt, written their own death sentence as a ruling elite. If utility, efficiency and effectiveness are the criteria used to define the elite class, then the leadership structure itself will begin to favor this new underlying justification for rule. The guy who is most suited to rule is the person who can get things done. It does not matter that he is a complete snake. He is effective.

Yet, as Schmitt notes, the argument for honor in politics has persisted. “We want people of character to lead us,” we are told. Yet, at the same time, people trumpet the meritocracy as the best way to determine who should rule us. We want the smartest, the brightest and the most accomplished people as our leaders. What this tells you is that no one really cares about their honor or character. Effectiveness is all. This is a big reason why no one cares much anymore about the morality of politicians. All that matters is that they deliver. Deliver on their promises. Deliver on their agenda. Deliver patronage to their supporters. Deliver power to the party. They need to be effective. Morality has nothing to do with how effective they are. If they perform, even if they do nothing more than help keep the ruling party in power, they will likely get a second chance if tripped up by their moral failings.

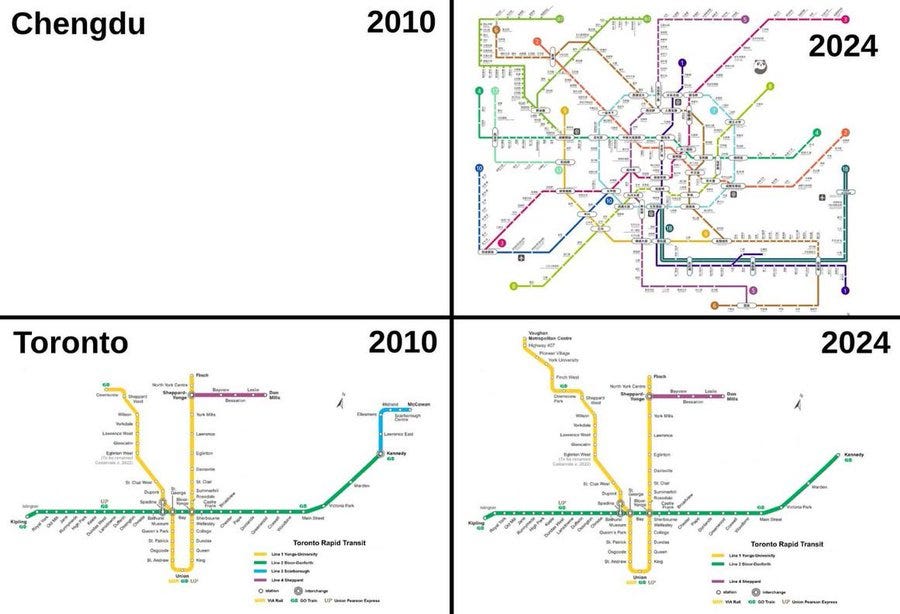

Schmitt applies this to parliamentary democracy itself, which, he argues, is based on the free exchange of ideas in an open forum where the pursuit of truth is the aim. The “marketplace of ideas,” as instantiated in the legislative body, is supposed to allow the best ideas to come to the surface and form the laws of the nation. But if all we care about is “effectiveness,” why are we so worried about democracy and its pursuit of the truth. It is a cumbersome and inefficient means of governance. Why not simply dispense with the all the democratic inefficiencies and just let elite managers run the system with a free hand, employing the latest managerial technologies? This is why you see “elite human capital” types regularly pointing at China and its effectiveness, generally in contrast to our ineffective legislative and bureaucratic systems here in our democratic nations. This example showed up in my feed the other day, highlighting Toronto’s inability to build subway systems in contrast with the Chinese city of Chengdu:

As Schmitt notes above, once the people clue in that the governing system would likely be far more effective with a strong, singular executive, assuming they value effectiveness above all other criteria, the likely path forward is towards either a dictator or perhaps simply the managers just cut the legislature and the executive branches of government out all together. This is essentially what has happened in the European Union.

We saw this whole paradigm play itself out in the last year. Justin Trudeau was no longer seen by his elite backers as able to deliver effective governance for them. His ideas were too ideological, too wrong for the present moment, and, frankly, he was just too much of a clown to be taken seriously by anyone anymore. What they needed was an effective manager, someone who could right the ship. Who better than an elite manager’s elite manger: Mark Carney, former head of the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, as well as the head of Brookfield Asset Management. After a few months of propaganda doing glowing puff pieces on him, Justin Trudeau suddenly resigned and Mark Carney was “elected” — installed — as the leader of the Liberal Party of Canada. Now he is Canada’s Prime Minister, expected to effectively produce a more prosperous Canada that will strengthen the position of his elite backers. Democracy doesn’t matter. One of his first acts was to prorogued parliament so as to give himself more freedom to effectively consolidate power and act unilaterally without parliament slowing things down.

What does all of this have to do with the Christian faith and the strength of the church? The underlying foundations of Christianity are not based on its material effectiveness. The Christian faith about the means and process of reconciling people to God. Because of sin, we have been cut off from God and cast out of his presence. When once we used to walk with God in the cool of the morning in the Garden of Eden, now, merely to be in the presence of God puts your life in danger. The Christian faith is about restoring and maintaining a right relationship with God, what is known as “righteousness.” Wrapped up in this process of restoration of right relationship is “justice.” Justice is the process of restoring a right relationship once it has been disrupted. Also related to this is the state of holiness that can be cultivated once one is in a right relationship with God. It is a separateness, a drawing away from that which is merely “clean” and “right,” into a state of purity and union with God, where one occupies a space that is in the very presence of God himself. You enter into the Holy of Holies, so to speak.

This notion of “righteousness,” when it is the dominant value in society, supersedes all other concerns. Wealth and power find their meaning when they are in a subordinate relationship to righteousness. What is most important is that a society is right with God. That tax and trade policy is right with God is far more important that whether or not it is effective in building wealth for the members of society.

Alongside of this there is the notion of judgement. Christ was going to return and God would, through his Son Jesus, judge the nations and their peoples for the things they have done. God would hold the unrighteous and unjust rulers to account on the Day of Judgement.

Additionally, the Gospel, the Good News, functioned to offer consolation in the midst of a world scarred by sin and evil, a world where the unrighteous prosper and the unjust grow wealthy and powerful. God would notice the humble. And when the wealthy elites forgot that their wealth and power was meant to serve righteousness and justice, it would be God that would hold them to account on the Day of Judgement. You could cry out to him in lament knowing he would hear you. The message of the prophets was one part warning, another part consolation. Yes, God is promising that the wicked rulers would pay for the injustices they have committed. The judgements of the Revelation of John are meant to give you hope, to console you, to let you know that the wicked will suffer for what they have done before God. Especially those who hold positions of power and wealth.

But what happens when people stop believing that Jesus is going to return, or they just pay lip service to the idea? Modernity is what happens.

It is not the kind of thing that happens over night. No one flipped a switch. But little-by-little most people stopped focusing on the world to come. With the rise of the merchant class in Europe beginning in the 1400’s, maybe earlier, society became more wealthy and prosperous. New new methods of learning began to take hold. People came to believe that they could effect real change within the confines of history. The divine narrative of God’s second coming and the Kingdom of God began to be historicized, brought down into the realms of history. Through the excess wealth we have generated by our effectiveness we we could end poverty. Through science and medicine we could end disease. Through the application of reason to public affairs we could engineer a society without problems. Human Progress will make this all possible. What we need to do is bring together our best and brightest, our most effective people, and we can make this all happen.

What happened to the Christian faith in this environment? Like the medieval kings who were being pushed aside by the effectiveness of the merchant classes and tried to hold on to power by competing with them in the realm of effectiveness, this is essentially what Christianity has tried to do during the same period. For example, today we worry a lot about the effectiveness of prayer. The question of whether or not “Does God answer prayer?” hangs over the church. What does this mean? Is prayer, is God, as effective at bringing healing as are the doctors and the medical system? The efficacy of prayer has always been a question, but when you read the scriptures and the church fathers, its not something that jumps out at you as real concern for them. Prayer was primarily about drawing close to God. Even a passage like James 5:16 gets nudged in its interpretation by modern “effectiveness” thinking, as here in the NIV:

“The prayer of a righteous man is powerful and effective.”

The word translated as “effective” — ἐνεργουμένη, energoumenē — carries the idea of energy and activity, to be an active power, earnest, and in this sense it can be effective. This idea that there is energy and power in prayer does not necessarily mean that it will “get things done” or “it delivers” in the modern sense of “that is an effective method.” This way of thinking pushes prayer into a model where it becomes little more than just one of many technologies, judged solely on its ability to deliver results. If I go to the doctor and get the treatments he proscribes, they bring results. Soon, all we do is pray for the doctor or the surgeon. All our expectations are with the doctor and his effective methods. But the older idea of drawing yourself into the energy and activity of God gets lost in this need to produce the effective material results we desire and expect. Not that God can’t heal you or that he won’t. It is not that prayer isn’t powerful. It just that it is not a technique or a machine that spits out the desired results on command. And so, people begin to lose faith, even when they keep the language of prayer because it lacks the “effectiveness” they are told to expect from everything else in the modern world. They book an appointment their doctor long before they call the elders to anoint them with oil and pray over them.

When it comes to morality, in the hands of Kant, Christianity was stripped of all its metaphysical and superstitious elements and a self-evident rational morality was distilled so as to be effectively applied to our lives and society without needing all the harmful passions that religion brings. We can make justice more effective through the development of sound governmental policy. The church can be the means to help give you a happy, prosperous and effective life. Live your best life with Jesus at your side. We can use effective means of management to grow the churches, glossing these methods and techniques over with a thin veneer of God language and the formalities of prayer. But it is a constant uphill battle for the church and the Christian faith to deliver to people the material good life that modernity promises them. Modernity tells them that it can effectively satisfy all their needs materially. You don’t need all that church stuff. If you want to do that and think it helps you, then you do you. I mean if you find it effective, who am I to judge? Right? The more that Christians try to answer modernity on its own ground, the more it seems we diminish ourselves. We are like the kings of old trying to adapt to the new legitimating narrative of “effectiveness.”

One of my great fears with the new political resurgence of Protestant Christianity is not that the Christian faith doesn’t have political implications or that it shouldn’t involve itself in the political. It absolutely should and can’t avoid doing so. What I worry about is that Christians will try to do it along the vector of “effectiveness.” “Christian teaching is the most effective formula for governing the nation.” Once someone says this, or something like it, they have already lost because they are no longer trying to govern in the terms set by the Christian faith, where righteousness supersedes all other values, even effectiveness. Instead, they are trying to be more effective than modern liberal technocrats. I mean, you might succeed. But at what cost? The point of the Christian faith is not its “effectiveness” as understood in modern terms. If you bristle when someone tells you, “The Christian faith is not supposed to be effective,” then you are not thinking like a Christian. You are thinking like a modern technocrat.

We are at an interesting juncture. People are beginning to flock back to the church in places once thought to be so thoroughly secular as to be virtually pagan societies, such as France. What is happening? Well, modernity is slowly, and maybe not so slowly, starting to show cracks in its veneer of effectiveness. The period of Covid lockdowns in the early 2020’s was eye opening for many. It pierced the veil and exposed many leaders as ineffective and clueless, yet nonetheless willing to use coercive power to cover up their own ineptitude. The younger generations are noticing that they are not able to achieve the same levels of prosperity that their parents and grandparents enjoyed and likely never will. Dating is a right mess, let alone the possibility of family formation. The Global American Empire is no longer able to effectively assert its power over the globe the way it could even 20 years ago. On and on examples could be given. So what happens when people lose confidence in the effectiveness of modernity? What happens when the future looks increasingly grim? Even if they don’t know what they are looking for, people begin to look for consolation.

As we just discussed, this is part of the old ordering principles of the Christian faith. We cannot guarantee that we will make you more happy and prosperous. But we can give you peace in the life you do have by showing you how to draw close to God:

“Q & A 1

Q. What is your only comfort

in life and in death?A. That I am not my own,

but belong—body and soul,

in life and in death—to my faithful Savior, Jesus Christ.

He has fully paid for all my sins with his precious blood,

and has set me free from the tyranny of the devil.

He also watches over me in such a way

that not a hair can fall from my head

without the will of my Father in heaven;

in fact, all things must work together for my salvation.Because I belong to him,

Christ, by his Holy Spirit,

assures me of eternal life

and makes me wholeheartedly willing and ready

from now on to live for him.Q & A 2

Q. What must you know to

live and die in the joy of this comfort?A. Three things:

first, how great my sin and misery are;

second, how I am set free from all my sins and misery;

third, how I am to thank God for such deliverance.”

For those that don’t recognize these words, they open the Heidelberg Catechism.

Our task as Christians is not to try to out modern modernity. That has been a loser for us. The wreckage of those efforts are all around us. But we can bring consolation. We can help people draw closer to God in faith. And we can point them to the Day of Judgement when God will make all things right in Christ. It is not about effectively growing churches or establishing the perfect political order or even the most rationally perfect theology. It is about ministering the grace of God, that in Christ you can be right with God and reverse the alienation of being cast out of God’s presence. No matter what else is happening in the world around you, you can begin at this point, at the comfort you can experience by being made right with God in a world of misery, in a world that stands under the judgement of God. You can have the peace that passes all understanding.