Ruled by Men or Governed by the System?

We are locked within the tyranny of the administrative state, governed by the administrative system. What is the alternative? It is to once again be ruled directly by men.

Once you begin to seriously question the administrative state in its various forms and manifestations, people will ask the obvious question, “If not this, then what?” Let’s take a stab at an answer. To do this, we must first understand exactly what the administrative state is at its core. This thing is not any of the existing structures, that is, the bureaucracies in their various forms. These are mere artifacts. The administrative state is, at its heart, a way of thinking about the world that manifests itself in these structures to which we attach the label: “the administrative state.” The problem is not bureaucracy per se. All empires have bureaucracies of some form or another. What makes the modern administrative state as we know it and encounter it in government, business and non-profits, the thing that it is, is the way that the people who establish, structure, build, utilize and reform these institutions think about the world and the problems it presents. “Technique” is the word that Jacque Ellul used to describe this way of thinking in order to distinguish it from the machines and systems themselves. Those are the artifacts created by this way of thinking.

What defines this pattern of thought? Its two main characteristics are “abstraction” and “rationalization.” Abstraction is that process whereby you take something that is rooted in the physical, experienced within the culture and spirit of a community, its living history and social dynamics, and you then examine it, break it down into its constituent parts and analyze it, turning it into something that is conceptual. The rationalization process then takes the next step and is able to refine this set of abstract concepts into a system that can be worked on, discussed, argued over without ever having to actually the do the thing which is being discussed. Something which was once intuitive, organic, grounded in what is real, is now a thing of language and numbers. This abstract, rationalized process can then in theory be transported through time and space and applied in any situation regardless of persons or culture.

Abstracted, rationalized processes can be combined with other rationalized, abstracted processes in ways that grounded, culturally embedded, organic processes often cannot. Processes and tasks can be broken down, recombined in new ways that potentially makes them more efficient. Once a task is broken down and rationalized it can also be mechanized. A task that is sufficiently rationalized can also be made to produce consistent results regardless of the person. Consistency. Efficiency. Productivity. Best practices. These and more are the watchwords of the technical mindset.

Because of this power to combine techniques, it allows for organization at much greater scale than is possible with organic, grounded and cultural ways of organizing people. You break down all the various operations in a large undertaking into their own specialties. Each rationalized task is doing its part to make the larger enterprise possible. The person of the manager is the one adept as holding the various pieces together, making them operate smoothly and seamlessly. But even the manager is guided, controlled even, by a set of abstracted rationalized processes. He has a collection of best practices that he applies to the various situations encountered in his assigned areas of supervision. He makes nothing up on his own. He goes to training to learn the procedures developed by others and then applies them to his section. If he encounters problems or the policies don’t seem to be working the way they are supposed to, a meeting is called with other managers. They discuss the problems and make changes to the policies and procedures. These new updated policies are then applied. If the problem is serious, perhaps an expert is brought in for consultation. Or, the manager goes out for training. Usually, all problems are problems of system. If employees struggle, they need further training. The fault is usually that they are not fitting into the system. Perhaps the system is examined and adjusted. There is an emphasis on good process, even ahead of results. If good process is obtained, then it is assumed that good results will follow.

In the technical system, the vast majority of everything happens outside of one’s self. All problems are systemic. If something goes wrong, it is generally seen as unproductive to assign blame. Better if everyone gathers together and works towards fixing the systemic issues that created the problem. Once the system is sufficiently refined, all problems should disappear. The idea is that the system becomes completely frictionless, all problems having been eliminated.

All problems start to be seen through this lens. Every new problem is faced in the same way. Observe. Analyze. Break it down into its constituent parts. Render them into language. Lay the whole newly abstracted process out so that it can be discussed, problems discovered and fixed. Every problem becomes the material for further refinement and improvement of the system as a whole. As the system grows, more and more things are abstracted, rationalized and integrated into the whole. Every problem is approached this way, from the personal and interpersonal, to the running of major organizations, even the whole of society. It becomes such an ingrained part of who we are that this is how everything is understood and dealt with. There is only one solution, the technical.

This approach is tremendously powerful. The technical mindset built the modern world. From the founding of the United States, to the first factories, to military organization and logistics, to sales, to teaching, just about everything we do is rationalized and broken down. Every refuge of embedded knowledge is uncovered, examined, broken down, rationalized and systematized. Skills that were once closely held within guilds, giving the guilds tremendous power and material value, were gradually broken down, systematized and often mechanized. Soon they would be computerized. Then turned into You Tube videos and an app. As the power of computer systems, robotics and mechanization has grown, occupations and fields once thought safe from abstraction, rationalization and systematization are finding themselves subjected to incursion by sophisticated algorithms.

Even high level activities like “leadership” now fall under an ever larger collection of techniques, formulas and policies. Even when it seems like a leader is themselves leading by the force of their own ability, personality and character, often when you pop the hood, they too have taken on a surprising number of interconnected techniques into which they were trained. Whole organizations, entire fields, trundle along under the guidance of systems, policies, methodologies, structures and so forth which are largely person invariant. In other words, the people don’t really matter. They merely have to have enough baseline competence, often lower than you might think, and be willing to learn the methods and techniques as given. The advantage of such person invariant systems and organizations is that they can run with a relatively high floor of competency, the methods, structures and policies making up for a lot of personal deficiencies, producing consistent quality results. As long as you are attentive to training, follow through and monitoring, things can go quite well. The downside of raising the floor through good process in a well designed system is that it will also level out the highs. Because the emphasis is upon fitting into the system, true creativity that breaks the system is frowned upon. Society is not longer great, but settles into merely being average to above average.

As we have noted, there is this drive with technical thinking toward operating at ever larger scales. The idea is to reach economies of scale in every activity, usually towards the goal of accumulating ever more power and enhancing the ability to make ever more money. The use of system allows organizations to transcend the people within the organization as well as the restrictions of culture. If everything must be embedded within a culture, held in memory or in the collective consciousness of a group of people, it limits how large any enterprise can grow. Or it reduces the overall effectiveness of an organization as it grows. Once a way of doing something is abstracted and turned into a repeatable, rationalized and person invariant system, there is almost no limits to growth. This is the essential idea behind the franchise. You run a business. You analyze everything, break it down into a system and make it repeatable and teachable. You then can sell this idea to others. The power of it is undeniable. It is used in business, government, churches, charitable organizations and in almost every field and activity.

The downside is that the whole thing is very dehumanizing. It is also totalizing. When every problem is thought about in technical terms, what you end up with is actually a grand totalitarian technical system. It may not seem that way because you have interiorized technique in all you do and how you think about every problem. But if that is the case, is that not the definition of a totalitarian system? It does not merely demand your obedience, but demands that you think in the ways it wishes you to think. It is not the content of your own thoughts and abilities which matter, but rather your willingness to adapt yourself to technical thinking in all areas of life. All problems become technical problems. Even your family Christmas is a technical problem.

You too can have the perfect family Christmas if you are willing to implement the right plan and follow the system as laid out in the Christmas planning guide. The system dictates the way in which we think and increasingly the way we think leads to a single unified set of answers. We have all become NPCs. Non-Player Characters. This is why taking over the system as system is so unappealing. If you institute your own so-called “conservative” policies within this system using its institutions and mechanisms, the system will end up making you every bit an NPC as the NPCs you are replacing. It is the nature of the technical system.

Part of the problem we have in confronting the system is that we are so much enmeshed in its ways and patterns of thought that we no longer even see it anymore. The system sets the terms of the debate and we cannot imagine any other terms. Or they horrify us. Seemingly anodyne ideas like “The Rule of Law” or a “Rules Based Order” are second nature to us. Culturally, they are so much a part of us now that we struggle to imagine a world that is not “rules based.” We just assume that this is the way society must be. We expect there to be a universal policy manual for everything. There is a guidebook, a procedural manual, a set of techniques, a policy, a certification we can earn to address every situation we might face. We want to live within this thing that Carl Schmitt identified as a closed system of rationality. Every problem has been uncovered, broken down and now has a plan that can be referenced when needed. We cannot see how a society’s laws might function differently in a different context. We are told that to not have the universal policy manual is to have a society built on tyranny.

The technical system we know today was not implemented overnight. It began as an attempt to address very specific problems, mainly that of the unequal distribution of talent and quality of persons, in both ability and morals. System was also embraced in the quest to reduce inefficiencies, to create greater standardization, to produce more consistent outcomes, to increase productivity, to reduce costs, to reduce dependency on people, to break the power of associations, guilds, societies and the like, which maintained their power and economic value by closely guarding their knowledge. It had a political impact, in that by implementing systems, you could wrest power from powerful men, shifting it to the system. By restraining them within a system, even a loose system of checks and balances, it was thought you could reduce the tyranny of men as well their incompetency impacting the governance of society. It had an economic impact, in that all of society, in government and business, employing the emerging technical systems of the merchant class in both areas of life, harmonized them towards the efficient movement of capital. In this, they were wildly successful, producing levels of wealth and apparent freedoms unknown to mankind.

The price, though, was gradually subordinating all things under the influence of “the system” and its way of thinking, turning an ever greater number of us into NPCs, many more of us that we might think, and in many more situations than we might expect. We are, all of us, to some degree, subservient to the technical system and integrated dutifully into some form of Non-Player Character habits and mindset, more than we are aware. Many of us chafe against this. Many of us live with a sense of cognitive dissonance within the system, knowing that something is wrong but are unable to put our finger on it.

But what is the alternative? First of all, it is not a “system.” Feudalism, for example, was not a “system of governance.” Only someone who is on this side of modernity could look at it this way. We want to analyze it, break it down, identify its constituent parts and relations, abstract them and lay it out into a rational system. Feudalism was, at its heart, a set of loyalty relationships worked out over time, organically embedded within a culture, held mostly in memory and understood intuitively. What was written down in terms of “laws” should be seen as the visible part of an iceberg, the bulk of which remains below the water. It was a means of government worked out largely by men who could not read or write. By custom and tradition, something held mostly in collective memory, they governed an entire continent for about 800 years. Honor and obligation held it all together. It was not unified. It was not a cohesive whole.

Do we need to re-embrace a feudal system? No, not necessarily. Even if we wanted to do so, could we? I mention it just to draw the contrast. The defining characteristic of the technical, the managerial system, is that it involves “the plan.” The revolutionary period became what it was because the business skills of the merchant class were applied towards turning the grievances that led to the American and French Revolutions into a set of structures and institutions. They the turned the reasons for revolt into an rational plan that could be imposed upon society, remaking it, shaping it, instantiating those ideals into a set of constructs and institutions. The ideals of the revolt would be secured in the revolutionary structures established in its wake.

This emphasis on creating and implementing the revolutionary plan, intentionally shifted the attention away from persons to the structures. In the American context this means that one guards against tyranny and political ambition by pitting ambitious men off against each other in a balance of powers. You give some power to different people and then within a system of checks and balances, you design the system such that each of the other groups, guarding their own turf, will naturally restrain the ambitions of others, thus preventing tyranny from arising. The design of the system would overcome the flaws within men. None of these changes happened overnight, but in the lead up to the period of the American and French Revolutions, a shift was taking place which was concurrent with the rise of scientific and rational thinking, this notion that the problems we faced as human beings could be “solved.” They began applying themselves to solving problems everywhere where they found them. The same spirit which drove the rise of the merchant class in the first place also brought quite a number of successes in this regard. Everywhere plans were put in place to solve problems. Problems were analyzed, broken down, abstracted, and then solutions were implemented to solve them. This is the thing that marks the revolutionary era, this idea that the problems of society, of governance, of power, could all be solved by implementing the revolutionary plan.

"We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

This era marks a transition in how the problems of the governance of society would be approached. No longer would the prime emphasis be on the person; rather, the emphasis would be on improving the system. We need a better plan, a better system.

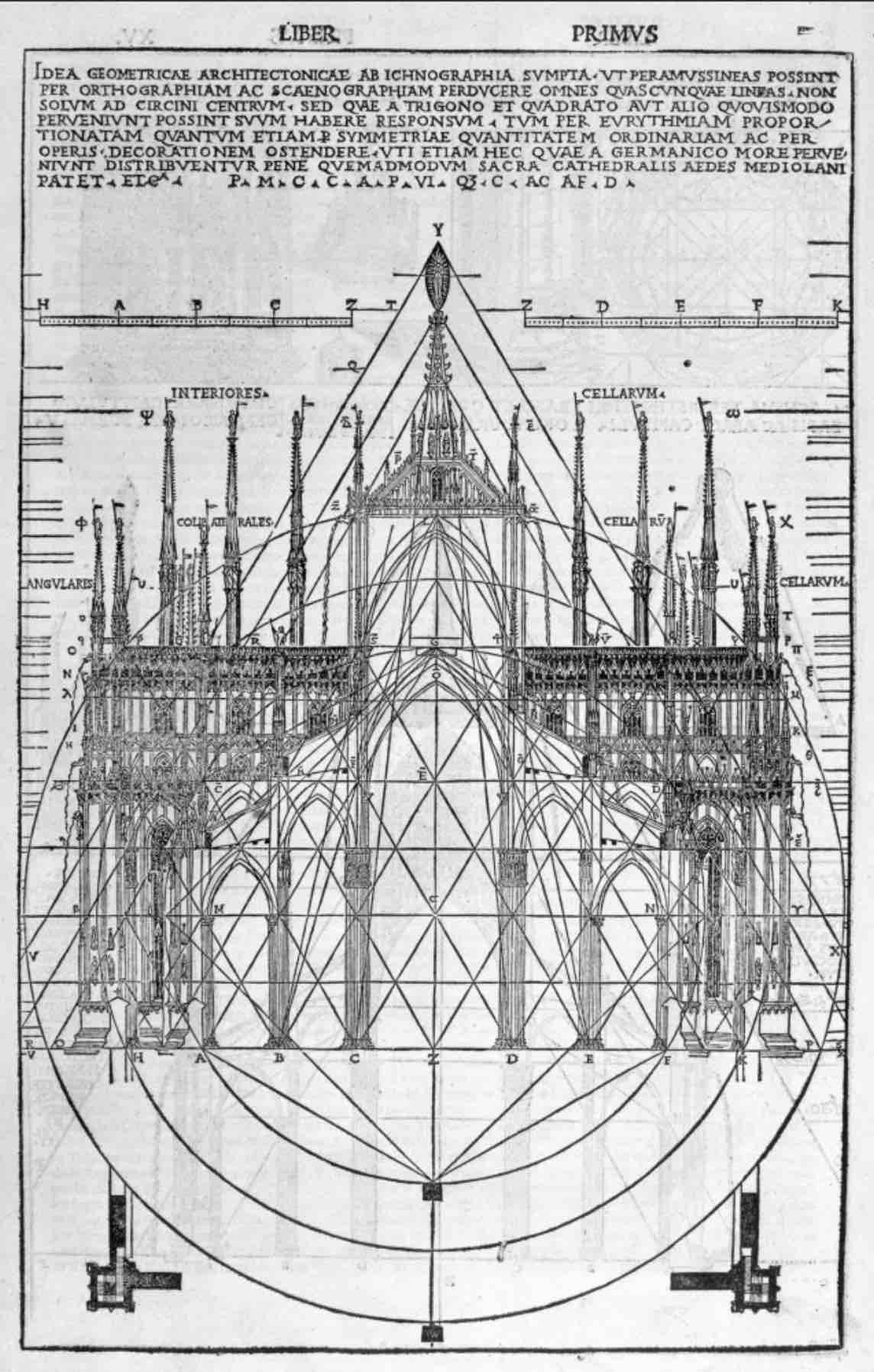

In this regard, as hard as it might be, we need to resist the urge to “have a plan.” How do you do this? How do you intentionally start a parallel community without having a plan? You can’t. I don’t think that it has ever been done. Even ancient communities show intentionality about their design and implementation. The problem is not intentionality. Nothing happens without it. The great Gothic cathedrals were built well before the era of rational planning, project management, CAD programs, or even the mathematics used by engineers today. Much of the knowledge employed by the masons had been learned and interiorized over numerous generations, held within the memories of families, guilds; passed on father to son, master to apprentice, generation after generation. To me this makes a lot of sense. If you work alongside capable tradesmen, many of them can build quite a lot without ever having to make or reference a plan, or even a set of drawings. They will when they have to, but it often a lot less necessary than one might think. The cathedral builders would make scale models to help with the visualization. But by the 1500’s a surprising degree of rationalization had already taken place, as evidenced by these drawings of the cathedral in Milan.

What is interesting is that even though they were applying mathematics and ratios to the design, the actual cathedral does differ from the plan, notably the main dome.

The picture I am trying to paint here is one in which the knowledge of how to do things, how to make things, how to run things, becomes intentionally re-embedded within the cultural life of the community. As discussed in a previous piece on parallel communities, we will not be able to avoid the use of technology. But intentionally changing our relationship with it should be part of this transformation.

We use technology, but we do so out of necessity, not as a progressive means of self-salvation. We build machines to last, machines that can be repaired and maintained, machines that incorporate aesthetic elements into their design, that are not alien but rather integrated into their environment. Machines are used to aid human skill and enhance it, but not replace it. Keeping people connected to the world in which they work is important. The idea is to enhance human agency. We strive for a different kind of efficiency, one which comes not through mechanization, but through the economy of motion that comes with mastery. It recognizes that the real value is with people. Enhancing and maximizing the capabilities of people, not systems, should be the goal.

The rules and customs which govern society should mostly be held in collective memory. They should be simple, few and flexible for a wide range of situations. They recognized that many of life’s decisions cannot be planned out in advance and must be made in the moment by wise men. And this really is the rub. Much of our current system is designed to guard and protect us against being ruled by men. It also shields us from having to take responsibility for failures. We are content to operate in the managerial middle. We assume that it is a high degree of average performance, and it has been. But this is changing. The managerial approach is gradually winnowing out from among us the kinds of qualities needed to create the systems that we now manage.

What the systems designers often neglect to see is that abstract rationalized systems, processes, machines and devices can never perfectly capture the full nature of the tasks. There is always some level of embedded, intuitive knowledge which remains. There are limits to mechanization. There are things that machines can’t do. Recently there have been stories surfacing that it might not be possible to go to the moon anymore because most of the engineers who built the rockets have passed on and with them has gone a lot of the undocumented knowledge on how to build moon rockets. It sounds crazy. But it is not as wild an idea as you might think. Eemonn Fingleton argued that there is a tremendous amount of embedded knowledge in every factory, even one that is highly mechanized.

There are tricks for getting the machines to run right and produce things just the right way. Every time you ship a plant overseas you lose a whole generation of organic knowledge that cannot be replaced. Re-patriating factories to North America would require re-learning all the embedded knowledge required to make manufacturing plants work well again. This reality is often lost on those who spend much of their lives dealing in abstractions, in rationalized plans and systems. It often appears that these operations, because they are mechanical and technical, are completely portable and fungible, but they are not.

The frightening thing for us in letting go and resisting the machines, the totalizing administrative system, is that we will have to learn to let go of the safety of the policies, systems, controls and rules which govern our society. It means letting go of a “rules based system” for a people and culture based system. It does not mean throwing out law or even the idea of law. Not at all. But it is a recognition that law cannot account for every situation, every possibility, every eventuality. We have to open ourselves up to the idea that people will be incompetent and/or corrupt and that the system cannot protect us from them. In truth, once they know how to work the system, it is the very system which is supposed to protect us from them, that becomes the shield for the corrupt and incompetent. To cultivate and access the potential for human greatness, though, means once again putting people directly in charge and then holding them accountable for their leadership and management.

Putting our reliance in actual leaders, letting them as people be in charge of things, letting them lead, does mean that we will not be able to manage our society at the same level of scale or efficiency, or with the same degree of consistency or homogeneity everywhere. A quote from Star Wars captures this: “How will the emperor maintain control without the bureaucracy?” Well, the answer is the same then as now, “The regional governors will have direct control over their territories.” This is meant literally. They will be put in charge and will run things as they see fit. They will be held accountable. In past times, that often meant paying the price with one’s life, title, the future of one’s family, or at the very least disgrace and disfavour. As we contemplate starting parallel communities or reforming the empire to make it less administrative, less totalizing, less inhuman, the solution is to re-humanize the processes of administration. That means letting capable people loose to “cook” as the kids say.

Won’t this lead to the dreaded “cult of personality?” Perhaps. But real leaders have charisma. They have some quality about them which makes other men follow them. The essence of leadership is the ability to command the loyalty of other men. Successful leaders are able to make decisions in the moment which benefit those who follow them. Managers, in contrast, merely have to preside over a system or structure for which many of the decisions have been made for them in the form of policy. They mostly enforce the rules, the order, that someone else designed for them. Many today confuse leadership with management. A leader is responsible for the choices they make. If they continue to make good choices and their followers benefit as a result, their command in leadership grows. The manager is responsible only for following, implementing, and enforcing an existing order, the artifact of choices made by others. They are tasked with ensuring “buy-in” into the policies, for ensuring proper compliance, for training people into some framework which was there before they got there and will exist after they leave. The managers themselves do not matter. There is much more room for incompetent managers than there is for incompetent leaders. The latter tend not to last long.

Leaders garner followers. They build personal networks of loyalty, benefit and privilege that becomes threatened in the absence of the leader. Succession is a problem. Tyranny is a problem. We live in a sinful world and there is no way to prevent this reality from being a problem. Laws cannot prevent it. System cannot prevent it. Even culture cannot prevent it. We are approaching a reality in which the contrast is growing ever more stark. Do we keep investing our trust in an increasingly oppressive, totalizing, corrupt, dehumanizing system, or are we willing to risk once again putting men in charge, doing the work of raising them in virtue, anchored within a tight-knit living culture? There are no guarantees. There is no perfect way of doing things.

But one of the goals of building parallel communities is about human flourishing. It is not about building a newer or better system. It is not about building a flourishing system. So, the goal, then, is to prioritize doing things that give people the chance to flourish, giving leaders the chance to lead by the force of their own character and ability. Giving them the chance to flourish also means giving them the chance to fail. But the risk we must take is to once again allow people, including strong leaders, to flourish. This means removing the shackles of the system that today binds them and hinders them from doing just that. What will restrain them? This is what faith, culture and tradition are for. Again, there are no guarantees that this will not end in tyranny or incompetence. But, if we wish to avoid the rise of tyrants and warlords, we may want to begin practicing new forms of both community and governance, ways that encourage the cultivation and flourishing of a new leadership class within a new ethos of nobility. This is perhaps one of the rewards which parallel communities can offer ambitious, talented men. The chance to really become a leader of men in a way that our current system is designed to prevent. Come, step outside the system. Cast a vision. Inspire other men to follow. Then build, and flourish. Help others to succeed when they follow. Become a leader. Become part of a new nobility.

Great article, Kruptos. Even in business where system and process has achieved incredible feats (think lean manufacturing of Toyota Production System), the inevitable long-term mediocrity (competency crisis) is what enables leader and skill centric startups to so easily disrupt an industry. Huge potential for anybody who stops regarding labor as a commodity and synthesizes guild-like journeymen as employee owners with the best that system and process affords e.g. quality.

In my opinion, a good source of memorable rules and customs is the Bible.