Mastery: The Path to Creativity

I came across a tweet from John Vervaeke on the need to disrupt your normal patterns of thought lest you become locked into a particular way of thinking. I disagree.

There is a lot of energy expended these days to promote this things called “creativity.” From a very young age children are encouraged to be expressive. Being free from the constraints of others so that you can give outlet to your inner vision without hesitation or fear is seen as the height of authenticity. We are encouraged to break down the barriers that constrain us and keep us hemmed in. Free thinking is the goal. A recent tweet from John Vervaeke came across my feed, typical of this kind of thinking for adults:

He is correct that your brain is incredible at pattern recognition. This is a feature, though, not a bug. Vervaeke speaks about the “problem” of getting “trapped” in a particular way of thinking. I put these words in quotes because these are not necessarily bad things. In fact, they are a good thing. They are the foundation for something called “mastery.” I would agree with John that in certain contexts and situations getting locked into a particular way of thinking can become a bad, even dangerous and destructive thing. But those situations only arise because you have become really good at something and it works for you, until it doesn’t, and you need to adapt to new circumstances but can’t. But until those circumstances are thrust upon you, there is far more benefit in recognizing patterns and developing deeply ingrained knowledge, skills and abilities.

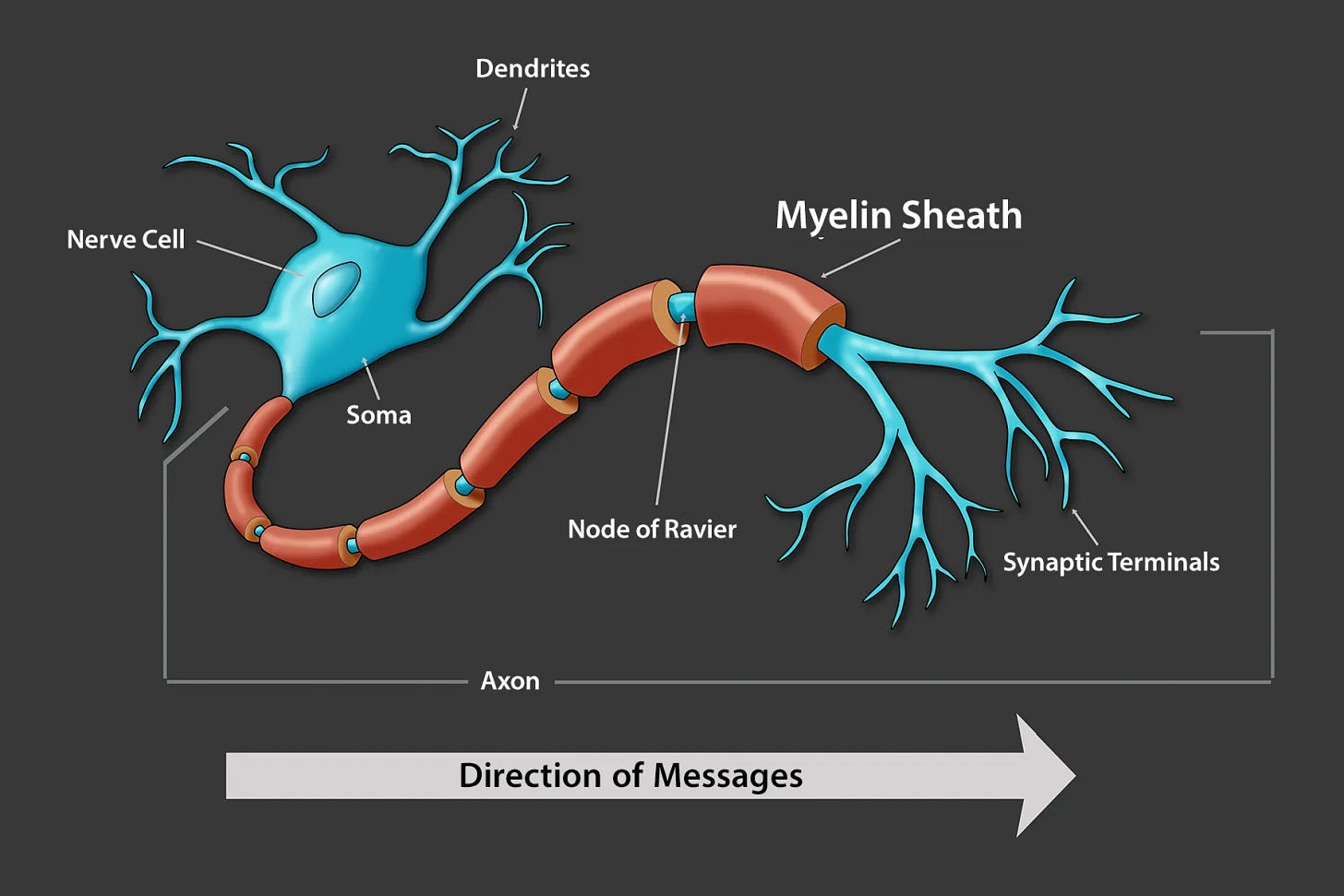

Once you understand some more about how our brains work, the physiology of “mind,” this idea that we have to be “pattern disrupters,” from all that I have learned, becomes suspect. When we are born, our brains are not yet fully developed. The structure of our brain at a cellular level actually grows and develops in response to our learning. We build brain structure around language, skills, habits, memories. The brain is not like a computer chip or a hard drive. As you learn and repeat things, both good and bad, our brain architecture becomes more efficient at doing those things. This is why you practice your golf swing until it becomes second nature and you don’t have to think about it. For anyone who has tried to golf while thinking about doing every aspect of the swing correctly, it doesn’t go well. This goes for all kinds of activities from things like language, to fine motor skills, to athletic abilities, to intellectual pursuits. As you do them, you build your brain around those activities so that they demand less conscious thought. At the cellular level, you build not only the nerve architecture, but also a thing called myelin sheathes around the nerves that aid in speeding up and making nerve activity more efficient.

The more that you practice things, the more that your brain structure gets built around doing these things, the faster, easier and more natural, second nature they become.

Imagine a world where every time you encountered something, or were required to do a task, that you had no memory, no collection of patterns, no structure built up to provide a foundation for you through which to understand the world or act within it. Complete openness would meaning understanding nothing and being able to do nothing. You would be paralyzed by constantly have to relearn everything all the time. Every skill would be new to you all the time. The world would flow over you in a disordered and chaotic flow of sensations. To make sense of the world you have to see patterns, filter out some inputs in favour of others. You have to be able to see and recognize threats and dangers. You need pattern recognition to able to protect yourself, feed yourself, sustain yourself bodily, socially, mentally, intellectually, and emotionally. Patterns are vital and necessary. And you have to have a developed enough brain that these patterns are recognized instantly, often pre-consciously. You step back from an oncoming car instinctually. Your hand pulls back from a hot stove element instinctually. You don’t even think about it. But all of this has to be learned and your brain has to build around this knowledge and it needs to be efficient and quick in the recognition of these patterns. Your life often depends upon it.

Your brain builds itself around these patterns, increasing nerve density and the thickness of the myelin sheathe. It is this development of the myelin sheathe that makes our thinking and habits more efficient. Because of this architecture, because you are not expending energy on basic pattern recognition or the basics of a skill, it allows you your brain, and your mind with it, to focus on higher order aspects of the activity. It can even allow you to be doing one thing while thinking of something else.

The downside of this is that these myelin sheathes, once grown by our brain, don’t ungrow. Their deterioration is what causes a number of neurological diseases. What this means is that change is hard, especially when it comes to bad habits. You have literally built your brain around the activity and the reward structure that this harmful activity generates. As you give yourself over to bad habits and practice them, you actually make the doing of them more efficient and natural for your brain such that not doing them seems unnatural. Your sins and bad habits, if you practice them enough, become you on easy mode. They take no effort because you have practiced them so much and made them a part of you. The doing of them becomes pre-conscious. This is why you can find yourself picking up your phone and scrolling mindlessly without purpose. You have so trained yourself to do this such that you have wired your brain to just instinctively pick up the phone and scroll. People who say that you are not your sins have no idea what they are talking about. You are your sins because you have built your mind around them. This is who you are. You have practiced them and made them a part of you, even if they are just habits of mind like lust, greed, anger, envy, jealously, pride or so forth. You are your sins, even if they are “merely” of the mind.

When you attempt change, the current structure of your brain doesn’t just disappear. In fact, the myelin sheath structure remains. What you have to do is very intentionally re-write your brain by practicing something new that then builds a new structure over the old one. It takes real effort and focus, but it can be done. But the old, baring a miracle, will remain. This is why a smoker can suddenly feel an intense desire to smoke even a decade or more after quitting. Something triggered that old network that still lays there buried beneath the new overlying structure of non-smoking habits and it all comes back hard, largely because you are not ready for it. And because, as you get older, your body produces less myelin over time, developing new habits as you age becomes harder and harder. This is why training up a child in the way that is right is so important. It really does stay with them because their brains are built around all of the positive things you have invested into them. This is also why in churches you cannot leave discipleship to happenstance, especially after a conversion. This is when it is crucial to actively engage and cultivate the habits of faith in a convert. Its why, even within a proper understanding of covenant, we need to disciple our children. It also speaks to things like immigration from foreign cultures. They need a powerful set of incentives, from a dominant, even domineering new cultural context, or they need to be taken actively in hand and taught how to be part of this new society.

To reiterate, in order to get good at something, at anything, regardless of how much innate ability you might have, you must practice and build the muscle memory and brain structure around this activity. To get good at something you must develop deep patterns in your body at the cellular level around these skills and abilities. If you are constantly having to adapt to new situations constantly, it makes it very hard to get good at any one thing because you cannot develop the deep patterns necessary.

As thinker and author Iain McGilchrist has observed, even having this developmental understanding of brain structure at a cellular level, we need to recognize that we have two sides of our brain that, broadly speaking, specialize in performing different activities. One half of our brain is good at perceiving the world as it, grasping it intuitively and instinctually. The other side of the brain is good at taking what first has grasped intuitively, organizing it, turning it into patterns and schema, naming them and putting them into a form like language to enable them to be communicated easily and efficiently. In the modern era, more has been demanded of us from the ordering and efficiency side of our brain. The technical world deals with things in a technological way. The more we press this side of ourselves, argues McGilchrist, the more that we develop something like a kind of social autism. The technological world demands of us that we emphasize ordering the world and engaging with it efficiently to the detriment of our ability to perceive the world intuitively. Ideally, the two are meant to be held in balance, but the machine-like quality of the modern world enframes us and interrupts the balance between perception and ordered efficiency.

In a healthy way, when you learn a skill, like playing the piano, or woodworking, or caring for farm animals or even reading philosophy or the scriptures, as you build the structures of your brain around this task, both in perception and in ordered sense making, you reach a point where you have to spend less energy on them, opening up new possibilities. Music will come to you as you play the piano. You will develop a feel for the wood, seeing in the wood what it will become in your hands. As you interiorize texts like those of scripture, or philosophy, or literature, as the words ingrain themselves in you, as your brain builds around them, now that you have to spend less energy on the text itself, your mind becomes free to intuit the deeper meanings and connections that emerge. Mastery of the material, of the discipline, of the art, of the craft, allows creativity to emerge, often unbidden, from this ordered structure of the brain and the mind. You really do have to do the work and put in the hours to gain this kind of mastery, if it comes at all.

Even with intuition, grasping the world and the patterns that are there within it, requires practice. This is doubly true for grasping the metaphysical and the supernatural. There are no short cuts in “going up the mountain” to meet God. One must put in the time, practice, learning to sift through the various perceptions to see and to sense God at work. We often talk about us having faith in God. But can God have faith in you? The disciplines of prayer and the reading of scripture show a reliability, a stick-to-it-ness. The spiritual aspect of our being is like any other. You run to get in shape. You practice the piano to get good at it. In the same way, if you want to perceive God’s presence and his gracious desire to be near to you, putting in the work to develop the habits of brain, mind and spirit, allow the pathways to be developed as a cellular level for you to embrace benefits of grace. Because wisdom is about seeing with the eyes of God into the complexities of life that confront us, it demands a development of the ability to perceive, to see. This is also why I think it is that wisdom comes with age. It takes time to develop that part of ourselves that grasps the world intuitively, metaphysically, spiritually, and mystically.

That said, there are certain disciplines, especially in the maths and sciences where brain plasticity matters more than deeply ingrained patterns of thought, where working with the subject matter over a long time actually makes you less creative and innovative. Perhaps it is the technical nature of the disciplines that closes off innovation over time. But it is something that Thomas Khun observed. New scientific paradigms are often championed by the young. They have an idea, then they spend the rest of their life trying to demonstrate and prove that they are right. But even here, you must reach a certain base level of knowledge, a base level that is quite high actually. You need to practice, put in the time, get yourself to a very high level of expertise, and do so while still at an age where your brain is still maturing and your mind has not settled into its more mature patterns, such that it is possible to make rapids jumps and shifts. What is interesting is that the older scientific thinkers generally need change forced upon them from outside, the “young Turks” forcing a paradigm shift. In this regard, science resists the influence of wisdom in favour of cleverness. And the scientific and technological society thus resists the presence and the emergence of wisdom in favour of the new and innovative. It is world where the clever fools come to dominate.

In the older world of learned skills, before the emergence of the technological society, people benefited from the stability of this world. Once you learned a skill, you could count on it having usefulness throughout your life. It allowed you to build on these skills, refine them, master them, add to them. As you did so, as you expended less energy on the skills, it allowed creativity to emerge from mastery. It also allowed wisdom to emerge. Culture is the same. As a society interiorizes certain habits and skills, certain ways of life, these can become ingrained into the community, it can open tremendous energy to interact with the world intuitively out of the shared social architecture. What happens within our brains, happens within a cohesive society such that it expends less energy on doing all the small things, opening up a kind of collective social resource where, because they are not having to expend social energy to maintain and navigate all of these social structures, it opens the possibility for creativity to emerge from this situation of social mastery. This is why “diversity is our strength” is such a lie. If you are expending a lot of social energy navigating all of the differences between people, your society is like trying to golf while making changes to your golf swing.

The modern west was really built by emphasizing and pressing the “young Turk” mentality of breaking down existing orthodoxies so as to press innovation and change upon us. The cost of this over time is that socially and individually we become less able to grasp the world intuitively. Everything is about refining theories, challenging theories, about improving processes and developing new and better techniques. Yes, as Vervaeke notes, this requires a certain plasticity of mind. But as we emphasize this scientific side of ourselves where the drive is to always be breaking down orthodoxies, refining processes and making them more efficient is that the cost of this is that socially and individually we are less able to grasp the world directly, intuitively. We are enframed within a world that has been optimized for one half of our brain. Everything is more efficient, more powerful, but at the cost of making us less and less able to directly grasp the world intuitively. Everything is about “creative destruction.” The old ways must be broken down to make way for new innovations.

But all these clever new discoveries, innovations and optimizations are not being fed from our intuitive grasp of the world as it is, the world as opened up to us by the deep mastery of a skill, including the world of the metaphysical and the supernatural. Rather, we are becoming more and more like LLM algorithm that is being recursively fed back the results of its own data. We as people are slowly breaking down because, enframed by our own technical and scientific proficiency, choosing cleverness over wisdom, we can no longer intuit the world properly.

The one phrase that caught me in Vervaeke’s post was his suggestion of introducing techniques that can disrupt fixations in pattern recognition. The problems is that techniques are themselves already a form of abstracted and rationalized pattern recognition. What Vervaeke is suggesting, whether unintentionally or not, is that we technologize the process of feeding technologized inputs back into our psyches with the intent of opening up our intuition. To me, this seems more like the recursive training of an LLM algorithm than anything resembling real intuition.

Real intuition comes through mastery. Mastery of deeply learned skills. One of those skills is that of perception. Learning to pay attention to the world intuitively, directly. But in many cases, our connection with the world emerges out of mastery. We come to feel and intuit the music because we have mastered an instrument. Or, we have mastered the art of listening to the music. We come to feel the wood because we have mastered the craft of woodworking. We come to read the forest because we have mastered the art of tracking. We come to read the winds because we have mastered the art of sailing. We come to hear the voice of God because we have mastered the scriptures and the art of prayer. Yes, we are seeing the world from within a deeply ingrained structure. But it is this very structure that frees our mind to see. But unless you are baby who is seeing everything for the first time, you are always seeing from within a structure. And even the baby is not a blank slate, for he has an inborn structure that makes him human. And narrowed down from his humanity, he carries within himself the genetic patterning of his parents and is born into a world where they, and the family and the community create a further structure for him to encounter the world. Within this context the child is raised up, hopefully into the full mastery of his faculties, both individually and culturally.

Our current society, the technological society, is built on this idea of creative destruction, arguing that you need to constantly introduce outside shocks to break down existing orthodoxies so that innovation might occur. In this sense, the modern scientific and technological society is a kind of anti-culture. It has been very successful, but the cost has been that it has slowly cut us off from true intuition, the kind of intuition that can only emerge from the cultivation of mastery that then frees us to see the from within the structures of mastery. We can no longer properly intuit the world directly. We lose the true wisdom that comes from the interplay of long ingrained patterns of seeing which are constantly being layered with new intuitions that come from the dialectic patterns of knowing and an intuitive grasp of the world as it is. And this is why problems continue to mount that we have no idea how to solve because as clever as we are, we lack the necessary wisdom. And so we continue to lean into what got us here manically and autistically looking to the clever to smash orthodoxies so as to impose yet another round of paradigm shifts and new techniques. We never arrive at the point where wisdom emerges, the wisdom that might allow us to truly “see” in a way that our scientific and technological society cannot.

An essential explication of the world in which most of us flounder around. A personal building block in understanding our path from the Enlightenment. One of the others? This writer’s essay entitled something like “Boys Don’t Learn Latin Anymore”.