Man or Machine? The "Necessary" Total Revolution: Part 6 of a Deep Dive into Jacques Ellul's "Autopsy of Revolution"

"The state" will remain the enemy of the people until it is brought down. The only way to bring down the state is to bring about the end of the modern world. Is the cost too high?

So here we are. Ellul has explained it all to us. We have, since the great revolutions of the eighteenth century, been building a grand abstract, rational system that we now know as “the administrative state.” Jacques Ellul is often criticized for being long on description, but short on prescription. He identifies the problem, but does not tell us what to do about it. “Autopsy of Revolution” is different in that regard. Here is gives not just the diagnosis, but also the cure, if we have the stomach for it.

In talking about revolution at this point in the work, he draws on a concept he has used elsewhere in other writings, that of “necessity.” Ellul is cognizant that we live in a world of sin and evil, where people are born flawed and corrupt and they do bad things. The long term result of living in this world is that many of the choices we face are not strictly between good and evil but between the greater evil and the lesser evil. Ellul employs this category so as to avoid justifying moral evils as something good. He identifies his position as “Christian realism.” Sometimes the right choice is to do something evil, something that imperils your soul, because the other alternative is worse. You must stare directly at the fullness of what you have done, acknowledge it, and lean of the grace of God. With that in mind, Ellul says this as the final chapter of this work begins:

“For us ‘necessary’ denotes a moral imperative, a revolution that must be made.” Emphasis is Ellul’s

Ellul is staring at the choices we face as human beings in relation to the state apparatus we have built as part of the larger technological society and declares that we face a “necessary” choice. Some might push back and argue that “human progress” is rendering the need for revolution unnecessary. Society will work through its current tensions as step-by-step we slowly perfect all its mechanisms. But present day conditions seem to speak to a different reality, that progress has stalled. We are in decline. All of our day-to-day experiences breed the feelings that lead to revolution.

But Ellul wants us to check our revulsion and indignation. These types of emotions weaken us and make us vulnerable to manipulation by propaganda. If we act, it should be a calm clear choice, freely made. We live in a society which is every more abstract, less grounded in material reality. Significant numbers of us make our living as part of the laptop or email class. We spend our days dealing with abstractions, disconnected from the demands and needs of material reality. We are immersed in dancing images, with us all the time through the devices in out pockets. As a result, the problems we face and the threats to our existence, our future, are also ever more abstract, mysterious. We try to focus on problems, causes and sources for our dilemmas, yet the phenomena we encounter often turn out to be mere appearances. How do you fight an abstract reality mediated to us in flickering images that dance across our computer screens? When you can’t even properly see and experience the problem, or identify why you feel the way you do, or how you got into your current situation, how do you know when you have reached conditions for a “necessary” revolution?

“For revolution to be necessary, two conditions are requisite: first, man must sense to some degree that he cannot endure life as it is, even though he may not be able to explain why; secondly, the basic social structures must be blocked, that is, incapable of acting to satisfy his needs or providing access to that satisfaction.”

Ellul argues that if there is any possibility of settling a conflict without revolution, even if it is a revolt, man will find it and the revolution will not happen. The point of the necessary revolution is to force the exception which will by necessity result in the remaking of the entire system, giving it a new foundation. This is not tinkering. This is the “big one” for which the current system cannot adapt. If the exception cannot be embraced and society cannot find a new foundation, complete social collapse would be the other alternative. Ellul argues that the second essential condition simply does not exist at this time.

For those of us who are paying attention, the current reality speaks to a growing totalitarianism and the trend lines for the future do seem ominous; but at the same time, there is still a lot of slack and excess in the system. Things do not feel “blocked.” If they are blocked for some, it has not reached a critical mass of people. The world is not what it once was, especially for those like myself who grew up in the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s. At the same time, sensing that the trend lines are not good, is not the same thing as living within an intolerable situation with no other avenue but revolution. There are still other forks in the road which can be taken.

That said, while you can still go to Disneyland or vacation in Europe, while you can still buy that brand new truck, or walk about in relative freedom, there are growing anxieties about our lives. They don’t feel like they flourish they way we expect that they should. There is something about the system that seems off. It is grand and globe spanning. But the things which are supposed to give us meaning—that trip to Europe, the new truck, the current entertainments, the latest purchase, the media we consume—seem somehow insignificant. They don’t provide the meaning we crave. The rates of SSRI usage seems to speak to this. We sense that a meaningful life is not open to us. We attempted to replace the sacred, the presence of God, the role of religion, the life of the community with the acquisition of material goods. As our prosperity grew, so too did our anxiety. We had material bounty, but not much else. Now that this prosperity seems increasingly threatened, where do we turn to ease our anxieties?

“The vast adventure that has absorbed us for the past two centuries has left each of us in his own fashion more frustrated than triumphant, whether because we admit the futility of our occupations, or because the paltry quality of our satisfactions and our leisure, or the questionable values and way of life we pursue.”

Our lives are empty, but we refuse to admit this, lest it calls into question and invalidates everything we have pursued and built as a society. Our goals and aspirations all somehow seem misguided and futile. The world we thought we were building as a society has not arrived. Increasingly, it seems as if we waste our lives working in “bullshit jobs.” We lack the sacred standard that gives meaning to our existence. We have replaced the pursuit of God and the significance which a full spiritual life provided to chase historical significance. We were going to right all the wrongs and engineer the great society. And in spite of all the propaganda, the evidence of the failure of this titanic enterprise is everywhere all around us.

A significant part of the problem is that we have shattered communal life, telling ourselves that the individual is the foundational building block of society. But as each pursues his own satisfactions and his own beliefs, we have lost a sense of common purpose. The individual imagination is not enough. There must be a communicable reality which transcends the individual man. It must be at once grand and metaphysical, yet instantiated in the world around him, in the things he can see, touch, taste and the people he meets every day. This reality must be the product of a common shared sense of reality, true “common sense.” The individual cannot provide himself with a stable and satisfying purpose. The individual cannot manufacture for himself meaning in life out of whole cloth. Our society, if you can call it that, is banging its head against the reality that people living as individuals cannot give a society meaning.

“Yet the crucial question is life [and its meaning and purpose], and because industrial output does not overcome or remove or confront it, we say therefore that capitalist affluence has failed.”

This is the hard truth. We have excelled with our technical achievements. We have produced untold wealth and prosperity. But these same have not given our life meaning or purpose, nor have they satisfied our deepest spiritual yearnings. We are a hollowed out, empty people.

Ellul then zeros in one one idea, the linchpin of the whole system: growth.

“Everything is predicated on an ideology of growth, idealizing it and mistaking it for [human] progress.”

This idea, the we must have continual growth in profits, in income, in the size of our businesses, in material progress, in learning, in population, in everything shapes the whole of our experience and frames our aspirations as well as our interpretations of reality as a whole.

“…alterations conceived of as growth or even development ultimately reinforce a society’s self-image, never challenging it and inducing further conformity because that society clings to the self-image it projects, including its illusions of structural change, which always follows a pattern of exclusive quantitative growth.”

This idea of growth pushes us to want to produce more, make more, consume more. We must know more, invent more, build more. At the same time, society must grow ever more just, ever more equitable, ever more free. We consume ever more resources, never saying, “no” because we cannot stop growth in either production or consumption. It is not enough to make a steady, stable profit year after year, we need to grow our profits every year. The business must grow. The market must grow and expand. Every problem has a “growth” solution. If we grow technically and introduce “green” innovations, we can solve the problem of diminishing fossil fuel supplies. Our society must constantly be breaking down moral barriers so as to grow in compassion and freedom. Our rights must grow in number. It even defines our spiritual and moral lives. We are continually urged to “grow” as people. Personal growth, spiritual growth. Our churches are infected with the idea. We have confused the idea of discipleship and bearing witness with the growth of our church institutions. It is whole “church growth” movement. Everywhere we look things must grow, grow, grow. The growth idea drives and pushes “history” forward. There is the common refrain, that if you are not going forward, you are going backwards. The businessman and the political progressive share the same drives, expressed in different manners. It is an old impulse, that of Babel. We must build the tower ever higher, until it reaches the heavens. It is dangerous idea, argues Ellul. It causes us to believe that because we know more, produce more, control more, buy more, that we are more as a people. In fact the evidence is all around that we are the opposite. We have emptied ourselves and have become less as a people. Our drive for growth has made us less human, not more. It is this growth idea that that must be shattered, he argues. Only an “exception” level crisis, he says, can shatter this kind of core cultural drive.

“As I see it, that is precisely why revolution is indispensable and necessary: we must get off the standard one way street that starts with growth. That is a necessity.”

For Ellul, the question is not a matter of whether or not there should be a “necessary” revolution; rather, it is a matter of what kind. He boils it down to a binary, an either/or:

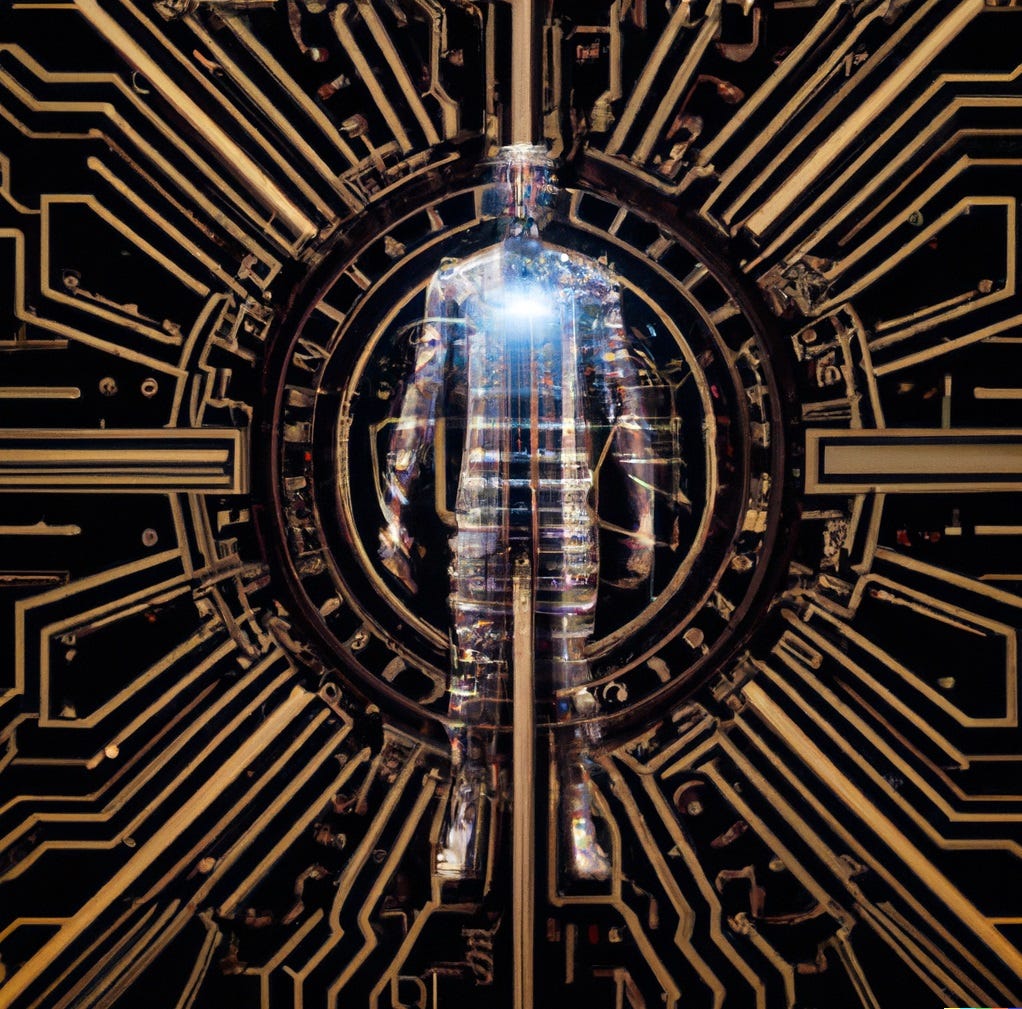

“A choice is forced upon us. We must decide between the accumulation, perfection and primacy of material things, and that doubt ridden and uncelebrated creature known as man.”

Must man be forced to adapt himself forever to the exigencies of the machine? Must he be shaped by the vast integrated technical system predicated on idea of growth? Must man subordinate himself to the demands of the internet of things? The two are irreconcilable, asserts Ellul. What will triumph? The needs of man or the demands of the machine?

“Yet the seemingly illogical choice I make is with man and all his imperfections. I reject out of hand the notion of human backwardness measured against the brilliant achievements of science to which man ought to adapt.”

This, he says, is a revolutionary attitude. At this point it might be fair to say that we are about see emerge the young Marxist Ellul, before his Christian conversion. He sees a blind act of faith, a stark decision that must be made.

“On the one side stands everything that technology is preparing and unquestionably will achieve, and we can project to some extent; on the other hand stands man with all his inadequacies, his dilemmas, and his unpredictability. This is the choice we must make, knowing no conciliation is possible. That is the essence of the revolutionary decision. It can have no other content in our times.”

Mankind vs. the technical system. The state in all its forms is the nexus through which it expands to encompass all things, enframing us as human beings within itself. Ellul argues that it has passed the point where we can master and control it. It has taken on a life of its own and its demands shape much of the entirety of our lives. It demands that we must push forward. We must grow. We must improve. We must develop. We must expand. We must assert control. Against this vast system, Ellul asserts that man, at his core is a revolutionary being.

“Revolution is man himself. I believe that man comes into being through his revolutionary acts. By radically challenging the totality of his environment down to its structures and values, he enters upon a new existence and changes in the process of changing his environment. Today that environment is technological.”

As I read that quote, it seems to me that faced with the totality of the technical monstrosity we have built and within which we have trapped ourselves, and wonder if Ellul has somehow forgotten his Christian faith and not been able to escape the pull of radical revolutionary thinking. There is a strong sense of “return” here. That it is time to hit the reset button. We must engage in a revolution against the revolution. We must take the blind leap of faith. Reason cannot see beyond this choice.

“He engages in revolution by a decision, a wager, an absurd gesture of revolt and rejection in the face of his human condition. His choice is absurd because its chances of success are minimal. But only through his decision to try to find some meaning in meaninglessness, to give meaning to an absurd act involving him completely, does man exist.”

Does Ellul see the act of faith as a kind of revolutionary act of self re-formation? Does he see the Christian struggle as the battle against “history” that is, the idea of historical progress, historical growth? It certainly seems that way.

“We are all bound to a community; but we can refuse to put up with it. And here is the necessity of which I speak: we must will, not this destiny, but the struggle against it…must revolution take the direction of history?”

What Ellul is calling for is the rejection of the idea of “growth” that is foundational to the idea of “human progress” which is foundational to the idea of “history.” His is a call to say “no” to history, progress and growth. We must ask what is good for man? Freedom is the rejection of history, the rejection of progress, the rejection of growth. He definitely casts this into the language of an act of faith:

“Revolutionaries are sorcerers. They strike the barren rock and water gushes forth.”

Here he evokes Moses in the desert, but recasts in terms acceptable to a materialist world. We are magicians calling on the forces of the universe; rather than men who trust in the command and power of God. There is a deep lesson in the story of Moses. In Numbers 20, Moses was commanded to speak to the rock and God would provide water for the people. Instead he struck it. Water came forth. But because he did not follow the explicit command of God, Moses was prevented from entering the promised Land. There is a lesson here. God may command us to strike the rock. Or he may command us to speak to it. Our primary act of faith, the leap we must take, is not first of all the revolutionary act, but rather that of trusting and obeying the command of God.

Ellul continues, drawing us back to earlier portions of the book, to the heart of the revolutionary act: the rejection of history:

“Revolution is necessarily an act of negation, a cleavage: it is an ‘anti.’”

He at least has the courage to be honest with the reader. Yes, this is utopian thinking. The current order must be swept away so something new can emerge. Utopian thinking is, he argues, counter-revolutionary. Our world is the product of “the revolution” having been instantiated. The only proper response to the revolutionary world is that of the counter-revolution. The negation of history. The nihilistic revolt that does not attempt to build anything.

“Revolution cannot be made in the name of values for the purpose of replacing one socio-economic-political system with a more efficient and nearly perfect one. It can only operate “counter.”

And:

“It is a necessity, I believe, for revolution to be negative and destructive. Its role is to challenge, and only as it begins to focus its defiance and rejection can it shape itself and assume value.”

What he is saying here is that we cannot when entering into the process of revolt against the current system have a plan. What will emerge as the new future can only come forth in the process of rejection. Again, this is self-conscious utopian thinking. Ellul seems to be grasping at this as a contrast to the plans of the managerially minded bourgeoisie whose organizational abilities realized the first revolution and built the system we have today. To plan is to be managerial. If we are managerial we are not really changing anything. To be against the managerial bourgeoisie is to reject the very idea of “the plan.” He argues that to oppose the current regime, your endeavor must be utopian in the sense that we must trust that the better, more human future will emerge on its own once the current inhuman system is swept away.

We must understand that the current managerial system cannot be brought down piecemeal. You cannot bring down the “bad” parts and keep the “good” parts. The good and the bad come together in the system. You can’t have the good without the bad. This is the nature of technique. It is not neutral. Rather, every technique, every system, every rational abstract plan, comes with both good and bad baked into the very systems themselves. As Ellul explains elsewhere, in The Technological Bluff:

First, all technical progress has its price.

Second, at each stage it raises more and greater problems than it solves.

Third, its harmful effects are inseparable from its beneficial effects.

Four, it has a great number of unforeseen effects.

The moment that the bourgeoisie managers instantiated the revolution in and through the rationalized system of government they developed, some form of the current managerial state was inevitable. Once the revolutionary plan was made real in the founding documents, as Ellul argued earlier in the book, the end result was always going to be that it would encompass and enfold all of life into itself.

“The globality is not artificial, forced, or haphazard; it is a systematic development that gradually has absorbed all the social components.”

The technical nature of society today means that all things are integrated into all other things. There is no divide between government or the private sector. There is no divide between countries. It is one global integrated system.

“The nature of the global society is such that no single element of it may be touched, or impaired or questioned without involving the whole.”

Ellul was saying this in 1969, before just-in-time global logistics and the internet. Once the system is challenged, it must be challenged everywhere. And once it is meaningfully challenged in one area, it will challenge the whole.

“Ours is the first society in which the whole is implied in each part. There can be no partial revolution. … The existence of a global society rules out any prospect of a sectorial revolution.”

I think Ellul is essentially correct here. If you wish to bring down the regime, and this means, as he has argued earlier, that the administrative state in all its forms and aspects is the enemy of the people, then this means bringing down the whole system. All of modernity and with it the whole of our modern life. Every convenience. Every comfort. Its prosperity. All of it. Why? Because if you attack part of it, and some part of the system survives, you will only make it stronger. This is a point Ellul made in The Political Illusion. The administrative state cannot be reformed and it cannot be bent for conservative purposes. It is at its heart revolutionary in its intent, that is, what we would call left-wing in its orientation. This is the nature of the technical system as a whole. Liberalism, technology and capitalism are all part of a whole cloth, one single entity. To break the power of the left you have to be willing to bring all of modernity down with it.

“In fact, any sectorial or tactically divided revolution will be reabsorbed and integrated into the corporate whole, which is fortified by the vigor and the new blood.”

As if anticipating our current moment:

“There is no cultural revolution, only total revolution.”

The culture war, if fought in such a way so as not to strengthen the system over time, must be a war against the whole global system of modernity. There is a reason “pride” flags fly in central Europe, Africa and Asia.

“Revolution, therefore, cannot restrict its attack to economic or political structures, for it is at the vital center of the assimilative system, the converging point of mechanism integrating the individual within the social system.”

You cannot bring down all the evils of the global economic and political system without also attacking technology and technical thinking at the same time, for it is technique which integrates us into the global political and economic system. It is the myriad of rationalized technical processes and systems so necessary, not just for instantiating the revolution, but, also for managing the global system itself, which insert themselves between us and reality, between man and the world such that our entire experience of everything is mediated through technology and technique. To once again connect with reality itself, we must strip away the curtain of the technical system.

“With a mediated and totally abstract system, no person or persons can be held responsible, no single organism can be blamed. Revolution, therefore, consists in attacking all instruments of mediation which alienate human beings from one another and from society.”

Ellul argues that world system we live in is very rigid and fragile. This fragility is masked by the illusion of constant surface changes. But beneath the buzzing surface, the underlying logic of the abstract rationalized technical system remains largely unchanged. At the heart of everything is the technological mindset which approaches every problem as a technical problem. The problem must be analyzed, broken down, its component parts abstracted and then turned into a plan, a system, a set of policies which can be applied to “fix” the problem. Every problem is approached in roughly the same way. This approach only has one direction. Greater complexity, integration and technical control over all things.

“Nowhere has the state become less of a state, less powerful or less managerial. Technology never regresses: it is increasingly the axis of our society.”

What was true in 1969 has only become more true today.

“Technology never retreats and is never challenged. … Our society is basically technological and statist; all characteristics point to that, and therefore if a necessary revolution be brought about, it will have to be founded on the realities of technology and the state.”

“The state” is the totality of the technical managerial system. It encompasses everything and integrates everything into itself, including the members of society who find their propose, their very being, expressed through the state writ large. The integration of all things into “the state” through technique also means that just as this integrating entity is political, it also integrates production and consumption as well as entertainments and leisure satisfactions. A revolt against the administrative state is also a revolt against industrial production, mass consumption and the many forms of the entertainment and leisure which distract and occupy us.

“By challenging technology we also challenge the affluent society (i.e. a society possessing an excess of material things, theoretically useful, but unassimilable and ultimately overwhelming, providing human beings with immediate pleasures and satisfactions, but also with a false sense of achievement by stifling their ambition) and, to an even greater extent, the consumer society, in which all things are regarded as articles of consumption; acquires a value and meaning as well as justification—the consumption of religion, of leisure, of revolution, for example.”

The administrative state and its regime are built on a cultural set of values centered around technique and technical thinking: technology, industry, science, production, consumption and the modes of living dictated by these various aspects. The administrative state is the form of government made suitable for a technical, industrial and scientific society. Without those underlying modes of thinking and doing, there is no administrative state. At the same time, if you challenge the administrative state, you must challenge all its supporting pieces. At the same time, the system cannot be bent to ends that are not technical. If we try to plug in a differing ideology, such as conservatism, or populism, or even fascism, into the technical system, it will be integrated into it and become, in the end, technical. If this alternate ideology succeeds in making the system more efficient or even more accountable, it in end only strengthens the system as a whole. The only way to challenge the regime is to challenge the system as a whole. You cannot do so in a half measure. The challenge must be total.

“Nothing short of an explosion will disintegrate the technological society. … It will involve a sacrifice.”

It is at this point that I believe Ellul undersells its effects. He talks about a reduction in the standard of living, a reduction in public programs, the erosion of mass culture and a decreased efficiency in all areas. I am not sure how one plans to explode the system and keep anything. Exploding the technological system which underpins the administrative state which is the source of regime power, I would argue, moves us into the “billions must die” level of catastrophic impact.

And while I agree that Ellul is correct that the administrative state regime cannot be meaningfully challenged without bringing down the whole system, I cannot bring myself to make the argument that the ends justify the means. His own observation, made at multiple points throughout the book, is that the average man does not wish for revolution. Faced with its reality, the costs to him are too high. The potential for suffering is too great. As with many of the plans of the elites or the wizards of smart, their cost is largely born by the common man. The wealthy, privileged and powerful often seem to emerge from the other end of these catastrophes relatively unscathed.

So what do we do? We have to recognize that the regime system is fragile and that the system is not really designed to deal with the true “exception” for which it cannot account. Also, I think something less apparent in 1969 when Ellul wrote this work, is that the system has already reached its zenith and is in decline. It is struggling to provide the satisfactions that were there for everyone in the 1950’s and the 1960’s. Covid-19 exposed many of the fragilities in the system. This is not to say that the administrative regime will not try to integrate every challenge into itself and assert an ever greater level of control over all things. There is a good chance that the regime collapses and fragments. There is also the strong possibility of a long, slow torturous decline.

Again, what do we do? In this regard, I think the most fruitful avenue is to build a parallel polity, which, as much as possible, is able to be a refuge from the regime as well as something that is free from the integrated reward structure of the regime. It must be able to administer itself without resort to the technical. I would rely on the ability of persons, holding them accountable for their actions. It would develop and rely upon oral tradition, a culture of law that is embedded in custom and culture, not paper and institutions. Its relationship to technology would have to be organic and grounded, not abstracted, rationalized and systematized. In a sense, Ellul is correct that this community would have to be built without a plan in place, but rather on a set of values which put mankind and community ahead of machine, technique and system. It would be embedded and organic, mostly passed on through word of mouth and physical demonstration.

As I have written elsewhere, earlier in this series and in other pieces, because the administrative state asserts a metaphysical role, it assumes the place of a god. In that regard, this is a spiritual, a religious fight: a clash of gods. Because the technical system is fundamentally western, in spite of its spread over much of the world, if it is going to be resisted by a parallel polity, this must grow up from within. That means the Christian faith must rise to challenge. I believe all the tools are there within itself. Christianity was intentionally founded to be a faith community which exists alongside the regimes of the land as a parallel nation. This is who we are. So rather than try to capture and control a regime structure which will likely subvert and integrate the Christian faith into itself, we should build a community, a polity, a set of institutions that are unquestionably our own, run our way by a completely different set of values other than rational abstract technocratic planning. We seek the Lord and his power. And with his power, we build. We strengthen. We gather. We become a refuge for those looking to escape the demands and logic of the regime. And we wait. Chances are, the regime will see us as the threat we are and will lash out. Conflict will likely result. Then, perhaps, Ellul’s counter-revolution will come. The system will fall. Hopefully we will have the strength and capability to pick up the pieces and mitigate the catastrophe. Perhaps this passage from 2 Corinthians 6 will encourage us as we set ourselves to this task:

14 Do not be yoked together with unbelievers. For what do righteousness and wickedness have in common? Or what fellowship can light have with darkness? 15 What harmony is there between Christ and Belial? Or what does a believer have in common with an unbeliever? 16 What agreement is there between the temple of God and idols? For we are the temple of the living God. As God has said:

“I will live with them

and walk among them,

and I will be their God,

and they will be my people.”17 Therefore,

“Come out from them

and be separate,

says the Lord.

Touch no unclean thing,

and I will receive you.”18 And,

“I will be a Father to you,

and you will be my sons and daughters,

says the Lord Almighty.”

This has always been the way. It is a challenging path to refuse the rewards of the regime, to set ourselves apart and make ourselves a target. And while we may still be early in this process of learning, teaching, gathering and building, the hour is growing late and our time is getting ever shorter.