Humility: A Key Virtue of the Post-Liberal Order

Humility is one of those traits of good character we are told we need to cultivate, but our egalitarian society makes it almost impossible. It will be vital for a post-liberal world.

Now Moses was a very humble man, more humble than anyone else on the face of the earth. Numbers 12:3

Today, we read a passage like this and we have no idea what to do with it. What could they possibly mean by this? It is hard for us to picture a man who went up a mountain and met God as “humble.” Was he self deprecating? Was he shy? Did he put himself down? Did he make himself smaller? Did people push him around? Our culture makes a proper understanding of humility almost impossible, so much so that it’s almost an alien concept to us today. I am going to propose a definition which I picked up along the way and has served me well. But, when I work through the implications of it for people today, most end up rejecting it, in large part because our culture makes it hard to grasp the idea of humility. This inability, I would argue, contributes to many of the problems we face today in our society.

So how would I define humility?

Humility is being able to see ourselves as we are, no more, no less.

With this definition in hand we can begin to unpack its implications. Let’s ease into it with the low hanging fruit. Right off the bat it kind of has a nice feel to it. Yes, we think. No one should think too highly of themselves. Neither do we want people trying to diminish themselves. Pride is one of the seven deadly sins, so not thinking too highly of yourself is a good thing. But people can also try to justify beating up on themselves, tearing themselves down, depreciating who they are and their value in some vain attempt not to seem too proud. So, yeah, that seems good. Just see yourself as you are, not more, not less.

Let’s shift the scene a little. You are a gifted athlete. Very gifted. You play a team sport. You are by far the most talented person on your team. You look at yourself and, seeing yourself as no more or less than you are, seeing yourself exactly as you are, you tell yourself: “I am the most talented person on this team.” So now that you have seen yourself clearly, and with true humility, what do you do with this knowledge? Do you lord it over your team mates? Do you make a point of belittling your team mates for their lack of talent? Do you try to hide or shy away from your talent, holding back so as not seem better than your team mates? Believe it or not, this last thought is a real problem when coaching women’s sports. Girls don’t like to stand out and be thought of as better than their team mates. They will underperform relative to their talent so as to appear no more talented than the others. Boys, on the other hand, who tend to focus on dominance, hierarchy and the pecking order of one up/one down will tend to lord their talent over others. So what is the correct response?

How do you acknowledge who you are, as you are? How do you embrace and live out a proper humility? It is a hard thing to sketch out with words, but it is the kind of thing that we know when we see it. Acknowledging that you are the most talented player on the team means accepting that with this tremendous athletic ability comes great responsibility. You may not want this responsibility. You might prefer to be just one of the guys, a role player. But, your ability has thrust you into a role that you must now accept. You must become “the star player.” This role touches deep currents, archetypes, that you must embrace if you are to be who you are, no more, no less.

You must shoulder responsibility. You are the guy expected to have the ball in your hands in the crucial moment of the game. The spotlight will be on you. All of the glory. All of the crushing heart ache. You must be the emotional spark of your team. You must be its driving energy. You must be an example. First in the practice facility. Last one to leave the building. You work harder. More film study, more reps. When others are down, you do not give up. You fight to the end and carry the team on your back if you have to. You will try to elevate the play of your team mates, and carry them with your ability when they are not capable of stepping up. When they succeed, it is your job to praise your team mates, to lift them up and notice their contributions. Yes, you will likely have no choice but to talk about that final game winning play, but you will do so in a way that sees it no more or no less than it was. Your team mates will feel that they are more by playing with you than if they played on their own. You will take responsibility for the losses. You never throw your team mates under the bus. We know this kind leader. It is the man people follow. They would play through a wall for him. He is who he is, no more, no less. He is the star of his team. There are rewards. There are responsibilities. The two come together. The true star player is who he is, no more, no less. He embodies the archetype.

Hierarchy and Equality

This idea, fundamental to the heart of Western enlightenment liberalism, is that everyone is equal. We have various ways that we define what we mean. Everyone should be equal before the law. No one person should have more influence on the system than any other person as embodied in the idea of “one man, one vote.” We should all have the same equality of opportunity. Some carry this farther and argue that there should be an equality of outcome. But we find this idea working itself out in strange ways. If we are all equal then what really matters is how hard you work. Everyone, if they work hard enough and make good decisions, can succeed if they desire it. Because all people are equal, it must be that the one who succeeds did so because of some virtue in their actions. They pulled themselves up by their own bootstraps. This is as much a part of the philosophy of the enlightenment liberal idea of equality as is those who believe in affirmative action. It is two sides of the same underlying worldview.

But most of us know that we are not all equal. There are sex differences. There are differences in appearance, intelligence, skill with one’s hands, communication ability, athletic ability, opportunity, social standing and situation, religion, attractiveness, height, build, ethnicity, and race. We are not uniformly the same person. We are not all interchangeably equal with each other. We are not all equal before the law. We are not all born with the same opportunities. So in an egalitarian society, we are not permitted to see ourselves as we are. We must pretend to be equal with others. Humility, as we encounter it today in our egalitarian society, is a kind of falseness where we pretend to be equal with everyone else. There is also an aggrieved sensitivity to the idea that one might be somehow less than another person. It is an offense that someone might even hint that somehow, in some way, they are better than us. We find the idea offensive, off-putting. So we set about to pull people down to our level, to make them just like us, to “humble” them. There is a word for this in the classical lexicon of sins: envy. Our desire for equality makes envy run rampant among us.

Our society can permit no natural hierarchies. Perhaps the one exception is the arena of sports. But even here one must tread lightly. Generally, though, we permit no real greatness. As a result, even in the churches we are not allowed to have saints among us. We tell ourselves that we are all the same. We are all “sinners before an angry God.” Each of us has the same status. We have so polluted the idea of “grace” that we struggle with the idea of someone growing close to God, of someone meeting God in a way that we do not. That person who raises their hands in worship must be mocked behind their backs. The group that wants to start a revival must be pulled back into line. We can’t have any saints here. No one else’s saintliness should be permitted that would make me feel embarrassed about my own spiritual condition. Thus we engage in a quiet conspiracy to all be equal. No one rises above the other. We all have an unspoken agreement to live a kind of bland goodness, evidencing behaviors that might be a little better than the non-Christian, but not so much so that anyone would feel the need to pull us down and put us in our place again. And we wonder why churches are emptying out. If people in the churches are more or less just the same as everyone else, why bother?

Outside the churches, we enact all kinds of policies that allow us to whitewash any superiority that might cling to us, thus sanctifying our achievements. The policies of affirmative action allow us to pretend that everyone who got into Harvard did so because they worked hard and were given an equal opportunity as everyone else. I got in, not because of some accident of birth, but because I had the virtue to make the most of the equal opportunities given to all fairly. The language of equality allows me to feel good about my innate advantages in intelligence, upbringing, social standing or what not. But not really. The truth is known, but cannot be talked about. We are not permitted to be humble about our success, to see ourselves as we are, and thus to accept the responsibilities which come with it. All we are permitted is a gnawing unresolved guilt.

At the same time, this idea of equality gives us the impression that we can all be what we want to be. After all, as the trope goes, anyone can grow up to be president of the United States. All you have to do is work hard and apply yourself, follow your dreams and you too can be a success. If it doesn’t happen, it is easy to look away from one’s self. My lack of success must be the fault of an inherently unjust system. No one stops to realize they were never going to be president and this possibility was never open to them. Just like you are never going to be the star of the team because you are an awkward skinny kid without any coordination or real real athletic ability. In an egalitarian society we cannot accept the idea that each person in society has a role and a place. In contrast, in a hierarchical society, wellbeing comes from accepting one’s place and being the best at one’s role in society that one can be. Instead, egalitarianism fosters an anger against “the system” for holding us back and limiting our potential. The system must be fixed so that anyone can be anything they want to be. So we find ourselves today in a society that promotes guilt, envy, anger and pride in the quest to maintain the fiction that everyone is born equal.

But, But, I Thought Christians…

There is this unfortunate misunderstanding that Christianity as a religion fosters the exact kind of corrosive equality we have been talking about about above. This comes from an unfortunately superficial reading of a small handful of texts without placing them within a wider theological context. Texts like this one:

“Here there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all.” Colossians 3:11

Or this similar passage:

“There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Galatians 3:38

For someone raised in a culture steeped in the ideas of liberal egalitarianism, this seems to be telling us that the Christian message is that all people are basically the same, they are all equal. This could not be farther from the truth. These passages are not telling us that in Christ all of these differences are now erased and that within the Christian community everyone will be now finally be equal. No, they are telling us that all of the old hierarchies, all of the old labels you used to use to sort yourselves out now no longer matter. You are leaving behind all of your old labels. As I have said elsewhere, once you are “in Christ” you are first and foremost a Christian above all else. You are not an American Christian. You are a Christian who happens to live in America. The community of Christ is your true home. When we commit our lives to Christ, we let go of all the old hierarches and allegiances, embracing a new set of hierarchies with Christ as our Head, our King, our Lord. You are not first of all a Jew or a Greek or a Scythian. You are not committed to men’s issues or women’s issues. No masculinists or feminists in the kingdom of Christ.

It is a subtle concept, sure. But letting go of old allegiances does not erase where we came from or our gifts or unique characteristics. The faith is still incarnational and not abstract. That means it is lived within a world with wild amounts of uniqueness and variance. But all that uniqueness and variance is re-ordered around a new organizing principle, that of the Kingship of Christ. Everything flows out of and relates back to this. It is a change at the level of our “being.” “In Christ” we enter a new mode of being, and it from this new mode of being that our unique characteristics are expressed. Who I am as a man or who someone is as a woman is now subservient to Christ. All the unique characteristics that make me a man are now under Christ’s dominion. Same too, the cultural characteristics of my race and ethnicity and the unique characteristics of my people. They no longer serve the people. They are now in the service of Christ. These unique characteristics now express themselves in and through the new being I have “in Christ.”

This new being does not erase the idea of a hierarchy of being. The same canonical author, the Apostle Paul, also wrote this, and I quote it in its entirety for the full impact:

“ 4 There are different kinds of gifts, but the same Spirit distributes them. 5 There are different kinds of service, but the same Lord. 6 There are different kinds of working, but in all of them and in everyone it is the same God at work.

7 Now to each one the manifestation of the Spirit is given for the common good. 8 To one there is given through the Spirit a message of wisdom, to another a message of knowledge by means of the same Spirit, 9 to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by that one Spirit, 10 to another miraculous powers, to another prophecy, to another distinguishing between spirits, to another speaking in different kinds of tongues, and to still another the interpretation of tongues. 11 All these are the work of one and the same Spirit, and he distributes them to each one, just as he determines.

12 Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. 13 For we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body—whether Jews or Gentiles, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink. 14 Even so the body is not made up of one part but of many.

15 Now if the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. 16 And if the ear should say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. 17 If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? 18 But in fact God has placed the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. 19 If they were all one part, where would the body be? 20 As it is, there are many parts, but one body.

21 The eye cannot say to the hand, “I don’t need you!” And the head cannot say to the feet, “I don’t need you!” 22 On the contrary, those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, 23 and the parts that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor. And the parts that are unpresentable are treated with special modesty, 24 while our presentable parts need no special treatment. But God has put the body together, giving greater honor to the parts that lacked it, 25 so that there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other. 26 If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it.

27 Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it. 28 And God has placed in the church first of all apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then miracles, then gifts of healing, of helping, of guidance, and of different kinds of tongues. 29 Are all apostles? Are all prophets? Are all teachers? Do all work miracles? 30 Do all have gifts of healing? Do all speak in tongues? Do all interpret? 31 Now eagerly desire the greater gifts.”

Throughout this passage there is a clear recognition that God, through his Spirit, gives people different gifts. They all come from the same Spirit and are all part of the same phenomenon. They are all part of this “good news” in Christ. But these differences in gifting create different roles. Some are the head, the brains. Some are the eyes, they see. Some are the feet, they walk. But some are also the private parts. Each has their role. Each has their place. As Paul says, you should desire the higher gifts. But remember, they are gifts and the one you desire may not be given to you. But that is ok, you have your place and you are an important part of the body. To loop back to the sports illustration we started with, someone is the star player. Someone is the role player at the end of the bench. You are on the team and you have your role. The role God gave you. So embrace this role.

This is also how there can be differences related to things like gender or ethnicity. There are certain things men do well. There are certain things women do well. Getting away from the leadership question—although I do think this is primarily a men’s thing—men generally like to pursue the truth without regard to feelings and women generally value the importance of relationships and how people feel over other concerns. God is quite capable of using the unique characteristics of various ethnic groups in his service. He is also on record for overturning our human hierarchies to make the point that he is King and his hierarchy matters more than human evaluations. He gives divine wisdom to those the world considers foolish. He will make the youngest son king. The important thing to remember is that being “in Christ” does not erase hierarchy; it gives us a new hierarchy ordered around Christ’s Lordship of all things.

The Burden of Being Better

I am going to stick with the Christian situation, largely because even though I think humility needs to be a key virtue for all of society, it is an issue that arises out of our culture’s interaction with the Christian faith. Rooting it in its proper context helps us understand it correctly. So, we ask in this next section, “Why would someone become a Christian?” There is no one answer for this and motivations vary, but in the main, conversion usually comes as a result of confronting the disorder, sinfulness, folly, emptiness, purposelessness, or lack of meaning in one’s current situation. For most, broadly speaking, they see a lack in their current life that they hope will be addressed by becoming Christian. Basically, the vast majority of people become Christians because in some form or another, they want to be better people. You certainly don’t become Christian so that your life will remain exactly as it was before. If that were the case, why would you bother?

But this creates a dilemma in an egalitarian society. You have become a Christian to be a better person. So, lets say it starts to happen as you hoped when you made your commitment to Christ. You are now a better person. It feels great. Now you have a problem. You are conscious of being a better person. This is exactly what you wanted. Its everything you hoped it would be. But what about those people who are not Christians? We are so spooked by passages like this that we really don’t know what to do:

“ 9 To some who were confident of their own righteousness and looked down on everyone else, Jesus told this parable: 10 ‘Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. 11 The Pharisee stood by himself and prayed: ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people—robbers, evildoers, adulterers—or even like this tax collector. 12 I fast twice a week and give a tenth of all I get.’

13 “But the tax collector stood at a distance. He would not even look up to heaven, but beat his breast and said, ‘God, have mercy on me, a sinner.’

14 “I tell you that this man, rather than the other, went home justified before God. For all those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.’”

Many read a passage like this and come away with entirely the wrong message. We must model ourselves after the tax collector. We must forever remain, “the sinner.” We are not allowed to get better, because to us becoming better means becoming like the Pharisee. But at the same time, if somehow we do become better, heaven forbid we give any evidence of it or admit to ourselves that we are better.

So what is really going on here? It is a parable about getting in the door. The person who is willing to admit they need help, like the tax collector, can get in the door, because they are willing to receive God’s mercy. They know they need it. The other man has no need for God, because he has his life together. It is all about him and what he has done. His talking to God is performative. He does does not really need God. The tax collector was able to see himself as he was, no more, no less. The Pharisee had an elevated, misguided sense of his position with God. He could not see himself as he was.

Once in the door, though, most of us are deathly afraid of wanting to appear like the Pharisee. This is because we misunderstand humility and the nature of the spiritual journey. So we come up with fictions (that inevitably become reality) like “I am just a sinner like you” when we talk with non-believers. We completely deny the testimony of God’s grace at work in our lives. We are terrified of being better people, or at least of someone thinking that we might aware of the fact that we have become a better person. So we perpetually pretend that we are just like the unbeliever, but we have grace. The message is that me and my life are no different from you and your life, but I have Jesus. But if that is the case, does Jesus make any sort of difference in your life at all? You know that he does, so why can’t you acknowledge this to yourself and to others? In large part, our culture of equality won’t permit it.

But the essence of the spiritual journey is learning to grapple with the burden of being a better person. Any time your life will begin to reveal more fully who you are “in Christ,” any time your journey on the path of life takes you to a new plateau, after making the climb, the first temptation is generally to look back and feel good about yourself. You will, like the Pharisee, be tempted to give yourself the credit. You will be tempted to look your nose down at those on the plateaus beneath you. The hardest thing to do is to graciously accept that you are where you are. Being here comes with rewards. You have a closer, more intimate relationship with God. Your life is better ordered according the ways of Christ. But it also comes with a host of responsibilities. One is to be saintly. You must be who you are. There is that perpetual temptation to be pulled back down and become “one of the guys.” No. You are no longer one of the guys. You are more sanctified, more deified, and this is a good thing. You must be an example. You are now the star. In an egalitarian society, the envy of others will mean they will be constantly vigilant for hypocrisy or failings in your life so they can then pull you down off the plateau. This will give them an excuse for not making the climb themselves. You are now the star player. First in, last out. You carry your team mates. But you can only be the star by being humble enough to see yourself as you are, to acknowledge the responsibility of being “the saint.”

The Political Implications of Humility

This is easier to see and to sort out in a unified community like the church, organized under the banner of Christ. But what happens when you get out into the world? In a relatively insular, culturally unified community, it is easier to accept this idea of hierarchy and roles. It is easy to see that the role of the king, the prince, the ruler, the governor, the elder, the chief, the president involves a web of responsibilities and burdens that come with some privileges as well. In a flourishing society the ruler is expected to have a burden for his people such that he works to lift up the downtrodden in his care. It’s not a matter of handouts, but of making that guy at the end of the bench a better player. It’s about finding a role in society for as many as possible, all of them if it can be done. As king you shoulder the burden for the team. This is essentially the Biblical idea of kingship.

This is why the idea of divine grace, divine mercy, is so important. In my faith tradition we have this idea of “special grace” that comes to us through the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. There is also “common grace,” common mercies. In a world that lives under the effect of human sinfulness, a world where evil exists, to be born into a position of privilege is a form of grace. It is a gift from God that comes with responsibilities. To be born with intelligence, athletic ability, skills with your hands, a stable family situation, especially a Christian family, are all gifts from God. This also means that you are born into a role. It means accepting the gifts that have been given to you and the role those gifts thrust upon you.

So how do you respond? With thanksgiving of course. And with humility. You acknowledge the gifts you have been given. They come from God. You are a steward of these gifts. Whether they are personal, natural gifts or something more supernatural, they are all gifts. The correct response to any gift is thanksgiving. You acknowledge and recognize the gift that has been given to you. You will likely have to grow into a full awareness of the gift you have been given. But in humility, you acknowledge who you are, you accept the gift and make it your own. You become a steward of the gift. So the best way to say thanks is to maximize the gift through your effort. The work you do to maximize your potential is a prayer of thanksgiving to God for the gifts he has given you.

The idea of equality tells us that as long as we all have the same opportunities, each of us is responsible for our own successes. There really is no grace. There is no gift. After all, we are all equal. There is just my hard work. My only responsibility to my fellow man is to ensure that the system is as fair as possible so everyone has the same opportunity. Because we have denied differences among us, that there is a hierarchy of differences among us, we do not feel that any personal obligation comes with our position and standing in society. We are not fitting into a role. There are no personal obligations that come with my successes.

We tend to know this is a lie, though, because so many of us feel guilty about our success, in part because we cannot acknowledge it and the responsibilities which would then come with it. We can’t say, “I am the star of this team.” And so, living in denial, we try to assuage our guilt through attempts to fix the system. If we can just give everyone the opportunities we had, then everyone will have a fair chance at success. This will justify our successes to ourselves. What we can’t say is that this other person was never going to succeed. They just lack the capacities I was given. And because we cannot say this, we cannot embrace the responsibilities that come with our ability or our success. We cannot shoulder the personal moral responsibility of being their caretaker. Our society suffers because the successful have been released from their moral obligation to “the downtrodden,” to lift them up.

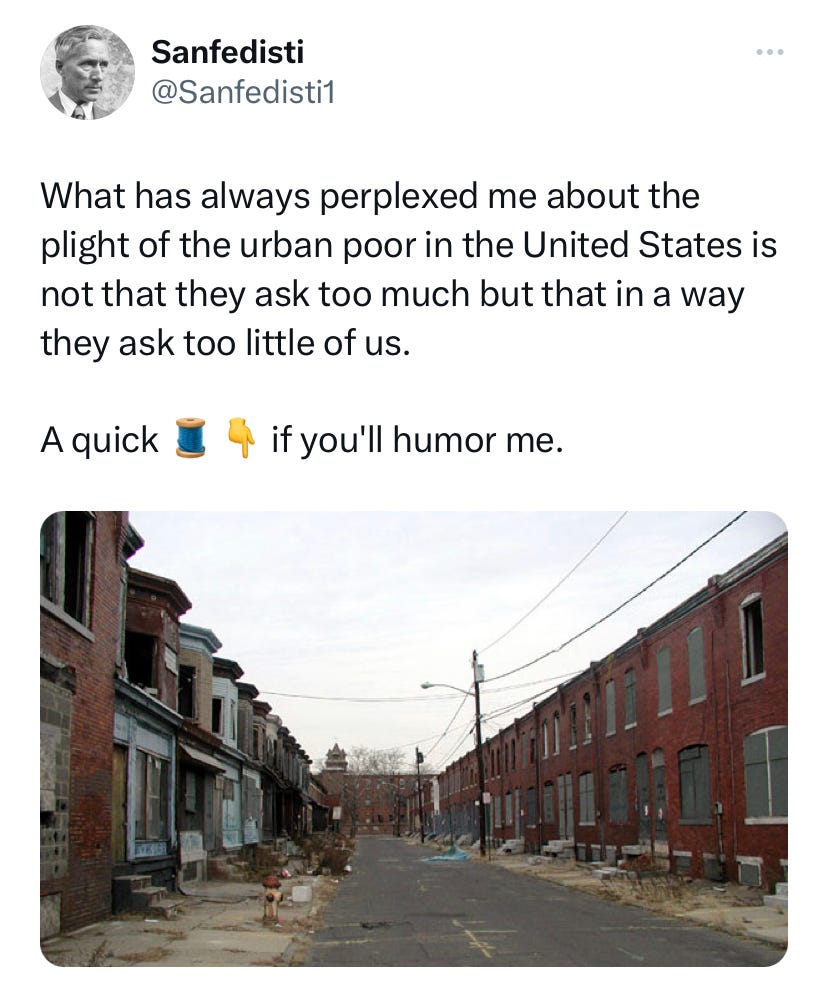

And so it is easier for us to become exploitive. Once that personal moral responsibility is severed, once I no longer have to accept the role of being one of society’s princes, even if I myself don’t think I personally exploit others, it is easy to ignore how those relationships of responsibility and obligation get severed one by one. We turn a blind eye as a local business owner takes his company public, severing the direct bond between ownership and the workers. We turn a blind eye when that factory is moved overseas and all these people lose their jobs. We tell ourselves there are lots of opportunities. They just have get re-trained, maybe move and they can find work elsewhere. Once you lose sight of the humility that comes from understanding the graces you have been given and the obligations they create there is a domino effect. They tip one by one and then one day you end up at a place like this and wonder how you got there:

He is right. They do ask too little of us, in part because of our inability to be humble, we cannot accept the personal moral responsibility we bear for the condition of these places. We refuse life’s hierarchies, the gifts that God has given us and so we refuse the responsibilities that come with those gifts. We enjoy the rewards. We feel the guilt. But we feel helpless because we believe that somehow “the system” will fix all of these problems and absolve us of the moral responsibility that comes from being the star of the team. We cannot acknowledge that we are the star players in our society and, as a result, we have not elevated and made our team mates better. We cannot be nobility. And it shows everywhere throughout our society.

What we have done locally, we have also done across the globe. We have built a world spanning commercial and political empire. We are the powerful, conquering kings. We are the world’s star player. We are it’s new nobility. But, for the most part, we have denied this role. We don’t want to acknowledge who we are. Because of our egalitarian ideology, we must pretend that people everywhere are all the same. Past empires, the Greeks, the Romans, Colonial Europeans, saw themselves, in large part because they were the conquerors, as superior peoples. They were able to acknowledge that they were the star players. They imposed their culture and society upon the conquered lands. They were often paternalistic, seeing themselves as caretakers who had a moral obligation to “civilize” societies which they viewed as “inferior” or “primitive.” Today we would label these colonial practices as “racist.” However imperfectly they saw themselves—was it true humility?—there is no doubt that they saw a hierarchy of civilizations, with theirs at the top of that order. As a result, they took it upon themselves to elevate the other cultures. It was often brutal, exploitative, and condescending, but they understood the role which had been thrust upon them as conquerors. They were the globe’s star players whose obligation was to elevate the play of the peoples who now were under their control.

Today, in a post colonial period, we are now loathe to admit any form of superiority at all. We want to believe all people are equals and thus all people groups are equal as well. But we still exploit the weaknesses of others for our own gain. This is what empires do. But as we have expanded the empire we have carried with us this idea of the equality of all people. So we think that if these people adopt the same philosophy and political ideology as us, they too will soon be just like us. On the one hand we try to spread the idea of egalitarian liberalism, but we try to do so in a manner which is non-paternal. We are loathe to admit that we are the world’s princes, that we are the star player in the world. Everyone just needs a few seminars in equality, diversity and inclusion, to be shown how to build western style technocratic administrative systems and they will be good to go. They don’t need a caretaker, we tell ourselves.

But what if they are not just like us? What if there are differences between us that become evident very quickly once we start interacting these other people groups? What if there are very good reasons why we were able to conquer them? Albert Schweitzer once said:

“I have given my life to try to alleviate the sufferings of Africa. There is something that all white men who have lived here like I must learn and know: that these individuals are a sub-race. They have neither the intellectual, mental, or emotional abilities to equate or to share equally with white men in any function of our civilization. I have given my life to try to bring them the advantages which our civilization must offer, but I have become well aware that we must retain this status: we the superior and they the inferior.”1

We are not “allowed” to say these things in an egalitarian society. They are considered racist. It is a very strongly worded paragraph. Living in our egalitarian society, we all feel the urge to condemn Schweitzer for his words. But what if they are even partially true? Even speaking them obliquely, through the lips of someone else, causes shudders and nervous looks. You just don’t say such things. They are taboo, verboten. We are all equal. Yet, in some sense, the fact that the West conquered and has been able to exploit Africa and Africans, as well as multiple other people groups across the globe, does tell us something. But our egalitarian sensibilities no longer allows us to accept this message. And so, in humility, we cannot accept our role as princes over a conquered people. We are not allowed to say, “We are the best player.” As a result, we are not permitted to see things as they are. We forbid ourselves from taking up the burden of humility. Because of this, we cannot acknowledge that we are the globe’s star players and it is our responsibility to elevate the play of the new team mates at the end of the bench whom we acquired by force. Instead, we exploit their natural resources. We exploit their labor. Just one example to illustrate: the cobalt mines in Congo supplying the materials that go into our precious cell phones. They call them “artisanal mines.” Child labor. Brutal conditions. $2 a day.2

We use them as cheap, virtually slave labor. But we are able to ignore the direct moral responsibility we bear because we are not allowed to be humble, we are not allowed to see ourselves as we are and accept the moral responsibility for who we are. We cannot say, “We are the world’s princes.” “We are the star of the team.” And because we are not allowed see ourselves as we are, we not able to embrace our role as the world’s caretaker. True humility is forbidden to us. We have built this empire, conquering at the tip of the gun and in the arena of commerce. But our egalitarianism prevents us from taking responsibility for those who are under our dominion. We tell ourselves that we are entering into trade agreements with equals. And so we turn a blind eye, exploiting the people who should be in our care.

Would our humility fix all the problems under our dominion? No. We live in a sinful world where evil abounds. At best, all solutions can only ever be partial. But we do ourselves real moral, spiritual, physical, material, and social harm because we forbid ourselves from acknowledging the hierarchies all around us, seeing them honestly in ourselves and others. Because we cannot do this thing, because we cannot acknowledge that we are at the top of the world’s hierarchy, we are its princes, we cannot properly accept the moral responsibility of our role and position in life, as persons and as a society. Because we cannot say, “I am the best player on this team,” we also cannot accept true moral responsibility for our team mates.

From: https://www.crisismagazine.com/opinion/looking-down-on-africa

https://abcnews.go.com/International/cobalt-mining-transforms-city-democratic-republic-congo-satellite/story?id=96795773 and https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/drc-mining-industry-child-labor-and-formalization-small-scale-mining

Your piece is a refreshing antidote during the current month-long celebration of pride. Thank you.

In the 1980s, the US military engrained in its officer candidates the burden of leadership. I assume that's no longer so, and any previously trained officers are probably long gone.

Feminism has certainly drilled the humility out of women. I see it particularly in relationships between women. Ordinary differences devolve into catfights because neither party is willing to embrace humility.

I am reminded that during my catechesis the priest, Fr. Haas, and I were talking about humility and he brought up that it is rooted in earth or soil. As you say - being humble is being down to earth or knowing who and what we are and what we are capable of without debasing or deprecating ourselves nor engaging in hubris.

Is the mountain haughty in its heights? Does the sea despair of its depth? Neither should each man hold themselves as being above one another but understand their role and embrace it.

"You will, like the Pharisee, be tempted to give yourself the credit. You will be tempted to look your nose down at those on the plateaus beneath you."

A poignant reminder that we are to remain fixed upon Christ and that we are all running our own race, and that we are not called to quietly live and let live but to let Christ shine through us and our lives as living examples (which is what I was thinking about writing this weekend anyway so probably yes it is what I will write about).