Credentials: the Simulacrum of Wisdom and Authority

There is a crisis of legitimacy today in our elites. Their authority is evaporating and they don't really understand why. They increasingly rely on credentials as a substitute.

We are obsessed with credentials. The very highest ranks of our society are almost all educated at a handful of so-called elite universities, the Ivies, or their near equivalents. This mania is not limited to just the high achievers among us. Every field of work now has certifications one must earn and display to show competence.

This is a problem for our society. A crisis, actually. Why do people look to credentials? They want some way to ground knowledge and truth that is not depended upon the person. This is an old, old problem. What is Truth? How should I act? What should I do in this situation?

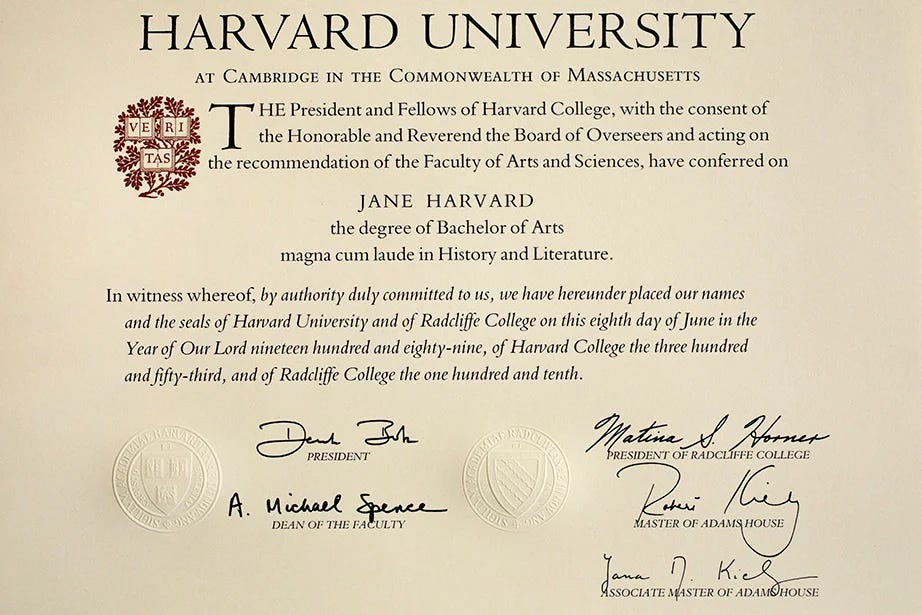

This mania for credentialing exposes a reality that most of us would rather not examine too closely, especially conservatives and Christians. The bottom line: there is no sure basis for knowledge and truth that is not dependent upon the vagaries of us as knowers. The idea of the credential is that it “grounds” the opinion of the expert in something outside of the expert. It is meant to say to us, “We can trust this person’s declarations because they have a degree from Harvard.” The degree “grounds” the opinion.

Modernity attempted to sweep aside what they thought was an older order of superstitious knowing replacing it with the sure knowledge of reason and science. But the truth is that science cannot ground knowledge. There is nothing outside the human person that can form a sure basis for knowledge and truth, taking all of the quirks of human opinion out of the question. This is in many ways the quest of modernity since the enlightenment. It has been a failure. There is no sure way to ground knowledge and there never will be. There is no real way to escape the reality that we need wise men to guide us.

One of the challenges of our time is that we are almost constantly in denial of the nature of knowledge and knowing. The old way was to say that truth was God given. Along side of this, it was argued that God wove into the very fabric of creation a metaphysical order. What is this metaphysical order? It is something super sensory. It lies beyond our senses and thus our ability to observe, quantify or measure it. It a thing beyond the reach of science and yet orders all that can be perceived with our senses. You could call it a supernatural reality. This is the realm of the Forms, and more.

To many, these realities seem obvious. To others, materialists in particular, as well as many non-materialist atheists, these categories are largely nonsense to them and they argue that the word of God or things metaphysical cannot form the basis of human knowledge, cannot form the basis of truth. Perceiving these realities is largely intuitive. Even if you say, “Listen to the voice of God,” how does God speak? He speaks to people (theophany) or through persons. When push comes to shove, we must trust the person who utters these words: “Thus says the Lord…” We must trust the person who “sees” the deeper realities, the greater wisdom that lies beyond sight, that cannot be observed directly, cannot be measured, and is often difficult, sometimes even impossible, to put into words.

The Bible, as the written word of God, adds another layer. Not only do we have to accept that the men who wrote it spoke on God’s behalf, but we must also trust those who interpret the words of God and tell us what it means. Through the first half of the history of the Church, it was the bishops and the institution of the church who acted as the guardians of the best way to interpret the scriptures. But what do you do when that institution becomes corrupt? The Reformation solution was to democratize the process. Each of us becomes our own wise man, reading the word and working out for ourselves what it means. It was also argued that the truths of the bible communicated a plainspoken universally true literal meaning. It seems like a simple solution. But what of metaphor and poetic imagery? The bible itself claims that the deepest wisdom is “unknowable.” It is also claimed that the metaphysical truths broadly perceived in the world were self-evident to all. But are they? If I am tasked with sorting out for myself the truth, the Truth, how do I know that I am right? The problem remains.

The scientific revolution was an attempt to get away from this problem. We will base knowledge on what can be observed in nature, what can be measured and quantified. We will confine ourselves to focusing on how things work and how we can harness the forces of nature to our benefit. This was immensely powerful, but it still did not make the problem of knowledge go away. Most times, having understood the “how?” we still have not answered the question, “What is the right way to act in response?” That aside, even sticking to question of “how” there is no way escape the role of the observing person in the role of scientific observation. What should I observe? This is a human choice. And the mere act of observation, as Heisenberg has demonstrated, when applied to the smallest particles, determines their state. In the act of measuring particles, you determine if that particle has a vector or a wave. Your act of measuring determines its “truth.”

What this means is that we still need wise guides, we need the seer, the prophet, the priest to tell us what things mean and what we should do. We need “authorities.” The problem is the same as it always has been. We need people to tell us the will of God, so to speak. We need people who can “see” the Forms. We intuitively sense this because we instinctively go to the people with the credentials to tell us what to do. But having a credential is not the same thing as having real “authority.”

On the one hand it is kind of gauche to have to mention one’s credentials. No one really wants to have to say, “I went to Harvard, therefore you must listen to me.” I know myself that if a disagreement has devolved to the point where I have to tell someone that I have an advanced degree in philosophy and theology and therefore I know what I am talking about, it is already a fail.

And yet these credentials are the basis of our society’s authority system. Things today are just too complex to weigh the wisdom of every person we meet. So, we use credentialing as a substitute, a way to ground authority in something outside the person. The problem is not that we are expected to listen to experts or the wisdom of authorities – there is no way around that, none—it is that the credentialing system cannot adequately evaluate the wisdom of every credentialed person. As a result, we have a credentialed class that gives terrible advice, mostly because our wise men are generally not very wise.

Because we lean on credentials, not the person, this habit of fobbing off responsibility is endemic. Instead of leaning on the wisdom of the wise, we turn not just to credentials, but also to “the process,” or “the science,” or “the study,” or some such. We have an expert class who wants to be able to reap the rewards of the wise man, without having to bear personal responsibility for their advice. So, we marinate in mediocre, or downright terrible, counsel. No one ever pays the price for bad advice. They do not lose their heads. They and their families are not ruined because they are stripped of all titles and privilege. There are no real consequences for foolish counsel. More than ever, we need wise seers to advise us, to read the signs and tell us, “Thus says the Lord…” but they are largely unwilling to step forward, own, and take responsibility for their expertise, that the future of our society is on them as persons. And because of the general atheism and materialism endemic among our leadership class, they are loathe to even admit the reality of such forms of knowing. They have embraced “scientism,” making the argument that if it can’t be measured or observed, it isn’t really knowledge. They close themselves off to the only sources of wisdom while claiming to be our wise guides, the experts. And so, we are a society with the appearance of wise leadership, but without its reality.