Actually, The Things You Do in Your Bedroom Are Everyone's Business

Building on my post from a couple of weeks ago about the imago Dei as the "person-in-community," the theology of the image of God has social, moral and political implications.

“What I do in the privacy of my own bedroom is nobody’s business.”

This is such a common place idea that few today would challenge it. But they should. We should be talking about it. We should care what people do in their bedrooms. This idea that nobody should care what kind of sex you engage in as long as it is done in private and you are not exposing other people to it is a big part of why western culture and society is so messed up these days. It is at the heart of the culture war. This idea is also deeply wrong.

For many, this idea that our bedrooms are a sacrosanct place, that what we do there is our business and our business alone is foundational for many people in how they conceive of liberty. This understanding of morality assumes that we are, as human beings, all fully autonomous individuals, monads who are morally and spiritually isolated from each other. There is nothing that binds us together with other human beings. We have no unseen or “spiritual” bond with anyone else. This includes our neighbours. There is nothing “metaphysical” that connects me to my fellow citizens. This is the philosophy of nominalism at work, affecting the moral life and decisions people make.

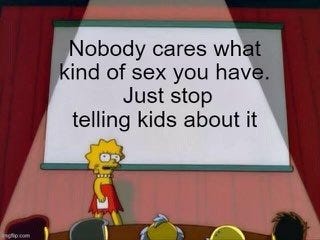

This way of understanding the world is individualistic. It sees the individual as primary. Any bond that a person might make is completely and fully voluntary and does not go any deeper than our consent. True to the philosophy of nominalism, any bond that I might feel with another person, is fully and completely the product of my feelings, my emotional state and nothing else. Any and all relationships remain always fully voluntary and I can enter into them and withdraw from them, retaining the full integrity of my self. At all times I maintain the integrity of my individual self. My actions are uniquely my own. I can choose to enter into a relationship or withdraw from a relationship. I can choose to give my consent or withdraw my consent. As long as I don’t try to harm you, to damage your integrity of person, people can freely enter into and withdraw from relationship as they see fit. As long as everyone consents to the actions that happen between people and no one harms the other, these actions remain ours and no one has the right to stop me because my actions as a unique monad have no effect on you as a unique monad, especially if you were not party to the action. What happens between two consenting adults is their business and affects no one else. Privacy ensures that my actions do not affect you at all. This meme captures the essence of it. As long as you protect others from your freely entered into actions behind a wall of privacy, then there is no possibility of your actions harming me or anyone else. After all, the argument goes, we are distinct, discrete beings, unique monads with no connections to any other persons. If we do what we do in private, these actions do not affect you and thus should not concern you at all.

This understanding of humanity and morality privileges consent. The only real moral questions that arise are those of consent and harm. At what age can someone consent to an action? If their actions only affect themselves, and they are freely consenting, then you have no moral say over what they do. Does someone have the capacity to understand the consequences of their actions? Are they mentally and emotionally able to consent? Are they able to freely consent? Were they under pressure or duress? Were they forced to do something against their will? This complex of questions becomes the only moral standard. This is also true of life and death. I should be able to freely choose whether to live or die. If I choose to let you kill me, this is my choice. You cannot make me accept any unchosen bonds. I should not have to enter into a relationship with the baby growing inside of me if I choose not to enter into that relationship.

This way of thinking is familiar to most of us. But it is horribly wrong and messed up. It really is anti-civilizational. This way of thinking is a denial, though, of much of how we experience the world. It is a denial that we have any collective life with other human beings. We are islands. We are ships passing in the night. This renders the idea of a shared culture an impossibility. How can you share anything with anyone else, let alone a culture, if there is nothing that connects you as human beings. When every relationship is a voluntary and transactional engagement between two distinct and discrete monads, there can be no bond between them, no unspoken connection, no metaphysical reality in which they both share.

Even though many of us make these arguments, most of us know intuitively that this is not the case. We develop bonds with our friends, to the point where we can finish each other’s sentences. We connect with people. Marriage is best example. It really is true with marriage that the two become one, especially the farther along you go and the more that you deepen that bond between each other. Families have a unique character, a connection that is based on genetics as well as the life they live together. Stable communities are the same. Churches. Clubs. Neighbourhoods. Towns and villages. They develop bonds that are unseen, intangible, spiritual even, but nonetheless real. How is it that we can recognize cultural differences between people groups, unless there are real shared commonalities?

This idea that people are morally autonomous and discrete entities unconnected to other people is a relatively new innovation. It is at the heart of much of the “fungible cog” way of thinking about mass immigration. People are bonded to each other and they are bonded together as groups. These groups have a shared identity, a personality of their own that is then reflected in the individual persons who make up the group. This is why I talked recently about the basic social unit not as the individual but rather as the “person-in-community.” Throughout most of human history this was seen as completely normal. Of course we shared a connection as human beings. Of course groups of people had their own personality and character.

Theologically, much of Christian teaching requires this idea of a shared “human nature.” This is the idea that we are bound together as human beings at a metaphysical level. We are made in the image of God. We are different from the animals. This image bearing quality is something that is expressed in some combination of our genetic makeup and the unseen spiritual aspect of our being, our spirit or our soul. When we connect with people, we are tapping into that thing that binds us together. There are the aspects that can be named, physical characteristics, personality traits, that sort of thing, but there are also those aspects that cannot be named, those parts that are uniquely ours. It is such a treasure when someone is able to see us, see into us, really grasp that ineffable part of who we are. We can connect wordlessly and we can connect with words. It is our common humanity, I believe, that allows us to connect in this way. Additionally, human sinfulness spreads and touches all of us because we all share in the same metaphysical human nature. Conversely, the salvation of Christ spreads through this same human nature. Christ, by redeeming our human nature, enables all of us to participate in salvation. Christian teaching must reject nominalism and with it the nominalist understanding of the person as a discrete monad.

Back to morality. Think about it. In marriage, if a husband is, in the privacy of his own room, is looking at pornography, this is not a discrete and private choice that has no influence on his wife and children. It is a betrayal of the bond he has with his wife. It corrupts and distorts their marriage relationship. In the same way, because of our shared human nature, the things we do in private affect the shared collective life of the people. We are like a single body. If one part of the body is sick, the whole body is sick. When people engage in deviant, immoral, or degenerate sexual practices, even when done consensually, they corrupt the whole of society, the collective life of the people. They make the society increasingly sick and degenerate. And it is not just sex. The whole range of what we would call sinful behaviours affect the whole of the body politic.

So, it should matter to you, what is happening in people’s bedrooms. Their degeneracy is making you degenerate. At the very least, they are making it increasingly difficult for you to be virtuous. Their private pleasures and perversions prevent society from becoming fully virtuous. Think about the kind of society you want to live in. Do you want a society where people live alongside other people but have no connection to them? Do you want to live in a society where your next door neighbours are perverts? Do you want your kids to grow up next to people who are secretly degenerate? This is what social breakdown looks like. Living, healthy communities are in each other’s business and they police each other’s behaviour. Why? Because this is just what they do. This is foundational for community. I wrote about this a while back:

Real communities limit your choices. In a real community you don’t have a lot of privacy. Everyone knows and is in your business. In real communities there is authority. Someone imposes a morality on you. There is right and wrong. There is sin. When community breaks down, either the whole society begins to fall apart, or some entity will step in to fill the void to reestablish social order. You can coast along for a while on the stored up capital of previously vibrant communities, but eventually it catches up to a society. The sickness of doing what you want in the privacy of your own home spreads. It spreads because we are all connected. Pride parades and drag queen story hour and teachers grooming your children happens because we told ourselves it wasn’t our business what people did in their bedrooms. Immorality doesn’t stay private. It spreads and metastasizes. Then you wake up one day and its everywhere. It’s no longer private and no longer just in people’s bedrooms. Someone will eventually have to restore order if society is to continue, and in our modern society that entity is usually the state. Suddenly the state is in our business, watching us. The state is telling us what right and wrong is. Here is the thing. Someone will be watching you and someone will be labeling your private behaviours a sin. The nature of the sins may change. They might stop policing sex, but suddenly become very concerned about “hate speech” and recycling and the environment.

This is something we should all be thinking about these days as we watch society begin to decay and crumble around us. We should be meditating on our connection with our family, our spouse and our children, our connection with our neighbours. How would we want them to live? What kind of people do we want our kids growing up next to as neighbours? What kind of neighbours are we? We should be thinking about the reality that about 60% of young people feel serious loneliness. Why? They have no connection with their neighbours. They are being deprived of something that makes them human. The “price” one must pay for living in community and having deep bonds with one’s neighbours is that you lose much of your privacy. But this is a good thing. People should more or less know what we do in the privacy of our own bedrooms.

Sex is quite literally how we make children. Forget this at your own peril.

I intuitively knew that I cannot trust certain conservatives after they were outed as homosexuals. It doesn’t matter how conservative they are fiscally. You explained my (and many other’s) intuition. This article will be saved and reread.