A Deep Dive into Jacques Ellul's "Autopsy of Revolution" pt.3: The Causes and Conditions for Revolution

What forces within society create the conditions for revolution?

Jacques Ellul makes the rather bland and seemingly self-evident observation that all societies contain within them forces which compete and conflict with one another. Sometimes they lay hidden beneath the surface, sometimes they are out in the open. Sometimes they are mere potentialities. At other times, they seem a constant source of open tension. The social frictions which exist in society are often the source its vitality, the reason why it is dynamic and energetic. But, there must be a mechanism for resolving or releasing these frictions or they build up to the point where they explode. As long as there is a way to mediate disputes and an ability to absorb grievances, a revolution will not occur. In this regard, agitation may actually serve a useful social purpose: blowing off steam, releasing the pressure. But if there is no mechanism for alleviating tension, or if there is no balance, such that one side is heavily favored over the other, grievances will grow until revolution occurs.

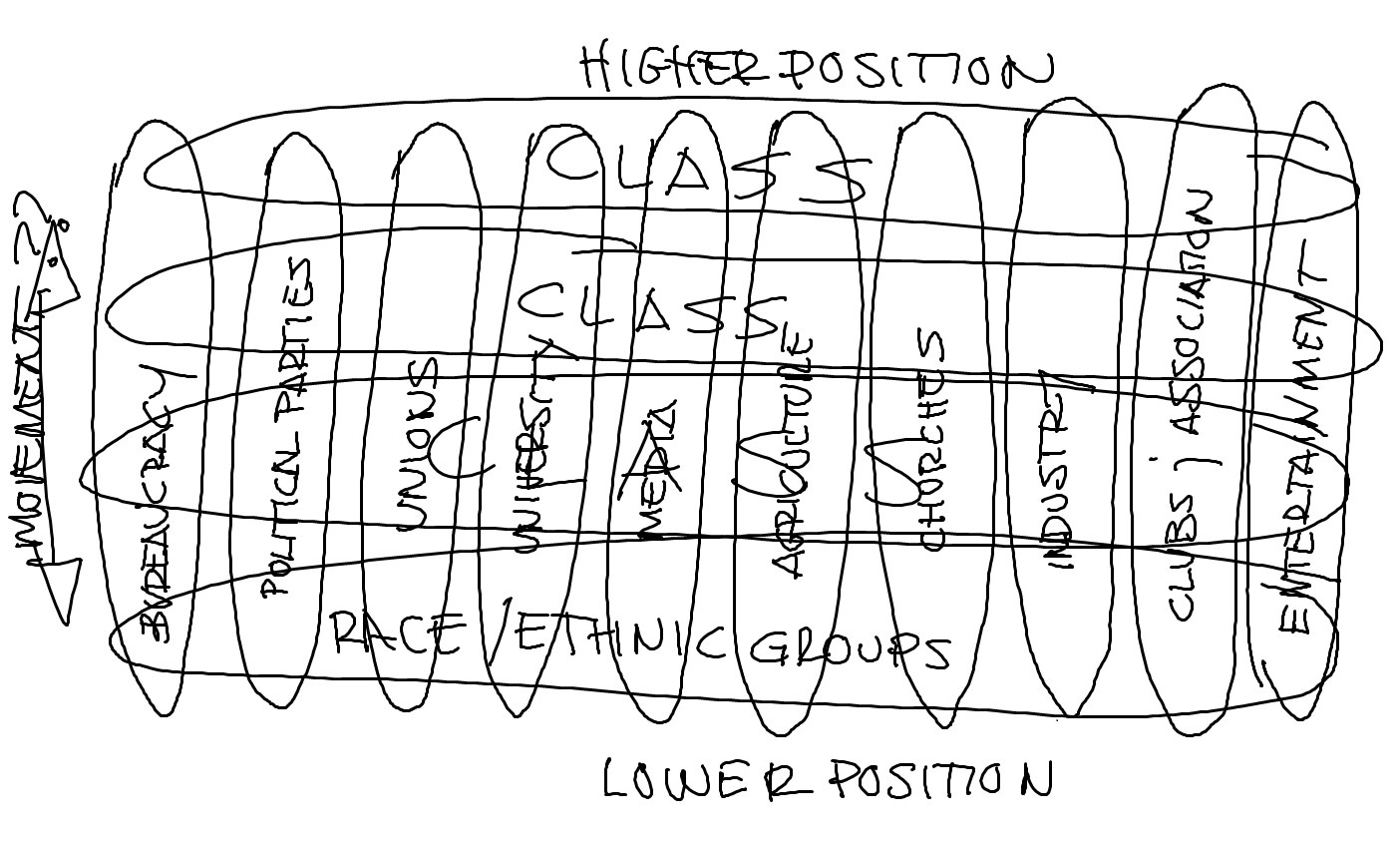

To examine this, Ellul uses Janne’s model as his base for understanding how these social tensions work and build up in society (my apologies to the reader, I thought I had the citation in my notes, but do not, and the book is now back to the university from which I borrowed it). People belong to various “horizontal” and “vertical” associations. Class associations tend to be horizontal. As are racial or ethnic associations. Various groups and institutions are vertical in nature. Basically, revolutionary pressure comes when the upper horizontal group comes to completely dominate the upper reaches of all, or the majority of the vertical groupings. I made this rough diagram to help the reader visualize this:

Looking at the diagram, you can see the various vertical groupings. They include areas of society like the bureaucracy, the political parties, the churches, unions, universities, media, industry, clubs, and even things like farming and so forth. These individual groupings, when functioning properly, allow movement up the social hierarchy. They also allow people to feel like they have influence upon the direction of society. They allow a means for both social movement, but also social integration. These groups allow people to move up, but they also force those at the top of society to grapple with and confront the concerns of people lower down the social scale, those who are in a different class.

If the upper classes, for example, stop going to church regularly, they no longer meet the factory worker in the same church. This means they are no longer rubbing elbows with on committees together or engaged in shared charitable projects with each other. There is no contact. There is no exchange. There is not understanding. The classes become remote from each other. In a different way, if the upper reaches of society come to dominate many of the key institutions in society, effectively locking out the other classes, races or ethnic groups, this will cause tensions to build up as these other horizontal groups feel shut out and cut off. The lower groups no longer have any means to rise socially or to have their voices heard. The degree to which the vertical groupings can mediate between the horizontal groupings is the measure of how successfully a society will be able to absorb, integrate and alleviate revolutionary pressures. Conversely, societies in which stratification is tightly integrated horizontally with little vertical movement or integration, is a society which will feel more revolutionary pressure.

Ellul then notes, that if the pressure builds up horizontally mostly in the middle class, then the revolutionary drive is more likely to lead to a fascist type revolution. If the pressure builds up most in the in the masses, the working class, the working poor and the underclass, this typically leads to a communist or socialist style revolution. As an aside, Ellul notes that a peasant or farmers revolt is really only a problem in a pre-industrial society. You will note in the above diagram that agriculture is a force for vertical integration in a post-industrial society. Farmers and rural folk in general no longer form a meaningful horizontal class according to Ellul.

The implications of this insight is that the conditions for revolution are not going to come from rural America, nor will the pursuit of trad living foster the conditions necessary for overthrowing the regime. In large part, whether they realize it consciously or not, Red America as a Heartland, rural and semi-rural group, exists not as a place where revolution will be fostered; but rather as the one of the few places where vertical movement and integration is still possible. Thus, the move to Red America and the “Great Sort” according to this schema, actually helps the regime by releasing the revolutionary pressures building up in Blue America, venting them to the Heartland. The feeling that you can return to flyover country and build a future for yourself is a positive for the regime. It is counterintuitive according to current thinking. But actually, if you want to rid yourself of the regime through a new revolution, you want people stuck in Blue America feeling like they have been locked out and they have no future such that their only option is revolution. The “Great Sort” is actually helping the Democrats retain power.

Ellul then notes that when these tensions build up within society, if they are resolved vertically, this generally manifests itself in a coup d'état. Essentially, what happens is that in one key vertical node, those locked outside of the upper reaches of power eliminate those above them and as a result are able to exercise enough horizontal force or influence that the rest of the ruling class falls in line. The classic example is the captains and colonels replacing the generals in a military coup. Revolution, then, occurs when there is a broad struggle of one horizontal group to replace the ruling group above them. Again, these struggles, both vertical and horizontal are always occurring. If they can be resolved peacefully through movement and integration, revolution can be avoided.

Conflict itself, though, is not enough. The final element needed is a consciousness within the lower horizontal group that they have been shut out, that vertical movement and integration is no longer possible. They need to know they have been displaced. In a sense, for a new revolution to take place in America, the “American Dream” must first die. Ellul notes, that if enough avenues of vertical integration can be found, this can lead to positive change. Reform will happen instead of revolution. If the upper class relents and opens avenues for movement and integration, these positive reforms allow release of the revolutionary pressure.

As useful as this model is, argues Ellul, in the end, it is still not fully sufficient for understanding the passions associated with revolutions. People use terms like the “industrial revolution,” talking about the radical alteration of social and economic structures, but then want to completely ignore in their understanding of the revolutionary phenomenon the role of violence. He argues that without violence, a revolution is not really all that revolutionary. Radical change is not enough. People want everything now a days to be “revolutionary.” But we dilute and empty the concept and fail to understand the true historical reality if we fail to include the necessity of violence to the reality of an actual revolution. Mere social change is not enough, no matter how radical or quick. For a revolution to be a revolution, the change must be violent, meaning an outburst of physical violence is central to the revolutionary event.

But for revolution to be possible at all, though, you already must have in place a certain conception of society and social order.

“There was a threshold, on the one side of which it was not possible to conceive of revolution; then at a particular time, it became possible to talk about revolution, to try to define it and analyze its specificity, something unimaginable in prior times.”

Revolts and rebellions have happened throughout history. What is new is the possibility of revolution, as talked about in the first piece of this deep dive series:

Two conditions, argues Ellul, produced this change in society which allowed the emergence of the concept and possibility of revolution:

“Awareness of social injustice and the realization that society was not inviolate.”

It seems a simple thing that we take for granted today, but it represents a remarkable transformation of our mental imagery. There was a time when man just endured injustice as part of his “lot in life.” What could you do to change one’s lot? The social order was simply what was. It was the hierarchy of being. Man could revolt, but the very idea of remaking the whole social order, by instituting a new rational plan for a better social order was simply unthinkable. And so, the idea of revolution was unthinkable.

Men had to come to see that the social order was not a metaphysical constant, the structure of reality which formed all things. Rather, they needed a change in thinking, that they as human beings could change and form their own order. Society could be built on human choice. If society could be build through the exercise of human choice, we could choose to sweep aside the existing order. You had to come to believe that there was no real metaphysical fixedness to this order. It was merely the result of a series of social choices made by other men. Their choices could be rejected in favor of our own new decision to build society in a new direction. The social order was not a thing of the Forms. In order for the social order to be changed, it had to cease to be seen as a sacred order.

When neither men nor their privileges are sacred, they can be contended with. When society and its order is no longer sacred, it can be reshaped by the will of men. Inequality and injustice are not a feature of an immutable social order that then must be endured because they cannot be changed; rather, they are merely the work of men that can be addressed by human action and eliminated from society. Before a man could condemn injustice, he had to see that his situation was unjust. If the order is natural and sacred one does not challenge this order, nor does one even see it as unjust. It is just what is. Ellul argues that it is only when human being are abstracted from the social order, and not an integral part of a grand cosmic order, that a revolutionary consciousness is possible.

When the social order was the source of meaning for your life, giving you your place in the hierarchy of being, providing meaning, safety, stability, order, how could one challenge this? How could a sacred order be called unjust? Only when this order is cast aside, can one even think of challenging the idea that one’s place in society is not inviolable. It can be changed. I can challenge my place in society.

In order to conceive of having a new model for society, to develop the revolutionary plan, one must have the idea that such a thing is even possible. At the same time, the theory of revolutionary action is dependent upon you being able to develop a rational, organized and successful revolution. The two phenomena are linked. Revolutionary theory is only possible when the reality of revolution is a possibility. We tend to want to project this idea across history as a grand theory of everything, as did Marx, but models of revolutionary theory are only possible after revolution has take place.

We have to separate revolts, coups, civil wars and other regime changes across history from the idea and reality of “the revolution” when the historical, social, technical and even metaphysical understanding of the world made a true revolution impossible. Nor should we project the idea of a “class struggle” onto other eras of history or other cultures. There is no grand unifying idea of “history” according to Ellul. Revolution is a decidedly western phenomenon that was birthed by the rise of the bourgeoisie in Europe and in the New World, announcing its reality and possibility in the French and American Revolutions. The ways of thinking that would have us produce grand unifying theories of revolutionary history and change throughout history are a product of the same changes which brought about the idea and reality of the revolution in the West. Revolution is a western thing born during the Enlightenment. In this sense, he argues, no general theory or definition is possible for “The Revolution.” It is a product of a particular culture in a particular time. If revolutions occur elsewhere, it is a sign of Western influence upon other cultures, their adoption of western attitudes and ways of thinking. Ellul argues that it is a myth to see, as Marx did, revolution as the central driver of all of history. “The Revolution” is a part of the modern Western culture and must be grappled with as a feature of our culture, but nothing more. It is very likely that when the West passes away, so too with it will go the idea and reality of revolution.

Very nice post. You wrote, "Revolution is a western thing born during the Enlightenment." Yes! This is exactly true; revolution as commonly understood in the West means revolt against the established order in order to institute an *even more* egalitarian government, which is metaphysically rooted in Pauline Christianity's "the first shall be last and the last shall be first". As Tom Holland states so eloquently:

"Fascism, I think, was the most radical revolutionary movement that Europe has seen since the age of Constantine. Because unlike the French Revolution, unlike and the Russian Revolution, it doesn’t even target institutional Christianity: it targets the moral/ethical fundamentals of Christianity. The French Revolution, the Russian Revolution are still preaching the idea that the victim should be raised up from the dust and that the oppressor should be humbled into the dust; it’s still preaching the idea that the first should be last and the last should be first just as Christ has done.

The Nazis do not buy into that. The Nazis buy into the Nietzschean idea that the weak are weak and should be treated as weak, as contemptible, as something to be crushed….

Atheists of today [like Richard Dawkins et al]… they are basically Christians. Nietzsche saw humanists, communists, liberals—people who may define themselves against Christianity—as being absolutely in the fundamentals Christian, and I think he is right about that because I think that in a sense atheism doesn’t repudiate the kind of ethics and the morals and the values of Christianity."

From: https://neofeudalreview.substack.com/p/the-egalitarian-ratchet-effect-why

🗨 political unity only happens at the expense of the ambitions of its constituents. It is only ever justified by the presence of some even more pressing external need. In the absence of an outside threat, the tendency for all internal suborders is to push apart and cannibalize the political commons for their particular gain.

Social mimics natural ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

🗨 A diversity of powers is necessary for life to survive the inevitable rise and fall of particular powers. Full unification is not only impossible; it would be deeply dangerous to the future of life.

palladiummag.com/2022/09/08/the-rise-of-the-garden-empires