A Deep Dive into Jacques Ellul's "Autopsy of Revolution" pt. 1: Revolt and Revolution

What is the difference between a revolt and a revolution? How does a revolt become a revolution and why it is vital for our current moment to understand how this happens and what it means.

I can't believe the news today

Oh, I can't close my eyes and make it go awayHow long, how long must we sing this song?

How long? How long?'Cause tonight

We can be as one

TonightBroken bottles under children's feet

Bodies strewn across the dead-end street

But I won't heed the battle call

It puts my back up, puts my back up against the wallSunday, Bloody Sunday

Sunday, Bloody Sunday

Sunday, Bloody Sunday

Sunday, Bloody Sunday

Alright, let's goAnd the battle's just begun

There's many lost, but tell me who has won?

The trenches dug within our hearts

And mothers, children, brothers, sisters torn apartSunday, Bloody Sunday

Sunday, Bloody SundayHow long, how long must we sing this song?

How long? How long?

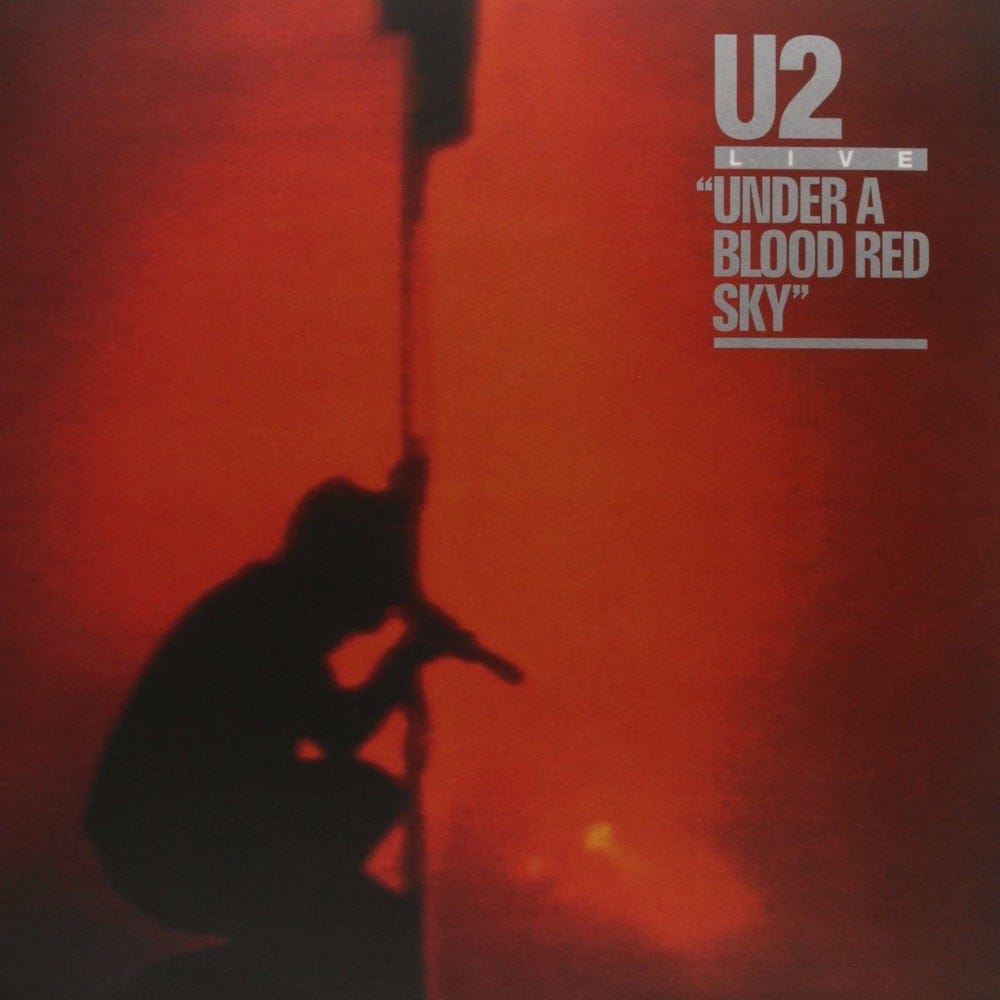

That was the first two stanzas of U2’s “Sunday, Bloody Sunday.” For me, I first heard the song when I was 17, after the 1983 live album “Under a Blood Red Sky” came out. It is still one of my all time favorites. It had a raw energy. It commemorated the Bogside Massacre of 26 unarmed civilians at the hands of British soldiers on January 30, 1972, many of whom were fleeing or helping the wounded. All were Irish Catholics. It was seen as an event symbolic of an intolerable English rule over the Irish people. The massacre was a pointed accusation against what was seen as an unjust and oppressive occupation. The song asks the question, again and again, “How long?”

In the opening of Jacques Ellul’s “Autopsy of Revolution,” he begins his book long examination of the nature, characteristics and development of the idea, history and sociology of revolution by observing that there are two enduring features of every historical revolt: the sense of the intolerable and the accusation of injustice and/or oppression. The rebel has reached the point where he cannot take it any longer. His limit has been reached. It is not necessarily a matter of any principles or concepts or even ideology. Rebellions occur because people feel they cannot go on living the way things are. The current situation must come to an end.

The rebel is fighting for the integrity of his being, for himself and his life. History cannot continue anymore along its current path. I talked recently about the idea of “history” in a recent piece:

A revolt, argues Ellul, is anchored to the idea of “History,” not in its acceptance or formation. The rebel is not making “history.” Rather, the rebel is rejecting “history.” The rebel is saying “enough is enough.”

Ellul draws our attention to the idea that rebellion is deeply related to an older idea of freedom, one that seems almost alien to us today. We generally look at freedom as the ability to make choices without any limits or restrictions. No one should be able to impose upon us any unchosen restraints, bonds or attachments. Ellul draws our attention to an older idea of freedom, as release from the intolerable and unbearable situation.

“Prior to the eighteenth century, freedom had another significance, a directly human one: escape from the unbearable, from the design of destiny whose immediate fact was the oppressor.”

To me this resonates well with a Biblical understanding of the freedom which God’s saving grace brings to us. The freedom of grace is a release from bondage and oppression to the devil and to our own sinful nature. Human sinfulness and bondage to the evil one is humanity’s intolerable, unbearable situation. The sacrifice of God brings release and sets the prisoners free. You are given a new beginning under the rule of new and better King. A passage like this from Paul’s letter to the Galatians makes much more sense if we understand freedom in this way.

“It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery.” Galatians 5:1

And it makes the framing of Jesus’ commission of Paul on the road to Damascus more understandable:

“ ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting,’ the Lord replied. 16 ‘Now get up and stand on your feet. I have appeared to you to appoint you as a servant and as a witness of what you have seen and will see of me. 17 I will rescue you from your own people and from the Gentiles. I am sending you to them 18 to open their eyes and turn them from darkness to light, and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me.’” Acts 26:15b-18

The act of salvation is a liberation from the cruel and unjust rule of Satan. You are set free from the intolerable and unbearable oppression of the devil, and are brought under the benevolent rule of God in Christ.

This understanding of freedom also informs the ideas contained in the Declaration of Independence which formalized the rebellion of the colonies against the British Empire. The language is clearly that of the intolerable situation which induces a people to act:

“But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government.”

Having laid the ground work, establishing the basic idea of the “revolt,” he then begins to delineate the difference between a “revolt” and a “revolution.” Ellul argues that a revolution is always constructive, in that it builds towards the future. The revolution wants to put in place a better tomorrow. A revolt, on the other hand is always an “earth-rending upheaval in the face of an unknowable future.” Essentially, what separates a revolt from a revolution is that a revolution has a plan for the future. A revolt does not lead anywhere.

“Even when a revolt succeeds temporarily, it does not know what to do with victory.”

It is not winning a revolt that makes a revolt into a revolution. A nomad can invade the city and conquer it, but not have any clue what to do next. So he takes his spoils and returns back to the wilderness from whence he came. The rebel does not know how to create history. The rebellion is a refusal, a rejection of the current trajectory of history. Thus, asks Ellul, what would Spartacus have done with Rome as the leader of a rebellious band of slaves? After winning his victory, he retreats from power, from the necessity of organizing a society and the order he should have established.

Thus, a rebellion is the willingness to embrace death as more tolerable than the current situation. It is the grasping of freedom, even if it means his own death and the death of his his society. The rebel is willing to tear it all down for blessed release from the current moment. There is nothing beyond victory. The rebel only moves toward death.

Understanding this, we must ask, has the current situation reached the point where things are so intolerable that death is the best viable alternative to things staying the same? There is still a lot of excess in the system. People complain a lot, but on the whole life is still ok. At what point, though, with the current regime, will that situation change?

One of the challenges faced in resisting the current regime, is its size, ubiquity and abstract nature. Additionally, much of the thinking which occurs in regards to the regime, and what to do about it, is itself abstract and theoretical in nature. Ellul says this:

“For revolt to occur, there must be a clear and distinct identification of an enemy, of someone responsible for the general misfortune.”

It has been often observed about the administrative state, in whatever form you find it, whether in government, business, universities, or non-profits, that it almost always seems to be the case that no one is in charge and that no one is responsible for anything which goes wrong. All problems are systemic and technical in nature. There is no face to the regime. Everyone knows that Joe Biden, for example, is not in charge of anything. So who is? For a revolt to occur you need to put a face on the suffering of the people. There must be a clear, identifiable enemy. Someone must be responsible for the current misfortunes of the people.

At the same time, once these pressures begin to build up in society, they cannot be appeased by sociological analysis or by abstract ideas. You cannot hold an abstraction like a “class” responsible. Nor can you hold “the state” responsible for the problems of the people. Even figures removed from the lives of the people like a king or a president do not make sufficient objects for which to channel the anger of the people.

“The enemy, the source of his grief, is bound to be at hand, within striking distance.”

What is needed is a real scapegoat, in the Girrardian sense, who must be sacrificed to appease the people, someone or something concrete which can then suffer for the sins committed against the people. This is what makes resisting the technocratic administrative state so difficult. Responsibility is masked by “org charts” and policy manuals. There are hundreds and hundreds of nodes which disperse responsibility for the current state of things.

Ellul also argues that it is a mistake to look at the current situation through the lens of the class conflict or some other sociological analysis which cleanly and neatly pits one group against another clearly defined group. If you look at rebellions historically, they are typically made up of a cross section of society, pulling people from groups which sociological analysis informs us should feel great antipathy towards one another. He underscores that the idea of a class is an abstraction. No one rebels against an abstraction. Rebel groups unite together from across society, to vent their anger against a clear identifiable enemy which can fixed upon, readily identified and is close at hand, within striking distance.

“The notion that revolutions have a social origin is a pure and simple assumption fostered by Marxism. It is historically incorrect.”

And we are farther from revolt or revolution than we might think.

“When a group comes to recognize the specificity of its values, when the commonly accepted values disintegrate, then there is a situation which normally produces a revolution.”

We all sense the growing disintegration of the existing values of society. At the same time, many are looking to solve the current crisis by trying to revive earlier forms of these values. We need to purify the values. Especially in the core of the empire, in America itself, most feel the need to attach their dissent in some form or another to “Americanism.” The values have not disintegrated to the point where people are looking for true fresh start. People want a renewed America. They want something that is recognizably “American.” Not too many are really so dissatisfied that they are looking to hit the reset button on the whole project.

Additionally, what would people cling to as a shared value set. While the progressive regime seems to have a clear understanding of its project, those who are in opposition are all over the map. Neo-cons. Normie-cons. Washington establishment conservatives. MAGA-boomer-cons. The new right, whatever that is. The dissident right and its multitude of factions. Catholic integralists. Common good conservatism. Christian nationalists. I certainly don’t see in this mess a group that has come to “recognize the specificity of its values.” We neither have the disintegration necessary, nor the emergence of a vital alternative to create the conditions necessary to foster the kind of revolt that may lead to revolution.

We must remember that a revolt is an “embodied” happening. It is the encounter between a real situation and a specific occasion in which men put their bodies on the line in a real way that produces the revolt. It’s the decision to die boldly rather than continue on.

The Revolt Against History

Ellul argues that the idea and praxis of revolution is a modern phenomenon. It is not until modernity that both the spirit and necessity of engaging in revolutions becomes a reality. The French and American Revolutions mark a historical demarcation period, after which we must now think in terms, not merely of revolt, but now in terms of revolution. A revolt is a spontaneous act. A revolution is thing of rationality.

The revolution frequently grows out of a revolt, but is a different thing than the revolt. The revolution that emerges in the wake of the revolt will take the character of the revolt and will be shaped by its energies. Revolutions are not spontaneous, though, although they often graft themselves onto spontaneous movements. The upheaval of the revolt allows the revolution to take place. Without this upheaval, revolution is an impossibility.

The early revolutions, prior to Hegel and Marx, bore a similarity and an affinity with the revolt. Both were directed against the perceived flow of history. Revolution is opposed to what can be achieved through a gradual evolution of society and events. Revolution, like revolt, was a refusal to advance towards the future laid out by the status quo.

“The celebrated Marxist formula: ‘revolutions are the locomotives of history’ is a gross misstatement of fact. On the contrary, they usually seek to impede the movement of history.”

Over the long history of revolts and into the revolutionary period, people engaging in both were not looking for innovation. They were not looking to advance progress. They were generally revolts against the “progress” of the ruling regime. Prior to the 19th century, most revolutions were reactionary. They are a refusal to continue in the present course of history. They were reactions against innovation, excess and change.

“Most revolutions prior to the 19th century had a double thrust: they were conservative, even reactionary, bent on maintaining a situation and, better still, on restoring a former one, real or imagined. Or they represented the determination to obstruct a ‘normal’ predictable future, evaluated in terms of the present.”

The revolution was perceived to be a way back, a rebellion against the movement of history in the making by the current regime. Rebellion was a search for a way back to the past. The revolt and revolution expressed a desire to start over. A fresh beginning. The early revolutionaries were not looking to “make history” but were instead, rejecting the current trend lines of historical movement. You can see this impulse at play in the American Revolution and the desire to draw on the first principles of natural law, to ground their society in something older and deeper than the current British regime.

From Revolt to Revolution

So how does a revolt become a revolution? The revolution begins with revolt and emerges from it. Revolt, as we noted is a kind of void, a visceral, physical explosion without thought. A revolution requires a doctrine, a plan, a program. It is undergirded by a theory of some kind. A revolution has an intellectual force behind it that the revolt does not. The revolution is a revolt that seeks to institutionalize itself.

“What characterizes the transformation of revolt into revolution is the attempt to provide a new organization.”

You can have a revolt without planners and managers, but to make a revolution happen, you will need managers and institution builders. This is, in large part, why revolutions are a thing of the modern world. They require a large cohort of technically inclined mangers who are adept at turning energy and ideas into policy and institutions. To make a successful revolution happen, you need a combination of rebels and managers. You need people who can tear down. And you need people who can build something up. After the storm of the revolt has exhausted itself, you need people who can put things in order again.

All revolutions require ideas. They begin with a concrete ideology, a plan for how a new future can be built after the current intolerable situation has been swept away. Revolution is not an attempt at reform. It does not desire to work with the existing institutions or the current system. Reform is not part of the revolutionary event. It is always a fresh start, a desire to hit the resent button and begin again with a new set of institutions. History has become unbearable and we need to start over again. A revolution establishes a beginning.

A revolution ties itself to the idea of freedom, because, as we have seen, this beginning comes out of the release from the current oppressive situation.

“He is set free by being placed at this beginning.”

The revolution has a dual purpose of trying to establish a new beginning while honoring the spirit of the revolt to retrieve the better past before the depredations of history made history intolerable. Ellul argues that the plan for this new beginning inspires, evokes and stimulates the imagination and arises from the yearning of the soul of the people. The revolution is a kind of cult object, an idol, a holy thing, worshiped and honored before it is set in motion. Revolts are shot through with the black humor of the gallows. They can be joyous celebrations, exultant. Revolutions, on the other hand, are serious, solemn, sacred: a religious rite.

Because a revolution, at its essence, is a plan for a new beginning, there can be no spontaneity in a revolution. It is always initiated with forethought and intention. A revolution is aspirational. Whereas, the focus of the revolt must be tangible, identifiable and close at hand, the revolution is the formation of a broad doctrine. The revolution requires an adversary that is sufficiently universal to remake the entirety of society.

It is this universalizing, planned, managerial nature of the revolution that requires the instantiation of the idea of the modern state in order to realize itself. The state becomes the instrument, the medium, for transforming a revolt into a revolution. The revolution implies an orientation towards organization and institutionalization. Ellul argues that this is essential for understanding the essence of the revolution. He gives the example of the American situation with its new constitution and the establishment of the institutions necessary to instantiate the revolt and make it a viable revolution:

“…concern for institutionalizing freedom was in the American Revolution, the objective of which was to consolidate in a constitution the power born of the revolution. Then and there the organizer emerged as the central figure—the one through whom the revolution fulfills its meaning.”

But there is a catch-22 situation. The revolution is born out of the revolt of the people, their throwing off of the current intolerable order in order to claim their freedom. But, lest the whole thing is allowed to die out, as all revolts inevitably do, the revolution must put an end to this destructive embrace of freedom. It must build something stable and solid. The revolution must put an end to the revolt, and even to the revolution itself.

“Revolution cannot escape the transition to institutions and managerial control. The managers frequently have absorbed, if not created, the doctrine. They are forever accused of being exploiters and betrayers of the revolution; in actual fact, if they had not been on the scene, the revolutionary stage would never have been reached.”

You must embrace the idea that the success of a revolution requires its betrayal by the managers. The ideas that drove the revolutionary spirit, that allowed the revolution to escape the destructive excess of the revolt, once put in place by the managers and instantiated into institutions at the same time both realizes the revolution and betrays it. The freedom experienced in the rush of the revolution is circumscribed and closed off by the newly created institutions which were put in place to secure and realize that same freedom. Once the Constitution was put in place and the institutions it specified were made a reality, the revolution both simultaneously was successful and yet that same success was betrayed by the same new institutions. There is no way around this catch-22, this fundamental revolutionary contradiction, argues Ellul.

Revolutions are not made by leaders and agitators. They require organizers and managers. The revolt becomes revolution the moment the task of construction begins.

“Revolt is itself the liberating movement. Revolution seeks to organize the situation, to find a stable construct for freedom.”

Revolt is movement. Revolution is the re-establishment of stability. The revolution, to be what it is, is always destined to create a new regime or a new political body. It begins the process all over again. Revolution is the movement from agitation to integration, from fighting to governing. The failure of the revolution to emerge from the revolt will likely mean some form of mass death and destruction and the impulse to tear down will continue to feed itself. It may mean the emergence of some greater tyranny than the one just overthrown if the revolt cannot establish itself in revolution. In order for the revolution to succeed it must kill the spirit of the revolt in the transition. In order for revolt to succeed it must be institutionalized. But the process of doing this effectively ends the revolt and the great spiritual energy which drove it. Thus, there is always a hostility, a contradiction, between the revolt and the revolutionary gains. There is no revolution until the institutionalizing begins. The rebels are always convinced that they have been betrayed, but this betrayal, while real, is necessary for the success of the rebellion. To succeed the rebellion must become a revolution.

To put this into terms uniquely American, the freedoms that were fought for during the revolt against Britain, could not be realized unless they were first betrayed in the establishment of the new revolutionary government. In order for America to become America, the freedoms won at great cost during the revolutionary war had to be sacrificed so as to establish the forms of the new American state. The full nature of that betrayal may not have been fully felt or realized until some time later, but the decisive moment was the transition from revolt to revolution. People often argue whether the American ideals were betrayed in Reconstruction, or The New Deal or the Civil Rights Era. But in fact the first betrayal of the revolution occurred in the act of the Founding but this betray of the revolutionary spirit was necessary in order to institutionalize it and give it form.

Next: “Revolution Within History.”

This is a brilliant portrayal of Ellul’s insights and explains to me why the amorphous blob of organizations seem never to be held accountable personally. Without a definite head if the problem, the people cannot rally against it and focus their true grievances. I think this is in part why the Bud Light ad campaign with Dylan was so catastrophic for the company. They gave a definite figure (who has an uncanny valley appearance) for the masses to throw all of their pent up frustration about the militant trans movement coming for their culture and their children. This is also why drag queens at story hours at libraries make parents so incensed. There is a definite figure who is pushing for these campaigns to introduce trans to their kids. It’s very different than a parent walking into a library, seeing all the trans books in the kids section and not knowing clearly who put them there, which librarian or faceless bureaucrat in a state or local office made those books appear. Thank you for your great writings!

The tension between revolt and revolution is interesting as is the idea that the revolution is, largely, pre-planned and waiting. I don't see unity amongst the eRight, but I do have notes jotted down somewhere that for America the appeal needs to be uniquely American in ethos. Unfortunately much of the terminology to do so has been co-opted by gross misrepresentations and that presents a puzzle. How do you disentangle freedom from libertinism which is how it's largely understood today - for instance.